Companies Use Borrowed Billions to Buy Back Stock, Not to Invest

Companies Use Borrowed Billions to Buy Back Stock, Not to Invest

(Bloomberg Businessweek) -- When the Federal Reserve cuts interest rates, making it cheaper to borrow, it’s supposed to deliver a direct boost to the economy. But one key part of that machinery has broken down.

Business investment used to rise when U.S. companies took on more debt—because most companies borrowed to add capacity. Nowadays, they’re likelier to funnel the money to shareholders.

Investment is stuck at low levels by historical standards. President Donald Trump’s reduction in corporate taxes hasn’t changed the pattern. Neither has a decade of low interest rates, even before the Fed’s quarter-point cut on July 31.

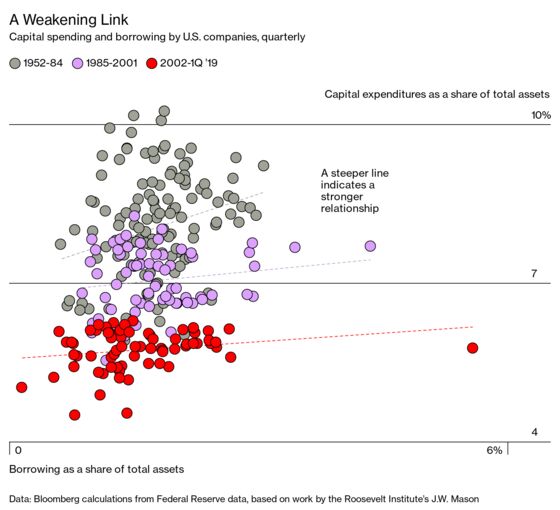

It’s not that business stopped borrowing. As a share of gross domestic product, corporate debt has climbed to a record. What’s all but vanished is the correlation between how much companies borrow and how much they invest.

That long-standing relationship endured, albeit weakened, through the 1980s and ’90s as companies focused increasingly on driving shareholder value, says J.W. Mason, a fellow at the Roosevelt Institute in New York who’s been researching the topic. Now it’s gone, and Mason says the data suggest a different link. “If you can borrow on more favorable terms, you don’t necessarily invest more,” he says. “You might think this is an opportunity to give bigger payouts to shareholders. This is a big reason why monetary policy isn’t as effective as it used to be.”

Companies can return money to investors through share buybacks and dividends. Cash payments for acquisitions fit the category too—at least for an economist looking at the macro picture rather than at individual companies—because they’re another transaction where money goes to holders of already-existing assets.

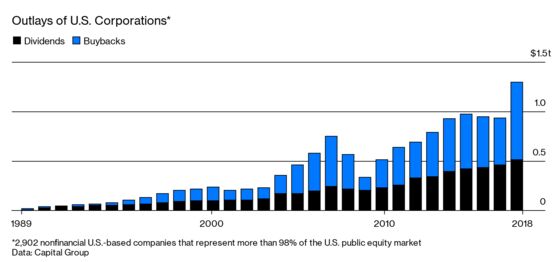

Buybacks, in particular, have become a controversial way for businesses to spend. They took off in the U.S. after 1982, when a U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission ruling reduced the risk that they’d trigger charges of market manipulation. Buybacks are likely to approach $1 trillion this year, according to a Goldman Sachs Group Inc. forecast, rising from 2018 levels that were already a record.

The finance industry defends the practice, arguing that outsiders shouldn’t be second-guessing corporate managers who have the best handle on where they can usefully channel funds. If those managers can’t see opportunities for profitable investment, in other words, maybe there aren’t any.

Still, buybacks are in the political spotlight. On the Democratic side, Senators Chuck Schumer and Bernie Sanders have called for curbs. Republican Senator Marco Rubio has criticized the tax code for encouraging buybacks over investment.

Dan Ivascyn, group chief investment officer at Pacific Investment Management Co., says the economy can benefit in “indirect ways” when companies borrow at low rates to finance buybacks and dividends, as those activities typically boost the price of a stock. For owners of those shares, there’s a wealth effect—which may induce them to spend more. There’s also a dynamic in which “higher stock markets improve business confidence,” because they’re widely viewed as a gauge on the outlook for the economy, says Ivascyn.

That’s pretty much the line Fed Chair Jerome Powell took at a July 31 press conference, after the Fed’s first interest-rate cut in a decade. Asked how cheaper borrowing can help the real economy when the cost of capital doesn’t appear to be an issue for business, he said the policy “seems to work through confidence channels, as well as the mechanical channels.” That confidence has lifted asset prices to record highs—though it doesn’t seem the kind that gets business to invest.

When economists search the horizon for the next source of trouble, they often alight on corporate debt. It’s true that American companies aren’t the biggest borrowers in the low-rates era that began in 2008. That would be the federal government. But the government controls the dollar printing press, so it can’t really go bust. Plus, there hasn’t been a sovereign debt default in a rich country for decades.

Analysts at Capital Group, a Los Angeles-based investment firm, have concerns about debt-financed buybacks and dividends. That kind of spending has jumped above a key cash flow measure, they found. “We’re trying to identify those companies that, in this late cycle, might not have used debt for the primary purpose of growing the business,” says David Bradin, a fixed-income investment specialist at Capital Group.

Companies that borrow to increase capital spending or for acquisitions will have more options to pay off debt in a downturn. It’ll be easier for them to pare back operations or “potentially sell noncore assets to pay off some of the debt,” Bradin says. Companies that borrow to fund buybacks and dividends may not have those resources to draw on.

While bond pickers like Bradin look at the risks for individual businesses, economists such as William Lazonick, a professor at the University of Massachusetts at Lowell, worry that buybacks, debt-financed or otherwise, are bad for the whole economy. Lazonick has campaigned against the practice for decades. It’s often been a lonely fight—but less so lately. He advised Hillary Clinton when she was running for president in 2015 and has been consulted by Sanders. Rubio cited his work this year in a report on America’s failure to invest.

Lazonick says buybacks are a driver of high inequality and low investment. They’re also a reason U.S. companies have fallen behind their Chinese competitors in the race to dominate 5G telecommunications. (He’s working on a paper comparing Huawei Technologies Co. with Cisco Systems Inc., which has spent more than $100 billion this century buying its own stock.)

Most economists, blinded by faith in financial markets as the most efficient allocators of resources, have missed the whole problem, according to Lazonick. “They just say, ‘Oh, the investment ends up somewhere,’ ” he says. “That’s an argument with no evidence.” Lazonick says the label favored by corporate bosses to describe their buybacks—“capital return program”—is misleading. “Capital is something that gets invested,” he says. “It’s not capital. It’s just money.” —With Alex Tanzi

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Cristina Lindblad at mlindblad1@bloomberg.net

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.