American Cities Brace for a Future With Even Greater Inequality

Cities were once escalators to opportunity, but changes in technology and other factors have reduced upward mobility. .

(Bloomberg Businessweek) -- There’s a debate raging among urban experts over how much the Covid-19 pandemic and recession will hurt American cities. Some predict heavy damage, whereas others foresee minimal harm. But cities are really just people. The right question: What will happen to New Yorkers? Angelenos? Houstonians? Detroiters?

On that question, there’s something closer to agreement: The virus and the economic slump are likely to worsen inequality, leaving the rich largely unscathed while crushing the poor and working classes of America’s big and midsize cities. That’s despite the efforts of Black Lives Matter and other movements that are devoted to fighting a winner-take-all urban economic system.

Since 2010 the population of 25- to 34-year-olds living within 3 miles of a city center has risen 30% nationwide, going up in every metro area with 1 million or more people, calculates Joe Cortright, an economist and the director of City Observatory, an urban policy think tank in Portland, Ore. “They’re the dream demographic of an HR department of a fast-growing company,” he says.

That trend is expected to continue. To narrow budget deficits, cities might have to cut back on social services that benefit mostly the poor and survive by enhancing their appeal to highly educated professionals, many of them young, say real estate executives, economists, and others who are tracking cities’ response to Covid-19. Those less favored will either move out or hang on by their fingernails.

Cities were once escalators to opportunity, but changes in technology and other factors have reduced upward mobility. Edward Glaeser, a Harvard economist who studies cities, says the pandemic will make it harder for cities to generate the kinds of jobs that low- and middle-skilled workers are qualified to fill.

Richard Florida, an urban economist at the University of Toronto, says he hopes cities will become more equitable because of policy innovation and new multiracial coalitions for justice. But right now, he wrote in Bloomberg’s CityLab in June, “we are experiencing a new urban crisis of ‘success’ marked by rampant unaffordability, third-world levels of inequality, and racial and economic segregation.”

Municipal finances are the heart of the problem. Most cities are required to balance their operating budgets, borrowing only for long-term projects such as construction. With $150 billion of federal aid through the Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security Act set to expire at year’s end and state governments unable to help much, mayors and councils are desperate to deal with shortfalls in sales taxes and user fees. Property tax revenues have held up so far, but they could drop once owners of real estate that’s fallen in value challenge their assessments.

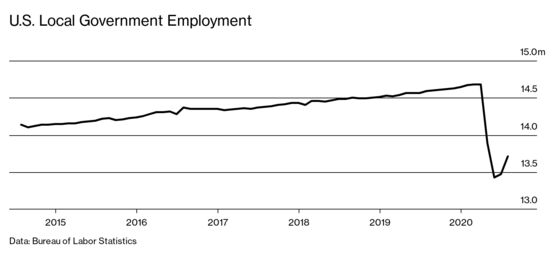

A third of cities have begun to cut municipal workers, and almost half plan hiring freezes, according to the National League of Cities, which estimates that the pandemic will leave cities with a $360 billion budget shortfall through 2022. In June the city council of Nashville raised property taxes 34%. Seattle and the District of Columbia have raised taxes on businesses. Chicago Mayor Lori Lightfoot and other Illinois mayors of both parties signed a letter in July to the state’s congressional delegation saying, “We cannot continue to function and serve the people” without more federal aid. “The irony is that the person who will defund the police is Donald Trump,” Dayton Mayor Nan Whaley told the Associated Press for an article published on Aug. 10.

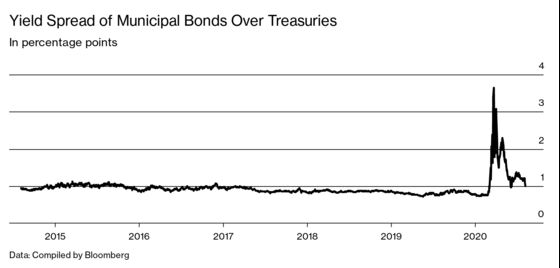

Pressure from Wall Street is a factor. Rather than one-off budgetary gimmicks, bond investors and ratings companies want to see lasting, “structural” budget changes. That’s often a euphemism for cuts in city jobs, many of which are held by residents of limited means. Investors appear confident that they’ll get what they want, though: After a sharp decline in the spring, mutual fund flows into municipal bonds have been strong. According to data gathered by Bloomberg, the yield on AAA muni bonds is only 1 percentage point higher than the yield on U.S. Treasuries, down from as much as 3.5 percentage points in the spring. That’s a sign investors are confident that cities—eager to avoid damage to their credit ratings—will find a way to keep paying, no matter how bad their situation.

Tax increases are an alternative structural remedy, but city governments shy away from them because they’re unpopular. Moreover, cities that have income taxes, such as New York, worry that higher rates will drive away top earners.

Telecommuting, which the pandemic necessitated, makes it easy for people to keep a city job while living in a cheaper suburban or rural home. Cities can overcome that disadvantage by continuing to make themselves attractive places to live for young, free-spending professionals, as they have for decades. Issues that are liabilities to middle- and working-class families—such as deteriorating public schools and public transportation—are less of a problem for childless younger workers who have cars or get around by Uber or Lyft.

When maskless young people crowd into restaurants and clubs in U.S. cities, it’s simultaneously a serious risk factor for spreading Covid‑19 and strong evidence of the enduring appeal of the urban lifestyle. Cities snapped back quickly after the Spanish flu pandemic of 1918-20, and New York rebounded from the terror attack of Sept. 11. “I keep hearing about how cities are going to die because of one or another phenomenon, but it never happens,” says former New York City Planning Commissioner Alex Garvin.

Tech companies continue to put offices in Manhattan because that’s where their employees and potential recruits prefer to be: Facebook Inc. this month leased more than 700,000 square feet in an iconic building facing Penn Station, adding to other leases and making the company one of the city’s biggest corporate tenants.

It’s considerably less dreamy at the bottom of the income scale. About 29% of renters in households earning less than $50,000 a year say that the pandemic has made them more likely to move and that they’re “primarily motivated by a need to secure stable and affordable housing in the face of financial uncertainty,” according to a study by Apartment List Inc. Consulting company Oliver Wyman, in its research for the Partnership for New York City, estimates that the shortage of affordable units in the city will rise 17%, to 760,000, by next April. A four-month federal moratorium on evictions expired in July, and Congress is deadlocked over how to renew it. That puts a fifth of the 110 million Americans in rental housing at risk of eviction by the end of September, according to the Colorado-based Covid-19 Eviction Defense Project.

“There really is a crisis under way in the rental market,” says Jeff Tucker, a senior economist at Zillow.com Inc. Owners are less stressed than renters on average, he says: Demand for purchases has stayed strong “because homebuyers think on a five-year scale”—that is, they’re focusing on a brighter post-pandemic future.

What’s new is not only the pandemic but a change in Washington’s attitude toward cities. Richard Ravitch, who was involved in the talks that led to the Ford administration’s bailout of New York City in 1975, says, “What’s going on today is not in any way analogous to what happened then.” That’s partly because the problems are more serious, he says, and partly because “we have a total, incomprehensible lack of government leadership.” Although born a New Yorker, Trump draws most of his support from rural areas and suburbs. “It’s a shame to reward badly run, radical-left Democrats” who run cities, he told reporters on July 30.

With cities left pretty much on their own to cope with Covid-19 and double-digit unemployment, their financial survival is at stake—and lessening inequality and injustice may be falling down the list of priorities.

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.