For Teachers Unions, Classroom Reopenings Are the Biggest Test Yet

For Teachers Unions, Classroom Reopenings Are the Biggest Test Yet

(Bloomberg Businessweek) -- By early August, the Chicago Teachers Union had its fill of magical thinking. After a spring of virtual learning, Chicago, like many cities around the U.S., was pushing toward reopening classrooms in the fall. The revival of the local economy seemed to hinge on parents’ ability to get back to work, and plenty were desperate to get their kids somewhere, anywhere, just out of the house.

Teachers around the country had spent weeks campaigning against reopenings. They’d flooded school board meetings, governors’ mailboxes, and Facebook news feeds, posting versions of their own obituaries. Even U.S. infectious disease chief Anthony Fauci, the face of America’s Covid response, left some teachers feeling they’d been judged acceptable losses. “Though this may sound a little scary and harsh—I don’t mean it to be that way—you’re going to actually be part of the experiment,” Fauci said on July 28, during an online Q&A session organized by the American Federation of Teachers.

“I do not want to be an experiment,” Andrea Parker, an elementary school language arts teacher, told the crowd at a Chicago protest on Aug. 3. “I do not want to be the sacrificial lamb.”

Chicago Teachers Union Vice President Stacy Davis Gates says CTU was fielding calls even from local principals saying, “You guys got this, don’t you?” They did. On Aug. 5, the morning after news broke that the union would hold an emergency delegates meeting to discuss striking, America’s third-largest public school system said it would continue remote-teaching its 350,000 students until at least November.

With the pandemic raging, America’s failure to prepare its public schools for a new year has left teachers, students, and parents facing impossible choices. Remote teaching is its own kind of experiment and carries its own costs. After doing their best to muddle through the summer, some parents are leaving the workforce to watch their young kids. Others who live paycheck to paycheck are wrestling with the risk of their unsupervised children falling behind, as well as missing out on school meals.

And yet Covid has killed more than 200,000 Americans; pushing millions back into classrooms could kill a lot more. Even if most kids won’t die or get badly sick from the virus, they can still get it and spread it. Underfunded schools, where teachers already have to buy their own markers and masking tape, often also lack ready supplies of masks, or the ventilation that would help keep kids and adults safer.

To help cut the risks of classrooms enough to justify the rewards, many American communities will have to spend a lot more money to make their schools safer, and that still won’t be enough by itself. It’s also essential to curb the kinds of community spread that have spiked as businesses have reopened in much of the country, says David Michaels, a public-health professor at George Washington University who ran the Occupational Safety and Health Administration under President Obama. “Governors have made the choice that opening bars is more important than opening schools,” Michaels says. “We’re paying the price for that now.”

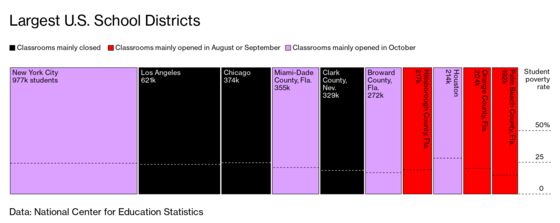

In August, within days of reopening, schools in Indiana, Louisiana, Tennessee, and other states closed because of outbreaks. One Georgia district had to quarantine almost 1,200 students and staff; in Arkansas, the teachers union in Little Rock called a halt to in-person instruction. The country’s largest school district, New York City, started reopening its 1,800 public schools at the end of September and closed 124 right back up the next week. New York’s per capita Covid numbers are much better than those in the Deep South, but hot spots in parts of Brooklyn and Queens have seen a major resurgence over the past several weeks, and the local union and Mayor Bill de Blasio pushed Governor Andrew Cuomo to shut down schools there.

Under pressure from teachers, many of the biggest U.S. school districts have held off longer, including Chicago, Houston (virtual classrooms until Oct. 19), Las Vegas (virtual until at least late October), and Los Angeles (at least November). The nasty outbreaks in other districts and on college campuses suggest these moves have saved lives. They’ve also shown that after a decade of battles about whether teachers are the U.S. school system’s victims, villains, or heroes, teachers have built up enough clout to force cities to listen. Using a playbook that was pioneered in Chicago and has evolved elsewhere, teachers have fought—both within their unions and without—to make sure their communities can’t ignore the risks they’re being asked to take.

