Cost-Cutting at America’s Nursing Homes Made Covid-19 Even Worse

Cost-Cutting at America’s Nursing Homes Made Covid-19 Even Worse

(Bloomberg Businessweek) -- In early April the Trevecca Center for Rehabilitation & Healing in Nashville received an urgent call. At the time, Tennessee had only 3,000 coronavirus cases, compared with more than 100,000 in the state of New York. But the caller, the nursing director at a nearby kidney dialysis center, was worried. She said one of the home’s residents had been given a routine test before an appointment and had tested positive for the coronavirus. She said she believed that Trevecca, a 240-bed nursing home, might have an outbreak on its hands. Trevecca’s managers were busy, she was told, so she left a message.

Two days later, the caller tried again, insisting that this was serious and asking to speak with the home’s administrator, Carl Young. But she didn’t get through to Young—nor did people from a second dialysis center with an identical warning, say four current and former Trevecca employees familiar with the calls.

The dialysis workers weren’t the only ones worried that something was wrong at the facility. Nashville’s Metro Public Health Department had also gotten a report from a Trevecca contractor who was helping oversee its ventilator unit. The contractor said a Trevecca manager had warned him that sick residents weren’t being tested for Covid. “This just does not seem right clinically or ethically,” wrote the contractor in an email, which was first reported by the city’s NewsChannel 5.

Metro health officials spent several days trying unsuccessfully to reach Young. On Saturday, April 4, Michael Caldwell, the department’s director, drove to Trevecca’s five-story facility and left his card, imploring Young to get back to him immediately. That evening, Young finally did call, assuring Caldwell that everything was under control, according to health department officials. He said no residents were showing symptoms of the virus, and there was no need for tests. (Young didn’t respond to requests for comment.)

It would be another 18 days before health officials came in to test all of Trevecca’s patients and many of its workers. By the time that finally happened, on April 22, the disease had spread widely. More than 45 out of about 300 tests came back positive. In the coming weeks, more than 100 additional residents and staff would be infected. Six would die, including Charles Horton, an 82-year-old former police officer. He’d first showed symptoms, including shortness of breath, in mid-April.

The facility had previously told his son, Tim Horton, that his dad was negative for the virus. But Charles’s symptoms worsened, and he was rushed to the hospital in late April, where he tested positive. He died on May 2. Tim thinks if management had tested the entire building sooner, his dad might still be alive. “These people have shown neglect,” says Tim, who isn’t sure whether his dad was actually tested earlier. He’s hired an attorney to pursue a lawsuit against Trevecca’s owners. “It ain’t right.”

Trevecca is one of nine Tennessee nursing homes acquired over the past four years by CareRite Centers LLC, a chain based in Englewood Cliffs, N.J. In response to a detailed list of questions, Ashley Romano, CareRite’s chief experience officer, said in a written statement that the company has “worked diligently to go above and beyond what is recommended by regulatory bodies to ensure the health and safety of our residents and staff,” including setting up isolation zones, discontinuing communal dining and activities, and supplying protective equipment before it was required. Romano added that CareRite’s facilities, including Trevecca, passed infection-control inspections since the pandemic began. “Our company was founded by people who care deeply about our work and the residents and families we serve,” she said.

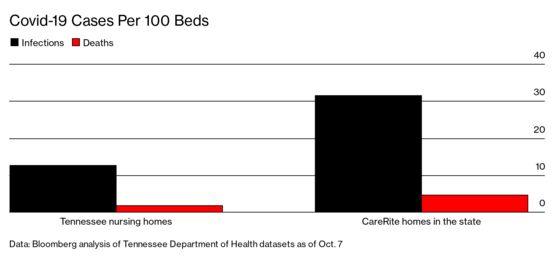

Two of Tennessee’s three largest outbreaks at nursing homes to date have been at CareRite homes, Trevecca and the nearby Gallatin Center for Rehabilitation & Healing, and two other CareRite facilities are among the top 15 in Covid cases statewide. As of early October, the company operated 4% of the state’s nursing home beds but accounted for 10% of cases and 11% of fatalities, or 71 deaths in total. The numbers are similarly elevated when compared with facilities around Nashville, a virus hot spot. CareRite’s five homes within 25 miles of the city center suffered an infection rate more than three times that of the metro area’s 26 other homes.

Romano says CareRite has detected a high number of cases because it proactively tested residents and staff “whether or not they are showing symptoms.” She adds: “These measures undoubtedly showcased higher numbers but most importantly allowed us to separate the sick from the well and celebrate countless recoveries.”

