Coin Shortages Are Causing a Liquidity Crisis at Laundromats

The coronavirus seems to have stopped up the flow of coins as people made fewer store trips and many businesses stayed closed.

(Bloomberg Businessweek) -- Every morning, Charles Boukas drives to six Chase banks in the San Diego area in search of quarters. The most he ever drove to was eight, but one branch was closed that day, and two others didn’t have change. Boukas, the 55-year-old owner of the Coin Hut Laundromat, is in a bind: He’s running low on quarters because residents of apartment complexes are making change and not using his machines. The whole trip takes about two hours, and the total amount of quarters he can get is worth $120 because his banks limit how many coins they give out. So he’s been seeking alternative sources.

Under couch cushions? Maybe not that far—but close. “Our biggest success has been friends and family so far, and the banks are just a daily grind that I do,” he says.

On top of a slowdown in foot traffic, laundromat owners such as Boukas are struggling because the coronavirus seems to have stopped up the flow of coins through the economy. People made fewer store trips and many businesses stayed closed with old change sitting in their tills. Even big retailers have felt the pinch, with many putting up signs at registers encouraging customers to use exact exchange or pay with plastic. Some have called it a national coin shortage, but as of April, the U.S. Treasury estimated that about $47.8 billion worth of coins were in circulation, compared with $47.4 billion last year.

“I don’t refer to it as a shortage, I refer to it as ‘We don’t have coin moving.’ It’s there, it’s just not in the right place,” says Jim Gaherity, chief executive officer of Coinstar, which collects loose change at machines that often are found in grocery stores. “It’s in homes. It’s probably in some businesses that haven’t reopened at this point in time. It’s in banks—so it’s there.”

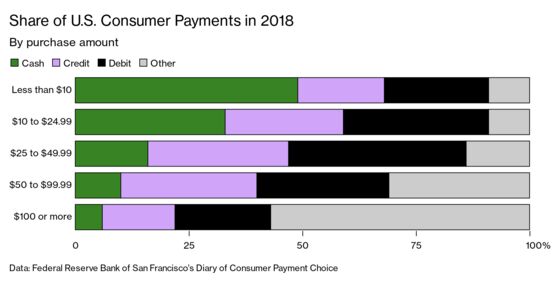

Even in an increasingly digital world, cash is used in 49% of payments below $10, according to a study from the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco. That’s led to a strange kind of liquidity problem. Since the lockdowns began, the U.S. Federal Reserve has gone to great lengths to ensure that big money keeps moving through the financial system. Need to sell millions of dollars of corporate bonds? The Fed stands ready to make it happen. Need 75 cents for the dryer? That could be trickier. “This is just an unexpected wrench in the works that I don’t think any of us could have anticipated, finding ourselves short on quarters,” says Brian Wallace, president and CEO of the Coin Laundry Association, which represents about 2,000 laundromats across the country.

Only a fraction of the laundromats in the association have what it calls alternative payment systems; about 20% have laundry card options and 27% accept credit cards, Wallace says. “The people that show up to the laundromat each weekend are there for a purpose,” he says. “It’s an essential service. Anything that impedes that progress certainly impacts tens of millions of families that use vended laundry each week.”

Coinstar plays a role in the recirculation of coins in America. Its green kiosks were responsible for processing $2.7 billion of coins last year. In the U.S., the company generally collects an 11.9% fee from customers, who take paper bills in exchange for their coins, though it also offers to pay in the form of gift cards with various retailers without the fee. A spokeswoman for the company says it saw coin volume decrease during the lockdown, but is seeing it return.

The company also operates in Japan, Canada, Italy, and several other European countries, but didn’t see this problem abroad. “There’s something unique about the U.S. that we can’t figure out why this has come to this crisis,” says Gaherity.

Once a kiosk is full of coins, Coinstar deposits them in a financial institution, which can recirculate the coins to customers such as Boukas. But he says a big chunk of the quarters he stocks in his change machines don’t make it into his washers and dryers. “I average $100 a day leaving the laundromat, going somewhere else,” he says. “I’m like a mini bank. They get change from me.”

Fed Chairman Jerome Powell said in June that he believed the shortage would be temporary. The U.S. Mint is increasing production, and the Federal Reserve formed a coin task force with industry stakeholders, including Coinstar, to come up with recommendations on how to fix the flow of coins.

Suggestions from the Coin Laundry Association and the National Automatic Merchandising Association, which represents the vending machine business, include the Fed distributing additional coins and prioritizing distribution to “consumer businesses in the essential critical infrastructure workforce.” Another obvious fix might be to pay people their now-precious loose change. For a week ending on July 21, Wisconsin-based Community State Bank ran a coin buyback with a $5 bonus for every $100 worth that customers turned in.

If he can’t find additional quarters, Boukas says his contingency plan is to take customers’ paper cash and operate the laundry machines manually. In the meantime, he’s been trying to dissuade the people who take his change elsewhere: “I explained to the apartment dwellers: ‘You come take coins out of here, you’re putting me out of business. You are asking me to go to the bank for you, in a way.’”

Read next: China Is Making Cryptocurrency to Challenge Bitcoin and the Dollar

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.