A Decade’s Worth of Progress for Working Women Evaporated Overnight

A Decade’s Worth of Progress for Working Women Evaporated Overnight

(Bloomberg Businessweek) -- Ashley Reckdenwald loves her job. But the reality of the pandemic is that someone has to stay home with the kids.

Reckdenwald, a physician assistant in Princeton Junction, N.J. is among the 23.5 million working moms with kids under 18 years old that make up almost a third of the female labor force in the U.S. After the pandemic shuttered schools and child-care facilities in March, she faced the painful decision of prioritizing her children over her career.

“I knew I had to put my kids first and my career on hold, but it’s like this pandemic is forcing women 10 steps back,” says Reckdenwald, who was in the process of switching jobs when the pandemic hit.

With child care expected to remain scarce, at least through the summer, Reckdenwald, 36, decided to stop interviewing for jobs in order to stay home with her three children, ages 5, 2, and 10 months. Her husband, an engineer, works at a marine construction site and is the primary breadwinner, so the move made sense, but Reckdenwald fears that an additional break from the workforce could hurt her long-term earning potential, not to mention her peace of mind. “Working fulfills me, helping me keep perspective and prioritize,” she says. “I like the example it sets for my children when I talk about my day and the people’s lives I touched.”

The pandemic has already ushered in the highest unemployment rate since the Great Depression. Last year, women made up the majority of the U.S. workforce for the first time in almost a decade. In March and April, they accounted for 55% of the job losses, and more than that in female-dominated sectors such as retail, travel, and hospitality, according to the Institute for Women’s Policy Research, a Washington think tank.

Men have not been spared the pain of the pandemic, but preliminary research suggests women have been impacted disproportionately. They are losing jobs at higher rates than men, represent a greater proportion of hourly workers that don’t have paid sick leave, and are shouldering most of the additional housework and child-care duties, according to an April survey of 3,000 people conducted by Lean In and SurveyMonkey.

Even as cities and states lift lockdowns, working moms say they have no choice without sufficient child-care options other than to scale back their career ambitions, leave the workforce, or sacrifice their sleep and mental health to juggle work and full-time child care at the same time.

Since women earn about 80% of what men do, they are often the ones who end up having to make career sacrifices among dual-income, heterosexual families. Economists and labor rights advocates say those decisions could result in a catastrophic setback for women.

“Families make tough decisions when it comes to who’s going to care and provide for the family in the pandemic—and in many cases, maximizing household income means the woman stays home,” says C. Nicole Mason, chief executive officer of the Institute for Women’s Policy Research. “Couple that with the disproportionate impact of job losses on women during this pandemic, and it could have a devastating economic impact on families, as well as women’s long-term earnings and career advancement.”

In the 2008 recession, the hardest-hit sectors were male-dominated industries such as construction and housing. During the recovery, says Mason, many working moms went back to school or trained in new fields to boost their earning power. That option isn’t available to many women now that child care is curtailed.

Mason says U.S. policymakers and companies now face a choice: Give up the hard-fought gains among working women, or use the pandemic to formalize policies that could help engender an equal recovery, including paid sick leave, flexible working arrangements, and child-care support.

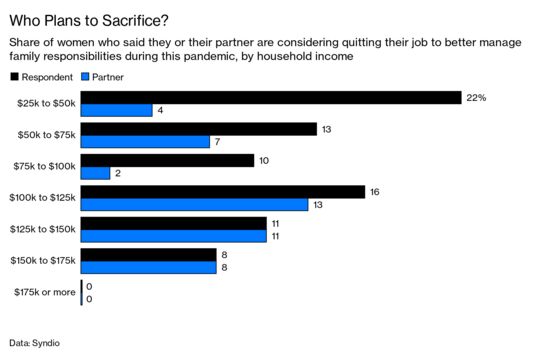

By March, 14% of American women who work full-time and have children at home were already considering quitting their jobs to take care of their families. That compares to 11% of men surveyed by Syndio, a company that develops software for corporate human resources departments.