But many employees say these high infection rates were entirely predictable, caused by a lack of supplies and a blinkered attitude about the risks the virus posed. “It was a hot mess,” says Tika Johnson, a 45-year-old nurse practitioner who worked as a contractor at Trevecca and spent seven days in intensive care after testing positive on April 24. (She stopped working in CareRite homes not long after she recovered.) “They weren’t prepared for what was coming,” she says.

Outbreaks at nursing homes have become achingly familiar across the U.S., beginning with the one in February in Kirkland, Wash., that killed 35 elderly residents of the Life Care Center. Only 0.6% of the total U.S. population lives in nursing homes and assisted living facilities, but they account for 40% of Covid fatalities, according to data from the Kaiser Family Foundation. Put more simply: Residents of long-term-care facilities are about 100 times more likely to die from Covid than members of the general population. More than 450 nursing homes, out of 15,000 nationwide, have suffered outbreaks that infected 100 or more people.

As industry executives point out, some of the reasons for these high death rates have nothing to do with the homes themselves. Old people who become infected with the coronavirus are much more likely to die from it, and anyone who lives in close quarters with others is at greater risk of infection. “Unfortunately this virus does not discriminate,” said Richard Feifer, chief medical officer of Genesis Healthcare, the nation’s largest nursing home chain, in a May investor call. “It has impacted five-star and one-star centers alike.”

Early research led by David Grabowski of Harvard Medical School seemed to support the idea that nursing homes were powerless to stop outbreaks. Grabowski found no apparent correlation between facilities that became virus hot spots and those that scored low on traditional quality metrics, including past infection-control violations or whether the facility was owned by a for-profit business. Instead, he found, the two most critical factors were beyond any home’s control: a facility’s location (whether the surrounding community has a high rate of infection) and its size (the bigger the building, the larger the staff—and the higher the likelihood someone will carry the virus inside). “It’s much more about where you are and not who you are,” Grabowski said during an online seminar in May. “I don’t think this is a bad-apple problem. This is a system problem.”

The research gave the industry ammunition to argue that Covid deaths weren’t its responsibility. “It’s been said that blame is a person’s way of making sense of chaos,” wrote New York nursing home lobbyist Stephen Hanse in an op-ed in the Buffalo News in May. “Outbreaks of Covid-19 are not the result of inattentiveness or shortcomings in long-term care facilities.”

Meanwhile, some governors, such as New York’s Andrew Cuomo, may have erred when they sought to free up hospital space by requiring nursing homes to accept Covid patients who were medically stable. “Most homes weren’t prepared to manage these patients,” says Michael Wasserman, a geriatrician and, until recently, president of the California Association of Long Term Care Medicine. It’s not clear whether infected staff and residents, or these new patients, many of whom were likely no longer contagious, were the main vector for transmission inside the state’s nursing homes.

Even so, President Trump jumped to blame the scale of the outbreaks on missteps by Democratic governors. “11,000 people alone died in Nursing Homes because of [Cuomo’s] incompetence!” he tweeted on Sept. 3. Around the same time, the U.S. Department of Justice announced it was considering investigations into New York and three other Democratic-led states that issued similar directives. (Cuomo rescinded New York’s order in May.) Amid the political scrum, nursing homes have largely evaded responsibility. In fact, at least 26 states, including Tennessee, have granted nursing homes some level of immunity from Covid-related lawsuits.

But there are strong indications that nursing homes aren’t just blameless victims and that the industry has, by lobbying against stricter federal rules and cutting staff sizes, likely helped accelerate outbreaks. Last year, at the urging of industry groups, the White House proposed easing rules enacted by President Obama that would have required each facility to hire a dedicated infection prevention expert. Trump’s proposal received praise from the American Health Care Association, the main industry trade group that argued for it, and some homes postponed hiring these experts until the rules were finalized. “Failure to have this position fully implemented has proven to be a costly mistake,” says Debra Fey, an infection prevention nurse and consultant for the long-term-care industry.

Moreover, since Grabowski’s initial research was published, four more papers have found that certain quality metrics do matter in outbreaks. Yue Li, a professor at the University of Rochester Medical Center, for instance, examined data from nursing home infections in Connecticut through mid-April and compared the homes’ rate of infections to the number of registered nurses they employed. The industry tracks nursing staffing in terms of minutes worked by RNs, per resident per day. Li found that among homes with at least one infection, every 20 minutes of additional RN staffing time was associated with a 22% decrease in Covid cases. Charlene Harrington, of the University of California at San Francisco, found a similar link for homes in California. RNs are “the only ones really trained in infection control,” she says.

Of course, nurses are expensive, and CareRite, like many other large operators, has financial incentives to employ fewer of them. The company’s four facilities in Tennessee with more than 100 infections apiece averaged only 22 minutes of RN time per resident each day, about half the national average of 41 minutes, according to data compiled by the U.S. government for the fourth quarter of 2019. CareRite’s five other Tennessee facilities fared somewhat better, averaging 38 minutes of RN time and ranging from 25 to 61 infections each.

