Corruption Sinks a Nation and May Turn a Comedian Into President

Corruption Sinks a Nation and May Turn a Comedian Into President

(Bloomberg Businessweek) -- There’s nothing funny about why a comedian is getting a shot at becoming president of Ukraine, a country at war.

In dramatic revolutions of 2004 and 2014, Ukrainians have twice sought to buck a political system in which wealthy oligarchs appeared to take turns milking the state. Both attempts to root out systemic corruption are widely seen as failures, despite a new antigraft agency and sweeping bank cleanup.

Faced with familiar candidates who seem to offer more of the same—the near-billionaire incumbent, Petro Poroshenko, and former prime minister and onetime natural-gas mogul Yulia Tymoshenko—voters appear to be turning to the absurd. Television comic Volodymyr Zelenskiy, whose show Servant of the People takes aim at a hated elite, is leading opinion polls ahead of the March 31 election.

From allegations of politicians being bought to violent attacks on activists and suspect trials, the impact of kleptocracy on Ukraine is hard to overstate. A well-educated nation of 42 million with a fertile landmass the size of France now threatens to displace Moldova as Europe’s poorest.

Rampant graft has left Ukraine unattractive to investors and vulnerable to Russian manipulation at a time of rising tension between Moscow and the West. Money from the former Soviet Union allegedly being laundered in European and U.S banks has attracted international scrutiny.

Patience among the country’s backers is running thin. The U.S. last week called for the prosecutor in charge of anticorruption cases to be replaced and the system revamped. The demand came after a close associate of the president’s was embroiled in an arms embezzlement scandal. Poroshenko has since fired the individual, but the affair continues to undermine his election campaign.

A U.S. Department of State report published on Wednesday found that corruption remained “pervasive at all levels in the executive, legislative, and judicial branches of government.”

“It’s very difficult to impose from outside the fight against corruption, when the political elite works against it,” says Oleksandr Danylyuk, a former finance minister who helped put anticorruption reforms in place.

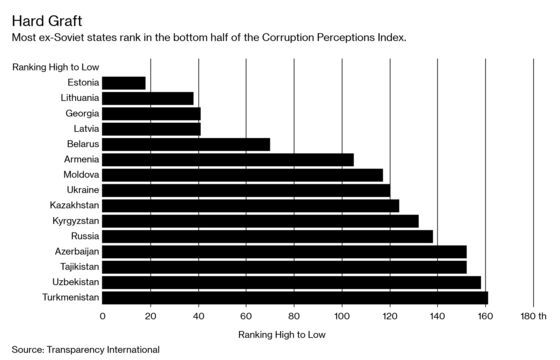

Ukraine ranks joint 120th of 180 nations in Transparency International’s annual corruption perceptions index, together with Liberia, Malawi, and Mali. It’s an improvement from a dismal 144th place in 2013.

All political parties in Ukraine pledge to fight corruption, and Poroshenko has overseen the adoption of more reform legislation than his predecessors. A new 85-page report assessing anticorruption efforts during Poroshenko’s presidency concludes that electronic tax collection, anti-money-laundering measures, and changes in the natural gas industry plugged a $6 billion or so hole in Ukraine’s annual budget, even if “the fight against corruption has only just begun.”

“I guarantee zero tolerance of corruption,” Poroshenko said in a television interview in March. “I guarantee that those who stole will be held accountable.”

Danylyuk, who was fired in June for complaining to Western ambassadors about the slow pace of change, describes a Sisyphean cycle of attempts he made to implement reforms the government adopted under pressure from the U.S., the European Union, and the International Monetary Fund. He says all he did was meet resistance from the president’s aides and supporters in parliament, long notorious for trading seats and votes for money.

Indeed, one businessman-cum-politician said he personally took bags of U.S. dollars down a narrow private elevator that leads from the waiting room outside Poroshenko’s office.

Oleksandr Onyshchenko, who says he was Poroshenko’s paymaster in the legislature until the two men fell out in 2016, says the bags were put in the trunk of his car, which he then drove to parliament to buy votes at a market price that ranged from $20,000 to $100,000 per legislator.

“They paid cash,” he said by video between his rounds in a Spanish horse jumping competition. “You’d come to the presidential administration garage, go up to the fourth floor, and take the bags, so no one could see.”

Poroshenko has vehemently dismissed the claims and called on Onyshchenko to return to Ukraine and face justice. The businessman fled the country in 2016, after being charged with embezzling tens of millions of dollars from a state-owned energy company. He says the case against him is politically motivated.