Of course, teachers aren’t a monolith, parents’ safety concerns have also proven pivotal, Covid isn’t disappearing by November, and no district has firmly settled the question of what comes next. Some teachers say they’re eager to return to class and they can handle the relevant safety procedures, but many have made clear they don’t feel equipped to police students who ditch their masks or lurch within 6 feet of classmates. Given the demographics of American teaching, it’s tough not to notice who’s being asked to manage these threats: mostly women, some of whose age or health conditions exacerbate the danger from the coronavirus.

When it comes to avoiding that danger, some teachers’ options are severely limited. In Florida, a state where striking could cost educators their jobs and their pensions, high school English teacher Jessica Torrence says coming to class in Kissimmee since Aug. 24 has driven her through cycles of depression, denial, anger, activism, and anxiety. Overwhelmed one day, she vomited into a plastic bag in a classroom closet. “It’s a big game of chicken,” she says, and the fear of retribution has kept Florida’s teachers from gambling on a strike. Just mention the word, she says, and “people scatter.” Before returning to work, Torrence wrote a will for the first time. She had it witnessed during her son’s socially distanced fifth birthday party.

The new era of U.S. teacher power began taking shape in 2010, when a group of activist teachers took control of the Chicago Teachers Union. They called for a more confrontational campaign against then-fashionable education reforms such as the “turnarounds” that disproportionately shut down Black schools there. The tactics they modeled have since been adopted around the country. They revolved around the most basic union principle of all: strength in numbers. CTU got serious about organizing inside and outside of school, pushing colleagues to participate more actively in the union’s work. They won support from parents by identifying shared priorities, such as smaller class sizes, under the banner “the schools Chicago’s students deserve.” And then they struck.

During contract negotiations in September 2012, Chicago’s teachers took to the streets for a week—the union’s first strike in a quarter-century—demanding smaller classes, more teachers, and less emphasis on standardized testing. The city argued in court that the “noneconomic” grievances made the strike illegal, but the teachers won 15-student caps on special education classes, commitments to hire more art and gym teachers, and restrictions on the importance of test scores in teacher evaluations. “Having the authorities understand that we will shut down your city” was pivotal to the union’s success, according to its then-president, Karen Lewis. “You will not be able to function without dealing with us fairly.”

At the time, teachers seemed to have few friends in either party. Chicago’s then-Mayor Rahm Emanuel, a Democrat, was previously President Obama’s chief of staff, and the schools chief who’d rankled the city’s activist teachers had become Obama’s secretary of education. That summer’s Democratic National Convention included a speech from Deval Patrick, then the governor of Massachusetts, celebrating a school that replaced most of its teachers following Obama’s education reforms. The next year, voters in deep-blue New Jersey handed a landslide reelection victory to Republican Governor Chris Christie three days after a crowd cheered him for angrily berating a special education teacher who asked why he kept casting schools as “failure factories.” The crowd around them ate it up when Christie replied, “They fail because you guys are failing.”

That teacher, Melissa Tomlinson, says the crowd’s cheers for Christie made her realize just how much blame her profession was shouldering for America’s underfunded education system. While continuing to teach, she now also heads an activist group called the Badass Teachers Association, one of several pushing union leaders around the country to follow Chicago’s lead. Those efforts have advanced in part through activist takeovers of union affiliates in places such as Baltimore, Los Angeles, and Oakland, Calif., and in part through teacher protests that have defied local union leaders’ plans.

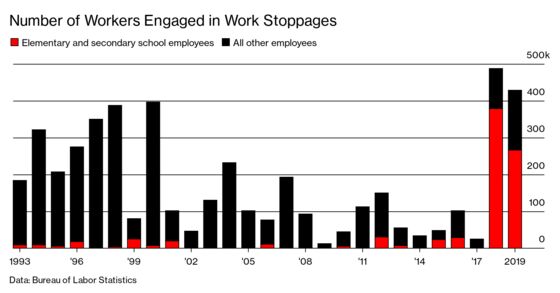

By 2018, teachers were on the offense. Large numbers of parents sympathized, fed up with policies that fixated schools on high-stakes tests. And for many, the push toward charter schools had sounded a lot better coming from Obama than it did from Betsy DeVos, President Trump’s billionaire secretary of education. A new wave of strikes began with about 20,000 school employees in West Virginia, spurring similar actions in red states including Kentucky and Oklahoma. Despite lacking legal protection for their work stoppage, the West Virginians refused to end their strike even after union leaders said they would. They waited another full week, until the governor signed a 5% raise for teachers, whose pay had averaged roughly $46,000, as well as for other state workers.