Meanwhile, nursing aides at CareRite facilities spent 14% fewer hours per resident per day, compared with other facilities in the country. That statistic could also be seen as troubling. A paper published by University of Chicago researchers in August found that higher numbers of hours worked by aides, who are responsible for changing, bathing, and feeding residents, correlated with a lower probability of an outbreak. “Having enough nurse aides to implement virus containment will be crucial if deaths are to be averted,” they wrote.

Grabowski, the Harvard professor whose research was touted by the industry, says he believes the new findings. Although he maintains that location is still the strongest predictor of an outbreak, “staffing does limit the size of an outbreak and the number of deaths.” He adds that though all nursing homes are susceptible to the virus, the industry glommed onto only certain parts of his initial findings. “Nothing we wrote said that nursing homes shouldn’t be accountable,” he says. “No one should get a get-out-of-jail-free card.”

Before CareRite came along, Trevecca and the nearby Bethany Center for Rehabilitation & Healing were owned by Emily Whitcomb, whose family had operated the two nursing homes since 1994. Whitcomb moved her own parents into Trevecca when they became too old to care for themselves. Her motto was “happy residents, happy employees, and stay in the black,” according to a former Trevecca manager who worked for both owners. “She believed that if you provided good patient care, profit would follow,” this person says. Whitcomb, who usually turned a modest profit at the homes, decided to sell them to CareRite in 2017 amid the chain’s statewide expansion.

CareRite was founded in 2011 by entrepreneurs Mark Friedman and Neal Einhorn, who had bigger ambitions. Starting with homes in New York, they built a national network that relied on polished marketing—early brochures promoted a “dynamic fusion of luxury and service”—and, at least in Tennessee, cost-cutting, according to interviews with 29 current and former employees at the CareRite homes in the state. After the company bought Whitcomb’s homes, it eliminated yearend bonuses of a few hundred dollars per employee. Orders for supplies were trimmed, sometimes leaving the buildings short on gloves and gowns. Nurses were occasionally told to tape together residents’ colostomy bags so they didn’t leak because they didn’t have the right sizes in stock, says Amanda Shannon, a supply manager who worked at Trevecca for four years before quitting in 2019. “We went from having everything we needed to having not enough,” she says.

As CareRite has expanded its business to include 29 homes in Florida, New Jersey, New York, and Tennessee, some attorneys specializing in cases of alleged nursing home neglect have become familiar with the company. “What we see over and over again is the lack of staffing and the lack of supplies,” says Cameron Jehl, an attorney in Memphis, who’s filed at least five lawsuits against CareRite in Tennessee, alleging that cutbacks contributed to residents’ health problems. One of his suits was filed on behalf of a woman at Bethany Center who developed bedsores and also fractured her hip in a fall last year. In legal filings, CareRite’s lawyers have denied allegations of substandard care.

After CareRite acquired Trevecca, employees say it slashed the budget to keep the facility clean, reducing spending on linens, towels, and blankets by more than 50%. Nurse’s aides sometimes had to cut old sheets into pieces to use them as washcloths for residents. Meanwhile, several housekeepers were laid off, often leaving one person to clean 30 rooms on a floor during an eight-hour shift, when before there’d been two. Workers say the building fell into disrepair. Blankets wore so thin that a staff member recalls holding one up and reading the time off a clock through it. The lobby was adorned with big potted plants and plush upholstered chairs, but the cream-colored carpet accumulated an ever-expanding collection of stains.

Few departments were as badly depleted as housekeeping. When residents are moved within a facility, a standard practice among nursing homes is to disinfect the rooms thoroughly, conducting what is known as a “terminal cleaning.” This includes spraying down the mattress, scrubbing the surfaces, and swapping out the privacy curtain. After Trevecca started turning up positive cases in late April, the home had to move dozens of residents around to create isolation units. Employees say that some of these moves happened without the disinfection process, potentially exposing healthy residents to the virus. “We didn’t have enough people to do it,” says Daisy Shipp, who worked as a housekeeper at Trevecca for 12 years before leaving in May. “Sometimes the mattresses wouldn’t get cleaned.”

Even though we now know the virus is spread mostly through the air rather than on surfaces, the failure to disinfect rooms is a major misstep, according to infection-control experts. “It’s a very big deal,” says Dolly Greene, chief executive officer of Infection Prevention & Control Resources, which trains nursing home workers. “The environment can be a source of transmission.”

