Convenience Stores Turn to Home Delivery to Fight Pandemic Slump

Convenience Stores Turn to Home Delivery to Fight Pandemic Slump

(Bloomberg Businessweek) -- America’s 152,000 convenience stores survived—even thrived—during the Amazon era by being the quickest way to buy things like ice cream and cigarettes. They mostly ignored the web because they could, thanks to their ubiquitous presence on urban street corners and suburban roadways.

The coronavirus is quickly challenging that business model. Since the pandemic hit the U.S. in March, drastically reducing in-store shopping, big players like 7-Eleven, Circle K, and Casey’s General Stores have accelerated the rollout of delivery from thousands of locations via third-party platforms such as DoorDash, Postmates, and Uber Eats.

“What Covid really did is it gave the industry a peek into the future,” says Frank Beard, a retail consultant. Convenience stores were eventually going to face the same challenges from e-commerce specialists that have already crushed department stores and apparel chains. The pandemic sped up that timeline, however, as Americans grew wary of going to public places and spent less time driving because they’re working more from home. “Covid disrupted some of these routines,” Beard says, “and there’s going to be a lot of lingering effects.”

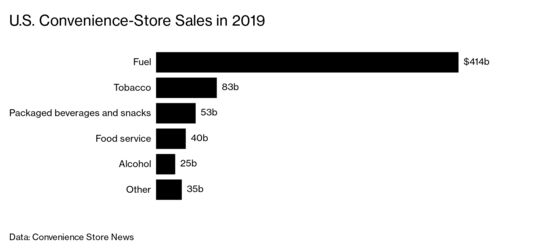

The industry has been a rare success story in brick-and-mortar retailing by improving its food and beverage offerings—especially coffee—thereby increasing sales and customer visits. Regional chains such as Wawa, Sheetz, and Casey’s elevated the convenience-store menu from being a punchline on The Simpsons into a dining destination for many time-pressed consumers. Selling higher-margin beer and slushees also evens out the volatility of selling gasoline, which accounts for about two-thirds of the industry’s revenue but just 40% of its gross profit, according to Convenience Store News.

Even before the pandemic, the volume of gasoline sold at the stores annually had been declining slightly in recent years. Now the reduced demand for fuel, induced by Covid, means boosting sales of on-the-go food and general merchandise is even more important for the industry, which saw annual nonfuel revenue grow 10% over the past four years, to $235 billion in 2019. But the coronavirus has pushed other types of retailers to dive into e-commerce, promising the quick service that had always been the raison d’être of convenience stores.

Grocery stores have ramped up Instacart offerings, mom and pop stores signed up with delivery apps, and restaurant chains poured money into online takeout menus. Amazon.com Inc. meanwhile is expanding one-hour delivery, which in some markets includes convenience items like soda and razors. And in August, DoorDash Inc. debuted an online convenience store called DashMart that promises to offer thousands of items for delivery in less than 30 minutes from its own distribution centers. The delivery giant has started the service in eight cities, including Chicago and Phoenix, and plans to add more locales soon.

Convenience-store operators are offering a wide range of home-delivery items, everything from milk, eggs, and Ding Dongs to Tylenol and coffee filters. But serving customers online brings its own challenges—especially if it narrows stores’ already thin margins because of the added cost of getting goods to shoppers’ doorsteps. “There is this growing pressure to explore delivery, but delivery is tough,” says Jennifer Bartashus, an analyst for Bloomberg Intelligence. “In the short term, it meets a need for customers who don’t want to come into stores, but there are questions about long-term profitability.”

John Nelson, who founded Vroom Delivery, which offers stores an e-commerce platform, says outsourcing delivery will eventually become too expensive or it will lead to price increases to make up for the cost. Plus, many states forbid third parties from delivering lucrative items like tobacco and alcohol; that could push convenience stores to hire their own employees to make deliveries to homes. “Even the big chains are going to have to reevaluate their distribution models,” Nelson says.

There’s also the dilemma that the better a store’s online offerings become, the more customers may skip the shopping trip to a brick-and-mortar outlet. That often causes a hit to sales, because it eliminates impulse purchases that in-store merchandising is still very good at generating.

To improve results, e-commerce veterans use data science and algorithms to increase online order size. But convenience stores start at a disadvantage, having an average total purchase of just $9, according to Convenience Store News, and now they have to give a cut to delivery apps. Delivery services charge 15% to 30% of a convenience purchase’s bill—plus fees paid by the customer, which can double the price of a small order. But if stores are going to remain convenient in the eyes of shoppers, they don’t have much choice. “Consumers are being trained for instant gratification,” Bartashus says. “It’s hard to see that changing anytime soon.”

Convenience-store chains have tried to ease investor concerns by pointing to early signs that online customers are spending more per purchase, especially after 9 p.m., when few people want to venture out. Some have said delivery expansion hasn’t cannibalized in-store revenue, but is instead generating a net sales boost that, even at a smaller profit margin, will make them more money.

In the Midwest, Casey’s had been using its own drivers to mostly deliver pizza, its most popular food offering. When the crisis hit, it was testing DoorDash in 30 stores to offer longer hours and more items, according to Chris Jones, chief marketing officer. Within weeks, the pilot expanded to 600 stores. The company said it isn’t worried about Amazon, because half its locations are in towns of fewer than 5,000 people—parts of the U.S. where the e-commerce giant doesn’t yet offer speedy delivery. “We’ve got a real advantage based on our physical locations,” which allow Casey’s to make the vast majority of deliveries within 45 minutes, Jones says.

Speed, a skill convenience stores have mastered at physical locations, will no doubt be a key factor. Customers spend an average of just three or four minutes from the moment they exit their car to when they leave the store, according to the National Association of Convenience Stores. Operators are intent on maintaining that timing advantage as they move online.

In Reston, Va., a Bloomberg reporter recently used 7-Eleven’s app to order a large, cooked pepperoni pizza and a Coke slushee totaling about $12, including tax and fees but excluding tip; it was delivered by DoorDash 36 minutes later. Across the country in San Francisco, a 7-Eleven online order of a cooked chicken breast in a ready-to-heat package, milk, and a banana for about $9 arrived via Postmates in 18 minutes. Both times easily beat those promised by grocery stores and Amazon, which has seen its own delivery times slowed because of the surge in pandemic-era demand.

7-Eleven, the largest U.S. chain, which will have more than 13,000 stores in America after completing its acquisition of Speedway convenience outlets from Marathon Petroleum Corp., is going all-in on home delivery. A year ago it offered the service in 200 U.S. cities. By mid-August, it was scheduled to have delivery in 1,300. “The definition of convenience has rapidly evolved during this pandemic,” says Chris Tanco, 7-Eleven’s chief operating officer. “Delivery expansion is here to stay.” —With Nic Querolo and Edward Ludlow

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.