Builders of a $20 Billion Coffee Empire Have Their Eyes on Pets

Builders of a $20 Billion Coffee Empire Have Their Eyes on Pets

(Bloomberg Businessweek) -- Visitors walking into the Red Bank Veterinary Hospital in Tinton Falls, N.J., immediately know it’s not your typical trip to the vet. The building—one of the largest private animal hospitals in the U.S.—is a stately labyrinth of care rooms circling a lobby with a sprawling fish tank column at its center. There are auditoriums where practitioners present research on advances in veterinary science. Even the clientele of the facility, one of 42 practices operated by Compassion-First Pet Hospitals, are top-shelf: Bruce Springsteen’s dogs have been treated here.

“What I told everyone was that I wanted this group to become the Mayo Clinic of veterinary medicine,” says John Payne, who founded the company in 2014 after previously running veterinary hospital operations at Mars Inc. and Bayer AG’s animal health divisions. “It wasn’t just the quality of the medicine, which everyone says they practice, it was advancing specialty and emergency medicine that mirrored human care.”

Eager to expand his high-end care operation in the U.S. and globally, Payne knew he needed help from someone with deep pockets and an equally big appetite for growth. “I wanted,” he says, “people who bought into the vision.”

After talking to 33 potential investors, he found what he was looking for in an unlikely newcomer: JAB Holdings, the acquisitive Luxembourg-based investment company that likes to roll up businesses in highly fragmented industries in hopes of realizing efficiencies—and big investment gains—from their consolidation. JAB had spent the past seven years on a buying spree that turned it into the world’s second-largest maker of coffee, with brands from Peet’s and Douwe Egberts to Keurig, Green Mountain, and Stumptown. On May 29 it took its JDE Peet’s coffee operations public in an initial public offering that valued the company at more than €18 billion ($20 billion). Now JAB wants to apply the same playbook to the world of animal health care.

In February 2019 the company spent $1.2 billion to acquire Compassion-First. Four months later, it bought National Veterinary Associates, one of the largest companies in the industry, with more than 700 animal hospitals and rehabilitation resorts in Australia, Canada, New Zealand, and the U.S. JAB, armed with the virtually unlimited budget of sovereign wealth fund investors, endowments, and Germany’s billionaire Reimann family, is scouring the globe for more takeovers in what’s set to be the business world’s most ambitious effort to monetize the animal kingdom since the dawn of husbandry. “This is going to be a very big asset for us,” says Olivier Goudet, the 55-year-old French chief executive officer of JAB Investors. “We are in the first 10 years of an industry that will keep growing for the next 50 years.”

It’s easy to see why JAB would be attracted to veterinary investments. Just as many coffee drinkers can’t imagine starting each morning without their daily dose of caffeine, hundreds of millions more can’t imagine living without their pets. In the U.S., about two-thirds of the country’s households, or 85 million families, own a pet, according to the American Pet Products Association, compared with just more than half of households in the 1990s. Another way to look at current pet ownership: There are more than twice as many pet parents as there are parents with human children in nuclear households.

That’s fueling increased spending on ever-more sophisticated treatments to keep all those Rovers and Fluffys healthy. At Red Bank Veterinary, the annual profit from procedures such as removing pets’ brain tumors, open-heart surgery, repairing mitral-valve disease, and even operating on goldfish runs into the tens of millions of dollars.

Moreover, demand for veterinary care has historically been recession-proof. In the U.S., which accounts for about half of the global pet-care industry’s annual sales of $120 billion, the cost of veterinary treatment has risen by almost 40% over the past decade, according to the Nationwide Purdue Veterinary Price Index, with corporate-owned practices more aggressive on pricing than independent ones.

National Veterinary Associates’ revenue is growing through an even mix of price increases and the addition of more-expensive treatments that are helping extend pets’ life spans, according to Greg Hartmann, the company’s CEO. Over the past 11 years, National Veterinary’s pretax earnings have surged about fifteenfold, and Goudet says there’s plenty of growth to come.

