Backlash to Colombia Tax Reform Shows It’s Too Soon for Austerity

Backlash to Colombia Tax Reform Shows It’s Too Soon for Austerity

(Bloomberg Businessweek) -- In the predawn hours of May 10, Colombian President Iván Duque flew to the city of Cali to try to quell protests that had become violent and blocked key roads. It was the latest repercussion from a planned reform that’s become a political disaster for the government—and a warning sign for other countries.

After borrowing heavily during the pandemic, Colombia moved faster than many developing-nation peers to get its financial house in order, announcing a new tax reform bill on April 15. Duque promised it would trim deficits and help the poor by increasing the burden on middle-class and wealthy individuals at a time when the country’s poverty rate is surging. The measure, set to take effect in 2022, was meant to convey discipline and reassure investors. Instead, the blowback was fast and fierce: nationwide protests, more than 40 people dead, and the country’s finance minister out of a job.

The debacle brings lessons for other countries around the world that will eventually have to choose between funding their economic recoveries or tackling their deficits. Developing nations are especially under pressure to satisfy investors who demand fiscal prudence. “There will be similar bills to pay across Latin America and emerging markets,” says Jonathan Davis, a money manager for emerging-market debt at PineBridge Investments, which holds Colombian bonds.

Economists warn against pulling back too much stimulus, too soon. In Latin America, where the pandemic has thrown millions into poverty, the recovery is tenuous following a 7% economic contraction last year, the worst in two centuries. Tax reforms “might prematurely stop growth recovery and prove counterproductive,” says Michael Papaioannou, a visiting scholar at Drexel University and an expert in emerging-market debt.

Further illustrating the depth of the collapse, the International Monetary Fund, which has long drawn scorn for the austerity it demands of borrowers, has supplied Latin America and the Caribbean with more financing than any other region and is urging governments to spend. Most have.

In a region of serial defaulters, even the riskiest countries and companies have been able to borrow from capital markets as interest rates sit near record lows. Latin American governments borrowed a record of more than $65 billion on bond markets last year. Deficits more than doubled in four of the biggest economies, including Colombia’s, where it’s expected to continue to widen to 8.7% of gross domestic product this year, according to the IMF.

The worry, for investors and indebted governments alike, is that central bankers in the wealthy economies could reverse course and hike borrowing costs, which would hit developing nations the hardest. But paring back subsidies in the world’s most unequal region was politically explosive well before the pandemic. In 2019 violent protests forced the Ecuadorean government to reverse a fuel subsidy cut. In Chile, a proposed metro fare hike led hundreds of thousands to take to the streets to demand a new constitution.

Benjamin Gedan, deputy director of the Latin America program at the Wilson Center, a policy think tank, says Colombia’s unrest is going to make balancing budgets even harder. Leaders “are going to end up extremely gun-shy when it comes to any spending cuts or tax increase,” he says.

Already, governments are finding new ways to raise revenues and avoid cuts. Argentina levied a one-time wealth tax on its richest citizens. Brazilian President Jair Bolsonaro pushed through more than $23 billion in pandemic funding, largely to help the poor, despite facing automatic spending cuts and investor hand-wringing over Brazil’s fiscal situation. Chile has allowed its citizens to withdraw billions of dollars from their pensions as it faces pressure for more Covid-19 relief.

The problem for Colombia, a nation known for obsessing over its fiscal standing, isn’t that it spent an astronomical amount of money—its stimulus cost 4.1% of GDP in 2020, less than the regional average of 4.6%, according to the United Nations. It’s that it’s the only Latin American country on the cusp of losing investment-grade status, which it shares with Chile, Mexico, and Peru. Getting slapped with a junk rating has well-known consequences, not the least of which is increased financing costs.

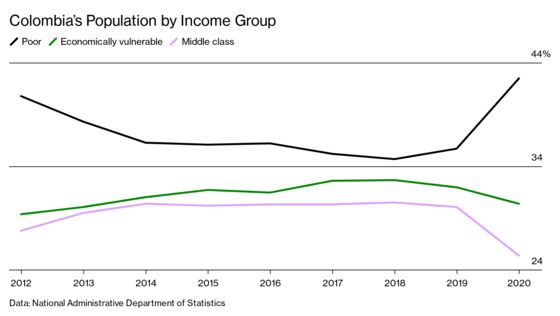

The rollout of the proposed reform baffled regular Colombians and political observers alike. “Anything with the words ‘tax reform,’ especially targeting the middle class, especially at this time, was going to be rejected,” says Silvana Amaya, senior analyst at Control Risks, a political risk-consulting firm in Bogotá. Over the past year, the share of Colombians living in poverty has swelled to almost 43%, while the middle class has shrunk.

The plan’s architect, Finance Minister Alberto Carrasquilla, who resigned on May 3, didn’t help matters. While defending a new value-added tax scheme that removed exemptions on some staples, he couldn’t say how much a carton of eggs cost. Almost all of Congress, even Duque’s own party, refused to back the bill.

And when the proposal was introduced, protesters were already mobilizing against Covid restrictions that have shuttered businesses and kept Colombians cooped up at home. A bloody police crackdown, which drew rebuke from human-rights groups and the U.S., brought thousands more Colombians onto the streets.

Duque pulled the tax bill less than three weeks after it was introduced. Carrasquilla resigned a day later. His replacement, José Manuel Restrepo, who was serving as the trade minister, has been assigned to come up with a new plan.

All of that did little to slow the protests. “What do we want? For me, it’s that Duque resigns,” said Daniel Rodríguez, a 19-year-old university student who draped a Colombian flag over his shoulder as he marched with hundreds down one of Bogotá’s main avenues on May 6.

Rising anti-government sentiment before next May’s presidential elections has been a boon for politician Gustavo Petro, a former guerrilla and ex-mayor of Bogotá. In 2018 he lost to Duque. But with Duque prohibited by term limits from running again, Petro, a leftist who has proposed major overhauls to the economy, is leading in the polls.

Andrés Abadia, an economist at Pantheon Macroeconomics, says Colombia ultimately needs reforms if it hopes to sustain growth. But getting them enacted requires demonstrating that they will be gradual and benefit those most in need.

“The government sinned in this sense,” he says. For other countries considering measures of their own, he adds, “clearly, now is not the moment.”

©2021 Bloomberg L.P.