Coronavirus Surveillance Helps, But the Programs Are Hard to Stop

Coronavirus Surveillance Helps, But the Programs Are Hard to Stop

(Bloomberg Businessweek) -- An Israeli tech company that specializes in counterterrorism spyware is working with a dozen countries to slow the spread of an invisible enemy known as Covid-19. In China, authorities have deployed facial-recognition software and location tracking in their fight against the coronavirus. And a U.S. big data company with connections to intelligence agencies is talking to governments about how it can help.

It’s not surprising that algorithms and artificial intelligence have been recruited to fight a pandemic threatening millions of lives. Yet around the world, surveillance measures normally used against terrorists and criminals are raising privacy and civil liberties concerns, causing governments from Seoul to Jerusalem to recalibrate their tactics. Some also have had to assure their citizens that the monitoring is only temporary.

The privacy questions are real. What rights can people expect to safeguard? Will measures enacted during a pandemic be dismantled when they’re no longer needed?

“Unfortunately, emergency powers quickly become normal operating procedures,” says Richard Brooks, a computer engineering professor at Clemson University in South Carolina whose research has focused on how human rights activists in authoritarian countries can avoid surveillance. “If the ability to track social contacts exists to stop a contagion, I can guarantee you it will be used to track the spread of dissent.”

Not even ardent privacy advocates dispute the need for rapid responses to an outbreak, including enforcing quarantines and lockdowns as China, Italy, and other countries have done. Typically, health authorities obtain a list of contacts from an infected individual to locate other people, by phone or in person, who may have been exposed. That process, known as contact tracing, is tedious, even more so when there are millions of potential victims. Surveillance technology is now speeding things up. It’s also raising questions about how much governments should know about people’s movements and personal connections.

“Any surveillance measures must have a legal basis, be narrowly tailored to meet a legitimate public health goal, and contain safeguards against abuse,” Deborah Brown, senior digital-rights researcher at Human Rights Watch, said in a joint statement made with Amnesty International, Privacy International, and 104 other organizations. It cited reports that 24 countries are using location tracking, while 14 are using apps for contact tracing or quarantine enforcement.

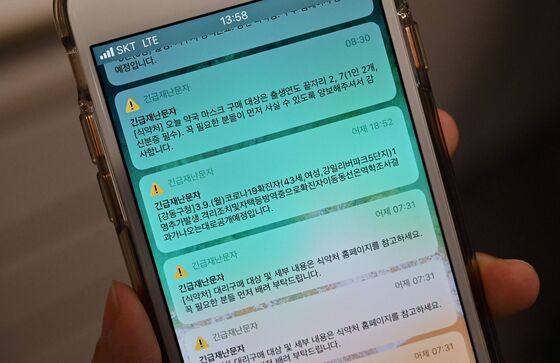

In South Korea, which has been successful in slowing the spread of the virus, authorities are using location data from three mobile carriers and transactions from 22 credit-card issuers to decrease the tracking time of potentially infected individuals to 10 minutes, from one day. They can also request CCTV footage from police.

Initially, the government released so many details about people testing positive for Covid-19 that some were identified, even though their names were withheld, exposing them to public ridicule and harassment. Two people taunted on social media for having an affair because the data showed they were at the same hotel at the same time turned out to have been there for a church gathering.

After a rebuke from South Korea’s human rights commission, the government changed the way it releases information, issued new guidelines to protect privacy rights, and said police would take action against anyone leaking information related to Covid-19. It also pledged to expunge personal data as soon as the pandemic passes.

In China, where surveillance technology has been integrated with tough policing, the government promised to increase privacy measures after criticism about the release of the identities of coronavirus patients. Hu Yong, a new media critic and professor at Peking University with 800,000 followers, said in a blog post that many of the public health surveillance tactics “violated the peoples’ basic human rights and were inherently illegitimate.” The government agreed to allow citizens to give their consent for biometric data collection—but not until later this year.

Chinese authorities have used facial-recognition software and location tracking to identify people with fevers and direct them for testing, as well as to monitor quarantine violators. QR codes on mobile phones are colored, based on a person’s health status and contacts with people who have tested positive for the virus. Only those with a green code can move around freely; reds are restricted. Complaints about the lack of transparency and the inability to appeal decisions are rampant on social media. In Hangzhou, where the app was developed by Alibaba Group Holding Ltd., officials have said they are looking to adapt and expand its use after the pandemic ends.

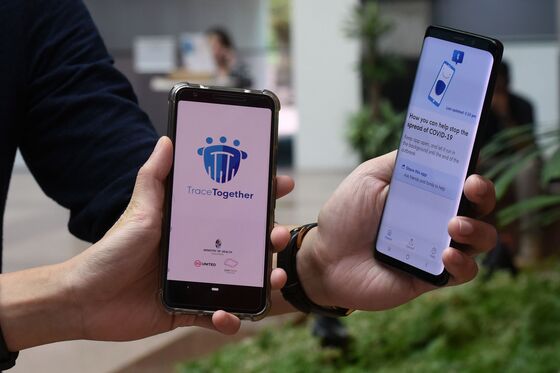

Some governments are skirting privacy issues by making contact-tracing apps voluntary. In Singapore, 1 million people, about one-sixth of the population, downloaded TraceTogether in 10 days after it was released last month. The government-designed app uses Bluetooth, enabling phones to link to each other when in proximity and keep a record of the contact. If a person tests positive, he or she can agree to release the data for the previous 14 days to public health officials so they can notify the contacts.