In Arizona that year, Phoenix math and science teacher Rebecca Garelli, who’d recently moved there from Chicago, posted on the Badass Teachers Facebook page that she wished her new home state would follow West Virginia’s lead, too. Activists in other states replied that she should make it happen. Soon, Garelli and a handful of other teachers were training colleagues in about 1,200 Arizona schools to organize protests. West Virginia helped make clear that teachers could fight for better treatment without waiting for union leaders’ permission, says another organizer, Noah Karvelis. “It was like, anybody can do this, this is a thing, the strike is still alive,” he says.

Arizona teachers’ statements of solidarity, such as showing up to work in red T-shirts, escalated into a weeklong strike. Joe Thomas, the head of the state’s union, says he provided advice and resources but the activists took the lead. Thomas says his attitude was: “If these people I’ve never seen before are the answer, hallelujah, I’m with them.” The teachers won a promise to hike their pay 20% over three years.

By the time Covid arrived in the U.S., years of reinvigorated unionism gave teachers a voice and power they otherwise might not have had. In March, Chicago’s teachers joined with labor and community groups to demand that the city halt evictions, expand paid time off, and deliver school lunches to children in need. There and in other cities that had followed the same model, teachers helped drive school districts to shift quickly to remote learning. By the end of March, union leaders and activists such as Garelli were already holding Zoom calls to figure out how to approach the fall.

“You have everybody from the Trumpers on down saying, pretty much, get your asses back into the building,” says Cecily Myart-Cruz, president of United Teachers Los Angeles, which represents educators in the country’s second-biggest school district. “When you see the infection rates going up, there’s just no way in good conscience you could actually have students coming in.”

Over the past six months, America’s teachers have protested classroom reopenings on Facebook, through the mail, and in person at school board meetings. They’ve hoisted mock coffins in protest processions and adorned their cars with poster slogans such as “Go virtual, not viral.” A school district east of Phoenix had to cancel the first days of class after teachers staged a sickout. Activist union locals teamed up with groups such as the climate-focused Sunrise Movement to hold coordinated protests in dozens of cities on Aug. 3 and again on Sept. 30, demanding that schools be kept closed until science shows they’re safe. Their other demands, some more aspirational than others, included that schools reopen free of cops as well as Covid and urged the hiring of more school nurses, cancellation of rent, and moratoriums on charter programs and standardized tests.

In keeping with the Chicago playbook, teachers around the country have been working to deepen ties with parents. In West Virginia they’ve consulted with parents and legislators on ways to adapt special education instruction for remote learning. In Arizona, parents and teachers have conducted joint “motor marches” in their cars. (Sample sign: “Remote learning won’t kill us, but Covid can.”) In Chicago they’ve hosted a daily educational television show on the local Fox station, dropped off diapers at parents’ homes, and checked in regularly by phone. “You can’t just be calling parents saying, ‘Hey, your kid is f---ing up,’ ” says 11th grade social studies teacher Jackson Potter, one of the activists who helped reinvent Chicago’s union a decade ago. “We’re in it with our parents.” Polls suggest that most parents, like most teachers, think schooling should be mainly remote for now, with some openness to hybrid models that put smaller numbers of kids in classrooms with appropriate safety measures.

The two big national unions, the National Education Association and the American Federation of Teachers, have emphasized their eagerness to get kids back into classrooms as soon as it seems safe while insisting that districts avoid reckless reopenings. NEA President Becky Pringle says her union supports and reinforces the tactics of its members and affiliates. “We are not managing them,” Pringle says. “We are listening to them.” In July, the AFT’s executive council passed a resolution backing safety strikes “as a last resort.” Randi Weingarten, the AFT president, says, “I love the advocacy. I may disagree with it sometimes, but I love it.” Still, she says, she worries about some left-wing activism being “misrepresented” to paint the union as an undue obstacle to classroom reopenings.

All of this gets extra complicated in places such as Florida, where teachers who participate in strikes, under state law, can be fired and stripped of their teaching credentials and all the money accumulated in their pensions. Even basic wins are tough to come by. Eric Rodriguez, a teacher and local union president in Florida’s Suwannee County, has been pushing for a simple in-school mask mandate. No, the state still doesn’t have one.