Ten miles away at Bethany Center, a two-story brick building capable of housing 180 people, supplies were stretched so thin that nurse’s aides would scramble at the beginning of each shift to gather up the few clean towels they could find. Workers, such as Woldemariam Fersha, a nurse’s aide who started there in 2005, would come home and complain about it. “He was frustrated,” says Yerom Eshete, his wife. “They don’t provide workers everything they need to take care of patients.”

Another Bethany Center aide, April Avery, was assigned to work the home’s isolation unit. But the bins that were supposed to contain gowns, gloves, and other protective equipment were frequently empty, she says. Patients in the rooms still needed help, so aides would simply go in and out without the proper equipment. Then they’d go work in other parts of the building. “I felt like they were putting me in danger, and I was putting the residents in danger,” Avery says. She quit her job in mid-April.

Later that month, after the first cases were detected at Bethany, Fersha was given only two disposable surgical masks to reuse. Eventually some employees received higher-end N95 masks, which can filter out virus particles. But, according to four staff members, the masks were never fit-tested, a critical step to make sure a proper seal has been established. Two of the workers say they were asked to sign documents that falsely claimed they’d received a fit test. “N95s don’t do what they’re meant to do unless you get fit-tested,” says Greene, the infection-control expert. Bethany Center would eventually record 133 infections and 18 deaths.

More than 300 CareRite workers in Tennessee have contracted the virus so far. Some who reported feeling ill say they came into work at their managers’ request anyway. Two such employees say they had little choice: CareRite offered no Covid-specific sick leave. If an infected worker wanted to be paid while recuperating, they had to dip into their paid time off, or PTO, account. After coming in to save PTO days, one tested negative for the virus. The other was positive, potentially spreading it to residents and colleagues.

As states have attempted to restart their economies, and schools reopen to students for in-person classes, the outlook for nursing homes is as challenging as ever. Infections are soaring among children and younger adults, with the median age falling from 46 in May to 38 in August, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. But a spike among young adults typically leads to an increase among their elders, according to the CDC. Sick kids inevitably infect their parents and grandparents.

The spread of the virus is especially troubling for CareRite given its recent track record. In New York, for instance, where it operates more than 3,000 beds at 15 homes, the company’s 336 Covid-related deaths represent a fatality rate that’s 75% higher than the average for nursing homes in the state. In Florida its 73 fatalities at four homes is also above the average. Across all of its facilities, at least 499 people living or working at CareRite have died from the virus.

Even so, CareRite’s Tennessee facilities are now pitching themselves as virus experts. On July 17, Trevecca Center announced it would begin taking in Covid-positive patients from a nearby assisted living facility. “As a trusted partner of the Tennessee Department of Health, we have had the opportunity to showcase our outstanding clinical capabilities throughout the Covid-19 pandemic,” declared Trevecca’s Young in a press release. A health department spokesman says the department isn’t aware of any partnership.

The decision to take in Covid patients perplexes Cliff McGill, whose 93-year-old mother, Anna Ruth, has been at Trevecca for the past three years and has tested negative for the virus so far. Even before the virus hit, McGill worried about his mom. The facility had seemed short-staffed. Sometimes her fingernails would be filthy or they’d forget her milk at lunch. When the virus struck, communication was lacking. “We learned about the infections on the news,” he says. Later the home moved Anna Ruth to another room without telling him, leaving him unable to reach her for a while. The prospect of Trevecca seeking out more Covid patients worries him. Says McGill: “I want to know they can take care of the people who are already there.”

At CareRite’s Bethany Center, some employees and their families say his concern is well-founded—and not just for residents. After Fersha, the nurse’s aide, was assigned to work with Covid patients, he felt fine at first. He even got a thank-you card from his superiors praising his teamwork and calling him a “superhero.” But at the end of May, he had aches and a bad cough. He stopped going to work and began dipping into the PTO he’d accrued over the years.

Eventually, his wife, Eshete, took him to a drive-thru testing center. Fersha was positive. Over the next few days his condition worsened, and on June 10 he and Eshete called CareRite to let the company know. Eshete says her normally soft-spoken husband, a devout Christian who spent much of his free time reading the Bible, lost his composure. “You did me like this,” he told his supervisor. “Every time, you sent me to work with the Covid patients. You didn’t rotate me.”

“I’m so sorry, I’m so sorry,” the supervisor answered, according to Eshete. By the following day, Fersha was struggling to breathe and was admitted to a hospital. He remained there, running through most of what was left of his PTO. On July 7, he died.

After Fersha’s death, Bethany Center gave Eshete $1,500, and a manager urged her to call if she needed anything. Eshete called a couple of weeks later to say she was struggling to pay her bills on the $16.58 per hour she made as a machine operator. The manager apologized and said CareRite wouldn’t be able to help with that.

Read next: Private Equity Is Ruining Health Care, Covid Is Making It Worse

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.