Singapore authorities say they can access TraceTogether data only if the user permits, and it will be erased after the pandemic is brought under control. Even one of the most ardent privacy enthusiasts in Singapore, who uses the Twitter handle Wai Sing-Rin, said he trusted that the government wouldn’t access his phone data unless he gives permission. “I’m an extreme case for privacy,” Wai said in a text message, “but for this, I jumped on it. It’s about protecting our society.”

Still, privacy concerns have come up. A group of volunteers working on a contact-tracing app in partnership with Stanford University says Singapore’s app is susceptible to attack because it could allow third-party tracking of Bluetooth IDs. And a coder posted a line-by-line analysis for TraceTogether on GitHub, a site that hosts a community of developers, saying he found pointers in the code to a government data-collection platform, raising the possibility that authorities were logging the data without permission. The developer then posted that he had reached the app’s designers and got them to agree to fix the flaw in an update.

In the U.S., companies including Palantir Technologies Inc., which has worked for intelligence agencies, have been in talks with government officials about using their tools to fight the pandemic. Palantir’s software, which is also being used by European nations, can help predict the locations of outbreaks and help determine where to deploy medical staff and supplies. Big data companies such as Unacast Inc., using publicly available anonymized location information from apps that users have already downloaded to their phones, have developed social distancing scoreboards showing how much Americans are moving around in defiance of government recommendations.

Such monitoring drew the attention of the European Data Protection Board after officials in Italy’s Lombardy region admitted they could see that residents’ movements far from their homes had dropped by less than 60% during the lockdown, based on data from cell towers that picked up pings from mobile phones.

While the board said the practice was permitted, Italian government officials have sought guidance from the European Union about whether they can use the data to track individuals who test positive for the virus, so they can alert people with whom they’ve been in contact. On a private conference call last month that included Italy’s prime minister and other European politicians, researchers and scientists argued that contact-tracing apps were dangerous and anti-democratic, according to a person familiar with the discussion who asked not to be identified because he wasn’t authorized to speak.

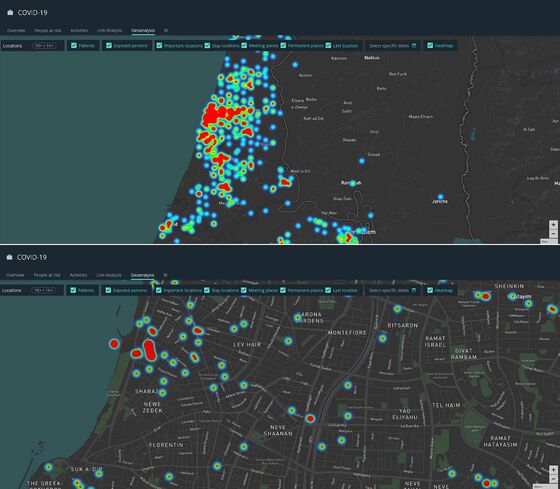

In Israel, a country known for using surveillance to counter terrorism, there was less caution about deploying contact-tracing technology. The domestic security agency, Shin Bet, was given the job of monitoring the movements of coronavirus patients through their mobile phones. But some civil rights groups took the matter to court. Despite assurances by Shin Bet chief Nadav Argaman that only a “very limited group” of agents would have access to the data, Israel’s High Court ruled in late March that Shin Bet could only go ahead with parliamentary oversight.

Since then, Shin Bet has started tracking location data from Israeli mobile phones to pinpoint anyone who might have come in contact with someone with the virus. In the last week of March, the organization sent text messages to more than 500 potential carriers, putting them into quarantine, a method more efficient than relying on patients’ own accounts of their whereabouts. The Health Ministry also released a voluntary app, ostensibly to back up Shin Bet efforts, to inform people if they have come in contact with an infected person.

A spokesperson for Shin Bet said the agency isn’t infiltrating mobile phones, but that hasn’t allayed the concerns of critics such as Tehilla Shwartz Altshuler, head of a program on democracy in the information age at the Israel Democracy Institute in Jerusalem. “Who will promise,” she asks, “that after this is over, we won’t become a surveillance democracy?”

An Israeli tech company, NSO Group Ltd., which developed the controversial Pegasus mobile-phone spyware, says it is testing a program for tracking potential virus carriers in a dozen countries in the Middle East, Eastern Europe, Southeast Asia, and South America. The system, initially developed for counterterrorism, uses algorithms and government-provided data to better allocate the distribution of testing kits, which are in short supply. The company won’t say whether the technology is being used in Israel.

“Allowing the use of technological tracking is a brave and unpopular decision, but I am convinced that in times of crisis such as the present, it is the right one,” says NSO Chief Executive Officer Shalev Hulio. “Proven technologies must be used to deal with pandemic and save lives. It is the hour, and it is necessary.”

Concerns about government overreach have also been raised in Hong Kong, where police are still cracking down on anti-government protesters. After authorities imposed new social distancing regulations on March 27, police began entering restaurants to make sure owners were keeping tables 1.5 meters (5 feet) apart and allowing only four people per table. At one restaurant owned by the son of a prominent dissident, they took the names and IDs of patrons, Apple Daily reported. The government has said such enforcement measures are necessary to stem the virus.

“We always worry a pandemic would lead to people accepting a surveillance authoritarian society,” says civic activist Galileo Cheng, who warned in a Twitter post that police would use social distancing regulations to target pro-democracy restaurants. “Now we are in Phase One of implementing Draconian laws.” —With Gwen Ackerman, Sohee Kim, Vernon Silver, Alessandra Migliaccio, Faris Mokhtar, and Lizette Chapman

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.