Parts of Florida have been sending teachers in since mid-August, even as the state reported roughly 5,000 new Covid cases a day. “Just as the SEALs surmounted obstacles to bring Osama bin Laden to justice, so, too, will the Martin County school system find a way,” Governor Ron DeSantis said during a speech in August. “All in, all the time.” To compel some reluctant districts to reopen classrooms earlier than they wanted, the state threatened to claw back tens of millions of dollars in funding. Under orders from DeSantis’s education commissioner, the state’s largest counties, Miami-Dade and Broward, resumed in-person schooling earlier in October than planned.

Rather than choose between bars and schools, DeSantis reopened both at once. Florida, which held off on a statewide stay-at-home order until April, first took its watering holes off the lockdown list in June, then had to shut them again later that month following a surge in coronavirus diagnoses. On Sept. 25, two weeks before the biggest school districts reopened, DeSantis signed an executive order mandating that local governments let bars and restaurants reopen at 50% capacity or more.

At B.D. Gullett Elementary School in Bradenton, Fla., Principal Todd Richardson says the protests he’s seen on TV don’t represent what he’s heard from his teachers. He reopened classrooms on Aug. 17, with giant balloon characters and a gator-costumed parent on hand to celebrate, and only one student has tested positive, he says. (Some students have had to quarantine after being exposed elsewhere.) Several parents who’d initially opted for remote learning reconsidered within days of trying to keep their children learning from home, Richardson says. “I don’t want to kill my kid” was a common refrain, the principal recalls. “I want him to come back to school.”

Nicholas Leduc, a fourth grade teacher at nearby Barbara A. Harvey Elementary School, says he had zero reservations about in-person learning but plenty about remote. “I worry about the long-term implications of kids having no social interaction,” Leduc says, “to have kids on a therapist’s couch because they didn’t talk to another kid for a year and a half.” Leduc says he’s getting kids “as sanitized as possible” by wiping down tables, desks, and dividers, and being stringent about masks, face shields, and regular handwashing.

Even in Florida, though, zero reservations is the minority position. The Florida Education Association, a union representing about 300,000 school employees, sued the governor and education commissioner in state court, arguing that their mandate for in-person schooling was an unconstitutional overreach into local affairs and should be struck down. In August a judge ruled in the union’s favor, but the appeals court overturned the ruling, saying it was the lower court that had exceeded its constitutional authority.

Given the tools at their disposal, Florida teachers can’t exactly follow the Chicago playbook. In July, after teachers in Florida’s Duval County started talking about the possibility of a strike, the local union sent out an email telling them to “be smart” and warning that “striking is against the law and will have life-altering consequences.” Then again, West Virginia’s teachers had no legal right to strike in 2018, either, but enough did that the state caved and raised their pay. “I’m of the mindset that there’s no such thing as an illegal strike, just an unsuccessful one,” says Alex Ingram, a seventh grade civics teacher in Duval County. He and dozens of colleagues staged a sickout on their first day of classes in August but haven’t been able to escalate their resistance beyond that. After one week back, Ingram was self-quarantined because of Covid-19 symptoms and a student’s positive test result.

Ingram says classroom reopening has been as bad as many feared. Cardboard dividers between desks have forced kids to crane their necks toward one another to see the board. There’s inadequate sanitation and ventilation, he says, and mask use is inconsistent among his students and even worse among their elementary school counterparts. “They’re kids,” he says. “They don’t wear their shoes, either.”

The AFT released polling in September showing that, though most teachers oppose reopening now, 79% would be up for it if local infection rates were low, testing were readily available, and there were safety measures including masks, daily deep cleaning, open windows, and virtual alternatives for at-risk kids and adults. Instead, the Miami teachers union has been pleading for locals to donate hand sanitizer, saying the state has left cash-strapped schools without it.

It bears repeating that America’s leaders have offered no coherent, cohesive, or adequately funded plan to reopen classrooms. They’ve simply run out the clock on the country’s children, parents, and teachers. This response has forced many teachers—like fast-food cashiers, meatpackers, warehouse haulers, and all sorts of people deemed essential workers—to weigh their fear of retaliation for staying home against their fear of Covid. Many are casting around for least-bad alternatives.

Some have nabbed remote-only teaching assignments. Many others have taken leaves of absence or early retirement. If enough teachers organized resistance, they could stop premature reopenings and save more lives, says Damaris Allen, a parent activist in Florida whose teens are learning from home this fall. “I don’t want to put that responsibility in their laps, because they’ve had so much responsibility already put on them,” says Allen, a former Hillsborough County Council PTA president. “I also know that they have all the power right now. But they’re really scared.”

Read next: Economist Emily Oster Is Helping Parents Stay Sane in the Coronavirus Pandemic

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.