Social media feeds may be filled with smiling photos of working moms baking bread and crafting with their kids between Zoom meetings. But women are typically spending 20 more hours a week on housework and caregiving than men in the same situation do, the Lean In survey found, noting that women of color and single mothers are putting even more hours.

“The pandemic amplified an already untenable situation, where women are burning the candle at both ends as they drown in work and hack together child care,” says Alexis Barad-Cutler, who runs an online women’s community called Not Safe For Mom Group and has two sons, age 6 and 8.

“Working moms are already earning less to the dollar than our male counterparts and now, because we’re not the higher wage earners, our careers are put to the side again,” says Barad-Cutler, who took charge of home schooling because her husband, an attorney in New York, is the primary breadwinner. She now takes care of her kids during the day and works from 9 p.m. to 1 a.m. most nights.

Many women don’t have an option to scale back. There are 15 million women in the U.S. whose paychecks amount to at least 40% of their household income, according to the Institute for Women’s Policy Research. That means half of all mothers in America with children under age 18—and four out of five black mothers—are breadwinners.

Kai White, a single mom in Long Beach, Calif., says school closures and the inflexibility of her job has left her in a suffocating spot: “Either neglect my kids and their schoolwork, or risk being fired.”

White, 31, is a job recruiter at a staffing company with 200,000 employees. Considered an essential business, the company hasn’t halted in-person recruiting events. White says she’s on a salary, but she is evaluated, in part, on how many people she hires. After using her paid time off, she says she has had no other choice but to ask for an unpaid leave of absence. Since her employer allows only 30 days of personal leave, she had to return to her job on June 1.

“I'm panicking,” White says. “I need money for rent and food, but I also can’t risk contracting the disease or leaving two toddlers at home with my 12-year-old.”

In March, Congress passed legislation that affords 12 weeks of paid leave for parents whose school or child care provider is closed in response to Covid-19. Companies with more than 500 employees are exempted.

“These companies were given a loophole under the assumption they already had measures in place to deal with medical leave,” says Daphne Delvaux, a senior trial attorney at Gruenberg Law in San Diego. “But it’s not happening, because it’s a leave for school closures, which doesn’t exist in company policies. I’m hearing stories from women staying up all night working, just to keep their jobs. One client was laid off at 39 weeks pregnant. Her company blamed it on the pandemic, but she was the only one laid off.”

Employees can take 12 weeks of pandemic-related parental leave at Microsoft Corp., 14 weeks at Alphabet Inc.’s Google, four weeks at Facebook Inc., and 10 days of caregiver leave at Goldman Sachs Group Inc.

But even though two in five families in the U.S. have children under the age of 18, almost 60% of workers say their employer hasn’t changed policies to offer more flexibility, according to the Lean In survey.

“That’s the starkly sexist part of this virus,” says N. Leahy, a 31-year-old events planner who lives in Rhode Island and was the main breadwinner in her family before the pandemic hit. “It forces decisions about which part of your identity is going to win out, parent or employee.”

Leahy had planned to return to work in June after taking maternity leave for her second child’s birth in February. Now, her boss doesn’t know if her job will still exist. Leahy also isn’t sure she wants to go back, worrying that “workers with kids will be penalized if they don’t want to take health risks like going into the office and sending their kids to day care.”

As job losses mount around the country, Leahy says many of her friends fear losing their jobs if they admit to their employers that they’re having a hard time. “I've been struck by the level of anxiety and desperation I’m seeing in the closed Facebook groups—and hushed conversations that I don’t see on the Today show or Instagram posts advising yoga and productivity journals,” she says.

For now, Leahy says her family will be able to survive off her husband's income “by the skin of our teeth” but that the long-term consequences could be devastating for women such as her. “We know the choice has to be our children, but that doesn’t make it any easier or less painful for us individually, or for the economy and society as a whole.”

Read next: Seattle Bar Owner Says the Crisis Is Different for Older Entrepreneurs

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.