Heated Montana Race Could Flip the Senate to Democrats

Heated Montana Race Could Flip the Senate to Democrats

(Bloomberg Businessweek) -- Montana’s Battle of the Steves started at the buzzer. On the morning of March 9, the last day to file as a challenger to U.S. Senator Steve Daines, the first-term incumbent held a commanding lead in his bid for reelection. Daines, a former software executive and reliable Republican ally of President Trump, was considered a lock over the scattered field of little-known Democrats who’d declared their candidacies. But that was before the secretary of state’s office at the Capitol in Helena received a last-minute visitor: Governor Steve Bullock, a two-term Democrat and the state’s most popular politician, who arrived to submit his filing papers from his office across the hall. “We decided that this wasn’t a time to be on the sidelines,” Bullock said after filing.

Bullock’s entry upended the Senate race. Most of the half-dozen other Democratic contenders quickly withdrew, and suddenly the party seemed to have a chance. Daines has swayed undecided voters since July and narrowly retaken the slim advantage the governor held in early polls, but most survey results so far have remained firmly within the margin of error. The Bullock-Daines election seems likely to be among America’s most competitive on Nov. 3, and with Republicans nursing a fragile 53-47 majority in the Senate, Montana’s might just be the unlikely seat that flips the upper chamber into Democratic hands.

The campaigns declined to make the candidates available for interviews for this story. In an email, the Bullock campaign said the governor will put Montana’s needs ahead of party leaders and individual interest groups. The Daines campaign said Bullock is too focused on defeating the president. As the Republican National Convention began in late August, Daines told the Billings CBS affiliate that “Montanans want to elect a senator who’s going to stand with President Trump.”

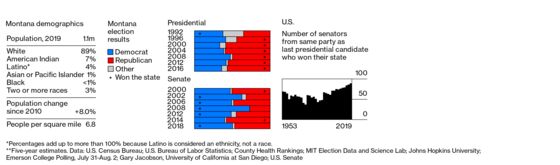

Four years ago, Trump won Montana by 20 points. Today, with more than 180,000 Americans dead from Covid-19, including about 90 Montanans, he’s still comfortably leading former Vice President Joe Biden by about half that margin. Montana has voted Republican in every presidential election since the 1960s with the exception of Bill Clinton, who benefited from third-party candidate Ross Perot’s strong showing there in 1992. And since then, the Senate map has come to much more sharply resemble the Electoral College, because most Americans now cast their ballots for the same party all the way down the ticket. A generation ago fewer than half the country’s 100 senators came from the same parties that won their states’ presidential votes; now the number stands at 89. (Among the Senate seats in contention in 2016, that Venn diagram was a circle.) For the most part, the cliché that all politics is local seems out of date in the U.S.

Montana is an outlier. Although Republicans rule the statehouse and these days tend to win the state’s only seat in the U.S. House of Representatives, voters have elected Democrats in the past four gubernatorial campaigns and five of the past six U.S. Senate races. “It’s a populist purple state,” says David Parker, a political scientist at Montana State University who’s focused on recent Senate campaigns.

As governor, Bullock has embodied some of the contradictions and nuances of a massive state with 1 million people and an outdoors-centric economy. He supports a public option, a government health insurance program to compete with private plans, but not the single-payer health insurance system often called Medicare for All. He supports freezes to college tuition and greater state spending on education but not the cancellation of student debt or free tuition for public colleges. And he supports running the long-delayed Keystone XL oil pipeline through Montana, as long as it’s in consultation with American Indian tribal leaders and nearby landowners.

There are three perennial targets in Montana elections: Big Government, big corporations (notably Big Pharma), and outsiders, loosely defined as anyone who didn’t grow up there. Bullock’s last gubernatorial campaign stressed the New Jersey origins of a rival who’s lived in Montana since the 1990s. Two years ago, Montana’s senior senator, Democrat Jon Tester, narrowly won a third term after branding his opponent, who moved to the state in 2002, as “Maryland Matt.”

That’s not really an option against Daines, a fifth-generation Montanan who’s lived there with few exceptions since 1964. Instead, the Senate campaign so far has revolved around the questions of who truly has local interests at heart, who’s delivered better results for Montana during the coronavirus pandemic, and, yes, Trump. Two years ago, Tester ran hard on his record of working with the president to help Montana’s many veterans and first responders—while fighting the White House at times when he thought those interests were at risk. With outside money flowing into the Senate campaign at a record pace, Bullock, who supported Trump’s impeachment last year, will test just how local his state’s politics still are.

