The World’s Top Pork Processor Is Battling Two Epidemics at Once

The World’s Top Pork Processor Is Battling Two Epidemics at Once

(Bloomberg Businessweek) -- As businesses around the globe buckle under the strain of Covid-19, the world’s biggest pork producer is fighting not just one highly contagious virus, but two. And the outcome could determine whether Americans will have enough hot dogs, bacon, and ham this summer.

Hong Kong-based WH Group Ltd. is struggling to cope with the virus that causes African swine fever (ASF), a deadly malady that’s devastated hog herds and helped more than double pork prices in China, while also spreading to other countries in Asia and Europe. Like Covid-19, ASF is currently incurable and researchers have yet to come up with a vaccine. China’s pork production fell 29% in the first three months of 2020; the swine disease has slashed the size of the country’s hog herd by about half.

Now the coronavirus is piling on. Smithfield Foods, the Virginia-based subsidiary of WH Group, shut three of its U.S. plants this month because of Covid-19. They include a processing facility in Sioux Falls, S.D., that accounts for about a quarter of the company’s U.S. revenue.

When Smithfield announced the indefinite closure, more than 200 workers were sick; that number has risen to more than 700—almost half the state’s total. With the Sioux Falls site alone handling about 5% of all hog processing in the U.S., the maker of Farmland bacon, Farmer John hot dogs, Eckrich sausage, and Armour ham warned of possible supermarket shortages. “The closure of this facility, combined with a growing list of other protein plants that have shuttered across our industry, is pushing our country perilously close to the edge in terms of our meat supply,” Smithfield Chief Executive Officer Ken Sullivan said on April 12. “It is impossible to keep our grocery stores stocked if our plants are not running.”

WH isn’t the only meat company facing virus woes. Tyson Foods Inc. on April 22 said it’s closing its 2,800-worker pork plant in Waterloo, Iowa. Brazilian processor JBS SA had said it would indefinitely close its pork plant in Worthington, Minn., after employees tested positive for Covid-19. And deaths have been reported among workers at Tyson’s pork plant in Iowa and poultry plant in Georgia as well as at Cargill Inc. plants in Colorado and Alberta, Canada. “As we all learn more about coronavirus, it is clear that the disease is far more widespread across the U.S. and in our county than official estimates indicate based on limited testing,” Bob Krebs, president of JBS USA Pork, said in a statement.

Even before the coronavirus disruptions, the world wasn’t producing enough pork. The number of hogs worldwide has declined about 25% because of ASF, according to the U.S. Meat Export Federation. Now the double epidemic raises the specter of shortages that could put WH in the middle of a fight between its two biggest markets, says Brett Stuart, president of Denver-based consulting firm Global AgriTrends. “Smithfield is going to say, ‘I have X amounts of hogs to sell, and the highest bidder gets the pork,’ ” he says. “Could we get to a situation where China is outbidding U.S. consumers for pork? Potentially, yes.” The average wholesale price for pork in China is 45 yuan ($6.36) per kilogram, up from 20.6 yuan a year ago. “If the Chinese buyers call Smithfield and say ‘We need U.S. pork,’ they can potentially bid higher than our consumers or retailers can bid,” Stuart says.

WH also is trying to avoid hits from the U.S.-China trade war. Following President Trump’s first tariffs against its products in 2018, China placed retaliatory tariffs on U.S. pork imports, raising the price of American-made Smithfield meat to Chinese consumers. Still, WH managed to import about 410,000 metric tons of U.S. pork into China last year, vs. about 125,000 metric tons a year earlier.

When Shuanghui International Holdings, the precursor to WH Group, paid about $4.7 billion for Smithfield in 2013, some U.S. lawmakers expressed concern that Chinese ownership would create national security risks, including the possibility of Americans losing access to some pork products. The U.S. allowed the acquisition, and now questions about availability may again arise.

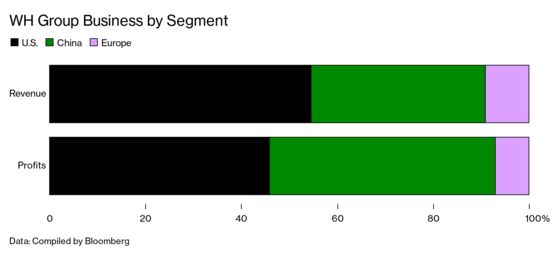

Given the higher prices for pork in China, the U.S. business isn’t as lucrative as WH’s China operations. While China accounted for only about one-third of WH sales in 2019, it generated about 47% of segment profit. WH’s $13.2 billion of U.S. revenue last year was about 55% of its total sales, down from 60% in 2015, but only 46% of segment earnings.

About six weeks before Smithfield closed its South Dakota plant, workers asked the company to implement such safety measures as checking temperatures and staggering lunch schedules for employees, says Kooper Caraway, president of the local arm of the AFL-CIO, which is assisting plant employees. “The management did not take the workers’ demands seriously and did not implement any of the procedures,” he says. “It wasn’t until dozens of workers tested positive that the management decided to implement these things, but by then it was too late.”

A company spokeswoman says that WH Group, through its Smithfield unit, has been adopting what the company calls stringent and detailed safety processes and protocols at its U.S. facilities. Following the Sioux Falls plant’s closure, Smithfield announced $100 million in bonuses for employees, including those who can’t work because of exposure to the coronavirus. That followed an earlier $20 million pledge. —With Shuping Niu and Dorota Bartyzel

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.