U.S. Supply Chains Disrupted by Millions Calling Out Sick

U.S. Supply Chains Disrupted by Millions Calling Out Sick

(Bloomberg Businessweek) -- Hundreds of workers at a Smithfield Foods Inc. meatpacking plant in Crete, Neb., contracted Covid-19 at the height of the pandemic last spring. For about 50 of the facility’s 2,300 employees, a fear of getting sick because of preexisting conditions has kept them from working ever since.

“We work so close together,” says a Smithfield worker in pork production who’s been on leave from the plant throughout the pandemic and asked not to be identified for fear of retaliation. “It’s like pulling teeth to find out if the person next to you tested positive.”

While the surge in the number of unemployed Americans has been a focus of economists throughout the pandemic, another problem in the labor market has been mostly overlooked: The people that do have jobs are calling out sick in record numbers or taking leaves of absence.

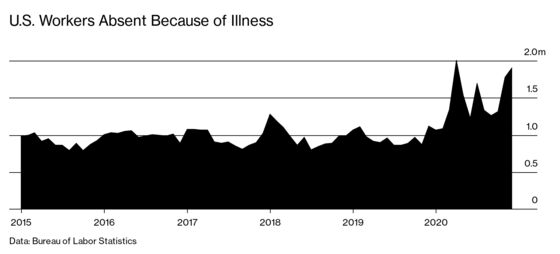

Unlike the jobless rate, which has declined markedly from the peak in April, the rate of absenteeism has remained stubbornly high. More than 1.9 million people missed work in December because of illness, according to Labor Department data, almost matching the 2 million record set in April and underscoring the impact of a third wave of coronavirus infections.

These lost days of work are sapping an economic recovery that’s been progressing in fits and starts for the past several months. Some indicators have improved significantly, but others such as retail sales and personal income have weakened as the pandemic rages and local governments impose fresh restrictions on businesses and travel.

Michael Gapen, chief U.S. economist at Barclays Plc, says vaccinations could start driving down absenteeism by the second quarter. Until then, the missed work is causing supply chain disruptions that may eventually show up in economic data. Absenteeism “could lead to shortages, it could lead to higher prices and more restrained output,” he says.

The problem is so acute that companies in industries ranging from meatpacking to consumer packaged goods are lobbying to get their workers near the front of the line for vaccinations. The Consumer Brands Association, which represents Clorox, Procter & Gamble, Kellogg, and others, says the absenteeism rate has been averaging 10% over the last two months, with some members reporting rates at high as 25%. “The challenge in keeping lines up and running, the challenge in continuing to meet the extraordinary demand that’s out there is absolutely enormous—and our companies are feeling it,” says Geoff Freeman, chief executive officer of the CBA. “There are instances of having to shut down lines at various points in time in order to manage the absenteeism.”

While U.S. Department of Labor data tracks people currently in the labor force who are out sick, a separate survey by the U.S. Census Bureau captures an even wider view. Its latest Household Pulse Survey—based on responses in December—estimates that more than 18 million people weren’t working because of the virus. The figure includes people who were sick as well as those who stayed home because they were worried about getting or spreading the virus, those caring for someone with symptoms, and those looking after children not in school.

The effects are especially concentrated in manufacturing. General Motors Co. put white-collar employees on the production floor in August to cope with labor shortages amid strong demand for cars and trucks. While safety protocols have prevented Covid-19 spread within GM plants in recent months, there’s no way to stop workers from getting infected outside the workplace, which presents an “ongoing challenge,” according to spokesperson Dan Flores.

The Institute for Supply Management’s gauge of factory activity increased in December, with the employment component returning to a level that indicates growth. Even so, survey respondents noted that Covid is affecting them “more strongly now than back in March.” One running complaint among survey respondents is that vendors are grappling with their own employee shortages, which is causing supply constraints. “The quantity of infections and the quantity of people who are having to self-quarantine or be sick is just so overwhelming that everybody has to be affected by it,” Timothy Fiore, chair of ISM’s Manufacturing Business Survey Committee, said on a Jan. 5 call with reporters.

For office workers, 90% of professionals said before the pandemic they’d sometimes go to work sick, according to a 2019 study by staffing firm Accountemps. Covid changed the conversation, and more employees are staying home to protect themselves and others.

The Families First Coronavirus Response Act that Congress enacted in March made the decision to stay home easier for some by allowing two weeks of paid sick leave for certain employees. The law also allows leave for those unable to work because they must care for a child.

The latest stimulus bill, signed by President Trump on Dec. 27, includes an extension of the act through March 31 but makes paid leave voluntary for employers rather than mandatory as it was in the first iteration. The act also excludes essential workers, meaning those employed at facilities such as meatpacking plants can’t take advantage of the policy. That in turn may lead to workplace outbreaks and further disrupt production this year.

“We know when the absenteeism will end, and that’s when we get the vaccine in people’s arms,” says Freeman of the CBA. But a patchwork of state-run vaccine rollouts and a lack of federal leadership means “this is the Wild West right now, and we see the results of that.” —With Michael Hirtzer and Julia Fanzeres

Read next: The U.S. Needs More Covid Testing, and Minnesota Has Found a Way

©2021 Bloomberg L.P.