Born in Missoula in 1966, Bullock grew up in Helena, delivering newspapers to the governor’s residence starting in elementary school. (One of his stock jokes: “I’ve made it four blocks in life.”) His school board mother mostly raised him and his brother after divorcing his teacher father. A couple of years after Bullock graduated from Columbia Law School with six figures of student debt, though, it was his dad, dying of lung cancer, who helped lead him back to Montana. While caring for his father, Bullock got a job as a staff lawyer at the Montana secretary of state’s office. A few years later he’d become the chief deputy of the state’s attorney general, and then, after a stint in private practice, the AG himself. In that post he defended Montana’s century-old ban on corporate election spending, though he lost in the U.S. Supreme Court after it significantly deregulated campaign finance with its Citizens United ruling.

Bullock narrowly won the governorship in 2012 on the promise to safeguard unions by vetoing right-to-work bills, give every homeowner a $400 property tax rebate, and protect hunting and fishing. During his two terms he’s worked with Republican legislators to expand Medicaid to cover more than 90,000 Montanans and keep rural hospitals open and to force all groups engaged in late-game political spending to disclose their donors. (Another Bullock favorite: “Make Washington work more like Montana.”) He’s failed to push public funding for preschool through the legislature but has managed to block tax cuts favoring higher-income residents and regularly used his veto power to protect abortion rights.

Under Montana’s term-limit law, Bullock has to leave the governor’s residence next year. Non-Montanans can be forgiven for missing his campaign for president, which lasted more than six months; he ran mostly on campaign finance reform and his record of attracting Trump voters, and he qualified for only one Democratic debate. Before and after, he strenuously denied any interest in challenging Daines. But national Democratic Party leaders saw Bullock’s popularity as an opportunity. Former President Obama met with the governor in February to ask him to run against Daines, as did New York’s Chuck Schumer, the Senate minority leader. On March 9, Bullock became the only sitting U.S. governor running for the Senate.

And that was before Montana knew just how bad Covid-19 was going to get. Bullock declared a state of emergency on March 12, closed public schools on March 15, and ordered Montanans to stay at home on March 26. He issued a mask order in July, after cases started to rise. “Montana was doing very well and had some of the lowest cases,” says Jeremy Johnson, a political scientist at Carroll College in Helena. “Now it’s crept up somewhat, but he’s maintained a high approval for his handling of the Covid crisis.”

Daines says Bullock has been slow to distribute the more than $1.2 billion in federal pandemic relief that Montana received in March. Daines, 58, has defined himself as a staunchly conservative Republican, deep red where Bullock is purple. He opposes abortion rights and gun restrictions, and voted for the 2017 tax cut law that concentrated its relief on corporations and the wealthiest taxpayers (only, however, after his colleagues amended it to increase cuts for small businesses). Daines is the kind of politician Montanans tend to elect to their lone U.S. House seat, a position he held for two years before his current post. The House seat was his first political office, but he’d been rising in state Republican circles for some years before that, most notably as the candidate for lieutenant governor on a ticket that failed to unseat Bullock’s predecessor, Democratic Governor Brian Schweitzer, in 2008.

Daines grew up in Bozeman, the son of a local construction company owner and a homemaker, and got his chemical engineering degree from Montana State University. He spent much of his time out of state shortly thereafter, managing operations for Procter & Gamble Co., including by opening factories in Asia for a handful of years. (Daines lived in China, now a focus of campaign attacks.) After he returned to Bozeman in 1997 to work for his family’s business, he made a well-timed investment in RightNow Technologies Inc., a software company that became a pillar of the local economy, then went to work there.

At RightNow, Daines managed customer service, sales, and the company’s Asia-Pacific operations, and he made a small fortune when Oracle Corp. bought the company in 2012. (His financial disclosures from that year indicate income of $1 million to $5 million from Oracle stock options.) He left shortly thereafter and won his congressional race that fall.

After one term in the House, Daines in the Senate has helped win a partial lifting of China’s 14-year ban on U.S. beef imports, aid for Vietnam veterans with health conditions linked to the chemical weapons U.S. forces used in that war, and federal recognition of Montana’s Little Shell Tribe of Chippewa Indians. (About 7% of Montanans identify as American Indian, more than the state’s Black and Latino populations combined.) The accomplishment Daines’s reelection campaign most frequently cites is a recent one: He co-sponsored the Great American Outdoors Act, which helped more permanently funnel federal royalties from oil and gas drilling to conservation. Environmental groups, including those that have endorsed Bullock, cheered the bill’s passage.

