‘Crazy Fast’ Vaccine Race Has Drug Companies Pushing Their Limits

‘Crazy Fast’ Vaccine Race Has Drug Companies Pushing Their Limits

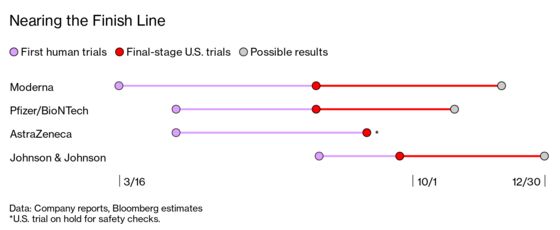

(Bloomberg Businessweek) -- On March 16, just two months after researchers deciphered the genetic code of the coronavirus that causes Covid-19, Moderna Inc.’s vaccine began human trials. Now, no less than four Covid vaccines are hurtling toward the finish line in the U.S. Moderna and Pfizer Inc., along with its German partner BioNTech SE, are leading the pack with vaccines that require two doses, while a single-shot vaccine from Johnson & Johnson began a late-phase trial last week. “This is beyond unprecedented,” says Otto Yang, a viral immunologist at UCLA. “It is crazy fast.”

There may never have been anything like this pedal-to-the-metal race in the history of vaccines. But will they work? And will enough people take them, especially amid the political turmoil surrounding their development?

Safety problems are unlikely, but not unheard of. In 1999 a new vaccine for rotavirus in infants was recalled after it caused cases of bowel obstruction that were missed in trials. And in 1976, after federal officials rushed out a mass vaccination campaign for swine flu, the program was shelved after about 1 in 100,000 people who got the shot developed Guillain-Barré syndrome, a rare neurological disorder.

Treatments that show promise could be brought to market quickly under so-called emergency use authorization, a lesser standard than full approval and one that’s rarely used for vaccines. But that standard “is very loose,” says Peter Doshi, a professor at the University of Maryland School of Pharmacy. “We could easily have very little data.” Under an emergency authorization, vaccines would probably go first to health-care workers, first responders, or the elderly.

Not helping matters is President Donald Trump’s threat to override minimum requirements in order to get a vaccine to market even faster. Trust in the process is plummeting: Only 51% of American adults say they would likely get a Covid-19 vaccine, down from 72% in May, according to a Pew Research Center poll. “You can have the best vaccine in the world,” says Leana Wen, an emergency physician and public-health professor at George Washington University, “but if people aren’t taking it, it’s a failure.”

The big trials are aimed at preventing symptomatic cases of Covid. If they work, they should provide solid evidence that the shots are at least partially effective at preventing Covid-19 symptoms—at least in the short term.

Each trial relies on about 30,000 healthy volunteers or more. Half get placebos, while the other half get the vaccine. Tests continue until enough cases can be tallied to show the illness rate is reduced by at least half, the minimum Food and Drug Administration requirement.

But big drug and vaccine studies usually allow monitors to get an early peek at the data once or twice before the planned end. The panel can recommend stopping the trial early if a treatment is judged overwhelmingly effective—or, alternatively, a total dud.

Pfizer, which has the most aggressive plan, has given itself four preliminary looks at the data in a bid to quickly reach a conclusion in its 44,000-person trial. The first look could occur any day now, according to Airfinity Ltd., a London-based analytics firm tracking vaccine trials. Pfizer has said it expects conclusive results by the end of October; but it plans to continue the trial to obtain complete safety data. Outside experts say the approach is unusually bold.

Many public-health officials say the most important goal of a coronavirus vaccine is to prevent deaths, hospitalizations, and serious complications. But that isn’t the primary goal of most of these trials, which are focused first on reducing symptomatic cases. Pfizer’s trial, for instance, counts milder cases. According to Airfinity, both Pfizer and Moderna won’t be in a position to determine whether their vaccines prevent hospitalizations until February.

That means doctors initially may have little information about how well the vaccines work at preventing serious illness, says Eric Topol, director of the Scripps Research Translational Institute, who has been critical of the way the trials were designed. “We want to know this vaccine has strong efficacy,” he says. “And that means two things: that it works in the majority of people and that it works to prevent serious infections, not sore throats or muscle aches.”

Pfizer’s trial was designed to evaluate its vaccine candidate “as fast as possible,” said Amy Rose, a spokeswoman, in an email. The company has worked with government scientists to develop best practices for testing and based its schedule for interim analyses on the vaccine’s “strong profile” in early human trials and animal tests, she said. Moderna’s trial was agreed upon with U.S. regulators, spokesman Ray Jordan said in an email. Johnson & Johnson’s trial, meanwhile, has stricter criteria for declaring early success, according to Airfinity. The company says it won’t seek approval before it has sufficient safety and efficacy data.

The Covid-19 vaccine trials are large enough to rule out relatively uncommon side effects, ones that may occur in 1 in 1,000 or 2,000 people. But they can’t rule out rare side effects that occur in, say, 1 in 20,000 people. Only long-term follow-ups once the vaccine is on the market can do that. Says University of Florida biostatistician Natalie Dean: “You really need impeccable safety.”

Some scientists are also worried a vaccine will be authorized before there’s time for adequate follow-up during the trial itself. The FDA would like drugmakers to provide at least two months of safety data, because that’s the time period after vaccination in which most serious complications occur. It’s this two-month proposal that Trump may be pushing back against in a bid to get authorization before the November election.

Durability of the vaccine is another critical unknown. And the quicker a vaccine is rushed out, the less researchers will understand its ability to provide lasting protection. “Durability by definition has to be studied over time, and there is not going to be enough time between now and the end of October to really know anything about durability,” says Tony Moody, an immunologist at the Duke Human Vaccine Institute. For other coronaviruses, such as the ones that cause the common cold, immunity tends to fade relatively quickly. For that reason, even if a Covid-19 vaccine works, people may need regular booster shots for years to come.

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.