In the Fog of Pandemic, Companies Are Embracing Epidemiology

In the Fog of Pandemic, Companies Are Embracing Epidemiology

(Bloomberg Businessweek) -- On the last day of February, when health officials in Washington state announced some of the earliest known Covid-19 cases in the U.S., a Microsoft Corp. executive emailed officials at the King County health department to ask for help. Seattle business leaders were meeting the next day, and “they would like someone that can best speak to what businesses should do,” wrote Colleen Daly, a senior benefits executive. In a follow-up the next morning, she wrote that companies were “spinning on” questions of whether to cancel events, restrict travel, or send workers home. “Since this is an emotional situation we are seeing businesses struggle to stay grounded,” she wrote.

It was an early brush with a problem now vexing companies everywhere: how to understand and respond to a new world of risks that most businesses have never encountered. Executives who’ve been around for a while have already had to learn how to steer their businesses through terrorist attacks, natural disasters, and financial crises. But no one alive today has ever before had to deal with this species of global calamity. It’s forced shutdowns of entire economic sectors, scrambled supply chains, and— at least in the U.S.—shown no sign of abating.

The chaos is compounded by a kind of fog of war that’s made it almost impossible for managers to know where to turn for reliable information. Public-health authorities have been caught up in the politicization of crucial questions such as when to impose or lift restrictions. With a lack of clear guidance from the federal government and with states and local governments setting their own sometimes conflicting policies, companies face a bewildering tangle of inconsistent rules and guidelines. And they’re forced to figure out how to protect their employees’ and customers’ health while still attempting to turn a profit.

Some are better equipped to do that than others. At pharmaceutical giant Bristol Myers Squibb Co., David Shepperly oversees the well-being of 30,000 employees spread around the globe. His job as the executive director for occupational health was radically transformed in the aftermath of the January novel coronavirus outbreak in China. He moved quickly to impose quarantine rules and travel restrictions for the company’s more than 1,400 employees in the country.

Shepperly, a physician who also has a master’s of health sciences degree in biostatistics from Johns Hopkins, mobilized a team of scientists and analysts to monitor data around the globe on new cases, hospital capacity, and local guidance. They developed criteria for which circumstances would trigger escalating levels of restrictions.

They made the call on March 13: More than 250 of Bristol Myers’s sites around the world would go into what Shepperly calls the “red phase”—only the most essential manufacturing staff could remain. It was six days before the U.S.’s first statewide stay-at-home order in California.

The timing for reaching the “green” phase of normalcy remains “the big question,” Shepperly says. Bristol Myers, which consults with occupational health teams at other leading drugmakers on a weekly basis, lets the data drive its decisions. “Everything we’ve done to protect our employees is based on the science of Covid,” he says.

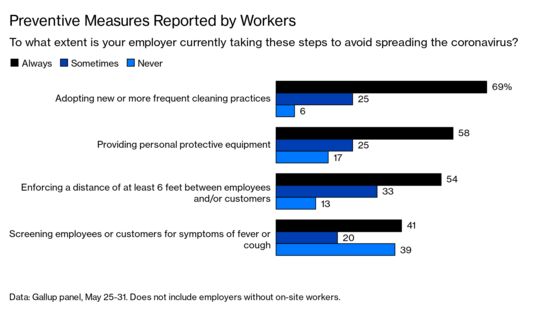

Many companies don’t have an in-house bench of medical experts and data scientists to guide their reopening decisions. They rely on authorities and outside advice to determine what precautions to take—and how to minimize the risk of litigation if workers or customers blame the business for exposing them to the virus. The U.S. Chamber of Commerce and other business groups have lobbied Congress to protect businesses from Covid-19-related lawsuits. The chamber has also called for “uniform guidelines that can be practically implemented” as states reopen.

So far, that hasn’t happened. Instead there’s a patchwork of federal, state, and local rules that companies must sort out. In early July, for instance, Kansas ordered people to wear masks in public if they can’t keep 6 feet apart. Across the border in Missouri, there’s no statewide mask rule, but St. Louis requires them. Apple Inc. shut its retail stores in Arizona, the Carolinas, and Florida on June 19 as case counts rose. That was about a week before governors dialed back their reopening plans. AMC Entertainment Holdings Inc. initially said masks would be optional when its movie theaters reopen, but a swift backlash prompted the chain to backtrack.

Wary of missteps, companies are turning to consultants and academic experts for guidance. “The appetite for the information is huge,” says Mike Van Dyke, an associate professor at the Center for Health, Work & Environment at the Colorado School of Public Health. The center began doing weekly webinars for businesses related to Covid-19 this spring that attracted at least 200 attendees each, compared with the 40 or 50 who typically attended the group’s online events before the pandemic.

Businesses are also hiring more hands-on help. Van Dyke, consulting directly with employers, has advised them on such questions as how high plastic barriers should be, whether employees should sit back-to-back, and what kind of changes to the ventilation system might reduce the risk of spreading viral particles. The advice he gives is grounded in science, but few of the interventions have been tested in practice.

Van Dyke did some early work with meatpackers trying to minimize exposure in the absence of clear instructions from regulators. “At that point there was really a big void. There wasn’t much guidance out there,” he says. While agencies have begun to catch up, employers still want assistance putting official guidelines into practice. “There’s a lot of ‘You should do this in general,’ ” he says. “But there’s not much ‘This is how you do it.’ ”

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.