Trump signed the conservation bill into law on Aug. 4, during a photo op in the White House’s jumbo East Room. The president took the opportunity to praise Daines, a co-author of the Senate bill who chairs the chamber’s national parks subcommittee and was there for the occasion, looking over his left shoulder. (Daines wore a mask; Trump didn’t.) “He’s a fantastic man, a fantastic senator,” Trump said of Daines just before signing the bill. “He’s done a wonderful job. He loves his state, and he loves our country.”

The bill signing was something of an exclamation point on Daines’s relationship with the president. As with most Republican senators who aren’t Mitt Romney, it’s difficult to overstate the extent to which Daines has tethered his career to Trump. The lead image on Daines’s campaign website is a massive photo of Trump speaking in front of a crowd of fans wearing MAGA hats while Daines looks on from the side, smiling.

Daines’s stalwart Trump loyalty has put him in the awkward position of championing the president’s catastrophic response to Covid-19, which has left the U.S. among the nations worst hit by the pandemic and one of the few that seem unable to contain it. “President Trump has led boldly,” Daines said a few days after the bill signing in his first debate with Bullock, conducted via Zoom connections from their homes because, you know, Covid. “I’m grateful for his leadership in this very, very difficult time.” Daines predicted that a coronavirus therapy or vaccine was only six months away—a testament, he said, to Trump’s ability to unite government scientists with the private sector.

In the debate, Daines also sought to cast Bullock as the real Washington insider, a stalking horse for national Democrats. “We don’t need another person back in Washington, D.C., that gives Chuck Schumer the majority control of the United States Senate,” Daines said. “That gives Nancy Pelosi truly unchecked power.” In less than an hour he mentioned Schumer 10 times, House Speaker Pelosi 5 times, and Obama 3 times. In response, Bullock noted that those names won’t be on Montana ballots in November. “Unfortunately,” he said, “Senator Daines has to run against me.”

The debate eventually turned to public lands. Daines called the Great American Outdoors Act “a great accomplishment, years in the making.” Bullock said his opponent didn’t show the same commitment to conservation before it started to look like he needed help conserving his own job. Daines parried by citing Bullock’s slight moves to the left on gun rights during his presidential campaign. Last year the governor voiced support for universal background checks and a ban on certain high-powered weapons—centrist proposals that are broadly popular on a national level but a much tougher sell in Montana. Bullock said that those positions don’t make him any less of a Second Amendment supporter and that while he sees gun violence as a public-health issue, he has stood up to “Washington Democrats” to defend gun rights.

The other big issue was health care. Besides the public option, Bullock supports using the federal government’s purchasing power to negotiate cheaper prescription drug prices. The Democratic-led House passed a bill to allow just that in December, but the Senate hasn’t taken it up. Daines, who has a vote on the U.S. Senate Committee on Finance, voted last year to cap Medicare’s price increases at the rate of inflation and limit seniors’ out-of-pocket prescription drug costs to $3,100 a year. Even though he voted with his Republican colleagues to repeal Obamacare, Daines has also said he wants a new law to restore protections for preexisting conditions.

The candidates have two more debates before Election Day. In the meantime they’ll be holding virtual campaign events with supporters while ads blitz local TV stations. (Montana networks ran more than 41,000 Senate campaign ads from July 15 to Aug. 9, more than in any other state, say researchers at Wesleyan University.) The race remains a toss-up, but Trump appears almost certain to win Montana by a much smaller margin than he did in 2016, which likely means Bullock will have to siphon fewer Republican voters than he did in his last gubernatorial bid, says Jessica Taylor, the Senate and governors editor for the Cook Political Report, a nonpartisan newsletter that analyzes elections. In Taylor’s view, Bullock has the advantage when it comes to current events. “We’ve seen governors get much higher marks for their handling of coronavirus than Washington has,” she says.

This is Bullock’s first time challenging a Republican incumbent, and Republican politics has become much more tribal in a short period of time, in ways that could well validate Daines’s years as a loyal Trump foot soldier. If Bullock squeaks out a win a couple of months from now, it’s likely that national Democrats will be having a good night in bellwethers such as Arizona and North Carolina. Yet to win control of the Senate in 2021—and with it the goal posts for the White House’s agenda, personnel, and judicial nominees—it might not be enough for Democrats to win bellwethers. They might need outliers, too. —Greg Giroux is a reporter for Bloomberg Government

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.