Nowhere better demonstrates the human cost of corruption than Odessa, a lively port city on Ukraine’s Black Sea coast where tourist attractions jostle cheek by jowl with newly established strip joints with names like Rasputin and Flirt Deluxe.

The last year and a half has seen an unprecedented spate of attacks on anticorruption campaigners. One was stabbed and another shot. Others were severely beaten. In August, lawyer Mikhail Kuzakon and journalist Grigory Kozma narrowly escaped being crushed when a truck plowed into their stationary car.

All the victims had sought to expose allegedly corrupt deals made or approved by the local authorities, headed by Mayor Gennadiy Trukhanov. Currently on trial for allegedly embezzling $6 million from the public coffers in the privatization of a building, he denies any wrongdoing.

“It’s theater,” Kuzakon says of the court system. After he posted a video last month, in which he accused Poroshenko of granting impunity and control of cities and regions to criminal groups in return for political support, police assigned Kuzakon a five-man protection detail. “If it were profitable to Kiev to convict Trukhanov, it would already have happened.”

The case against Trukhanov is evidence of new independent anticorruption institutions at work, Poroshenko’s office said in a written response. That infrastructure, built over the last five years, exists “thanks to President Poroshenko’s political will” and accusations to the contrary are politically motivated, the statement said.

The president’s office also accused Danylyuk, the former finance minister, of abandoning reform to work for Zelenskiy, who it said was supported by Igor Kolomoisky, a powerful oligarch anxious to recover assets lost in the cleanup of the financial industry. Zelenskiy’s show airs on the TV channel owned by Kolomoisky. The two men deny any political or financial ties beyond the TV contract.

In November, public pressure prompted the parliament in Kiev to create a temporary committee to investigate more than 50 similar attacks across the country in 2018, including murders.

Kuzakon’s skepticism has been deeply ingrained among Ukrainians since at least the 2000 release of Watergate-style tapes, purportedly of conversations in the office of Ukraine’s second president after the Soviet breakup, Leonid Kuchma.

The recordings, often foul-mouthed, included chatter about bribes worth tens of millions of dollars, as well as discussions of the need to silence an anticorruption journalist later found beheaded. Kuchma has denied the authenticity of the tapes and says recordings of his voice were edited into a pastiche.

Among those purportedly recorded offering bribes was Kuchma’s intended successor as president, Viktor Yanukovych. The estate Yanukovych built outside Kiev when he did become president in 2010, complete with an exotic car collection and zoo, has become a public museum intended to show the gaudy fruits of corruption.

When Yanukovych fled to Russia in 2014, Ukraine’s new leaders said they had identified $70 billion that he and his entourage had spirited to offshore accounts. Five years later, nobody has been charged with the thefts. Yanukovych has since denied stealing money or owning foreign bank accounts. He says the estate outside Kiev was not his personal property.

The best hope for Ukraine, says Vadim Morokhovsky, the 47 year-old chairman of Odessa-based Bank Vostok, is that there are now more young voters who never knew the Soviet Union and who don’t see corruption as an inevitable part of life.

Social media such as Facebook and Instagram are eating away at the control over information and election campaigns that Ukraine’s business clans still exercise through their domination of the press. That shift helps explain why the electorate is becoming more fragmented and less predictable, according to Morokhovsky.

Zelenskiy, 41, is a product of that change. The comedian, who also runs a production business with distribution across the former Soviet bloc, has said he might hire Danylyuk and other disillusioned reformers if he gets to form a government.

The latest polls give him a lead of between 5 and 10 percentage points over Poroshenko and Tymoshenko, though anything can happen. If, as expected, no one candidate wins a majority, the two that score highest will compete in a runoff in April.

Should Zelenskiy win, life would be imitating art. In his show, he plays an unsuspecting history teacher pushed by chance into the presidency. In one episode, he dreams of taking a machine gun in each hand and mowing down legislators in parliament.

In reality, Zelenskiy says he would work with the International Monetary Fund and introduce a capital amnesty under which businesspeople could legitimize hidden assets in exchange for paying a 5 percent tax. He also pledges to strip lawmakers, judges, and the president of their immunity from prosecution, and to make the courts free from political interference.

Savva Libkin, who owns eight restaurants in Odessa and Kiev, will take some convincing. He sees oligarchs with vested interests in the current system behind all three main candidates.

“I was born in a corrupt hospital, the nurse who delivered me was corrupt, and the gravedigger who buries me will be corrupt,” says Libkin. “This is a disease like AIDS that has mercy for no one, and the people who are fighting it stink of it.”

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Jillian Goodman at jgoodman74@bloomberg.net, Rodney Jefferson

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.