This is a dramatic break from the past. Half a century ago, an American family’s dog usually slept outside and was fed whatever processed kibble was on sale at the supermarket. In recent years, however, a pet’s quality of life has increasingly been benchmarked against that of its owner, in some cases reaching extremes: D Pet Hotels, a chain of six locations in the U.S. headquartered in Hollywood, Calif., offers suites for dogs with flatscreen TVs at a rate of $200 per night, as well as a Rolls-Royce-chauffeured service. A pet’s diet has also been almost totally anthropomorphized by a proliferation of products from banana flaxseed vegan dog biscuits to Pawsecco nonalcoholic wine.

Meanwhile, the scope of veterinary services is becoming increasingly analogous to human medicine, with millennials and Generation Z owners driving much of the growth by spending vast sums on ambitious procedures. A dog’s double hip replacement can cost more than $10,000, while treating dogs for seizures can cost three times that amount.

Comprehensive oncology and dentistry treatments are also keeping animals alive longer. The life span of a dog today is almost twice what it was four decades ago. And when pets do die, many no longer end up buried in a shoe box in the backyard. Humane funeral services such as those offered by Dignity Pet Crematorium are increasingly common. The U.K. company incinerates departed pets and packages the ashes in a dazzling array of sarcophagi, including a bronze-effect casket molded in the shape of a guinea pig aimed at owners of a particularly beloved one. Cremating a chicken costs more than $100, which is cheaper than cremating a tortoise but more expensive than a lizard.

The $200 billion global business of domestic animals is expected to grow almost a third over the next five years. Pet food accounts for just under half of that, but that segment is almost entirely controlled by Mars’s Pedigree and Whiskas brands, Nestle’s Purina, and Colgate-Palmolive’s Hill’s Pet Nutrition, and JAB isn’t interested in competing against those entrenched players, Goudet says.

The investment firm’s focus will instead be on pet care, the largest segment of the pet industry—and health care is the fastest-growing parcel within it. The majority of hospitals and clinics in Australia, the U.K., and the U.S. are owned by independent veterinarians serving local communities. As with every buy-and-build strategy, absorbing large numbers of practices has benefits: reducing administrative overlaps, bulk discounts on orders of medicine, and information-sharing across a large veterinary network, which can shape other profitable pursuits such as drug development.

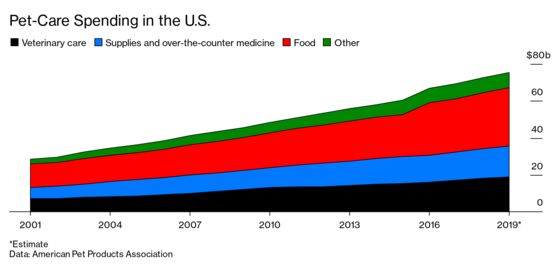

JAB’s venture into animal health could prove a decent hedge as its hospitality businesses, including Krispy Kreme doughnuts and Pret A Manger sandwich shops, bear the brunt of a global recession caused by the novel coronavirus. Historically, spending on pet care has kept rising through periods of contraction: In the U.S., it was up 29% during the dot-com bust of the early 2000s and 17% during the financial crisis later that decade, according to Mauldin Economics. Spending on veterinary services accounted for the lion’s share of those increases, climbing from about $5 billion to $35 billion over the past three decades.

JAB won’t be the only big corporate player in veterinary health. Mars, the maker of M&Ms and Snickers, is also the world’s largest owner of veterinary hospitals and clinics, managing thousands through its Banfield, BluePearl, Linnaeus Group, VCA, and Village Vet subsidiaries. Investors including Goldman Sachs Group Inc.’s merchant banking division and private equity giant KKR & Co. have also profitably flipped small veterinary outfits. But none has built a presence from scratch as big as JAB’s or as quickly. The combined revenue of Compassion-First and National Veterinary Associates will be $3 billion this year, placing it among the three largest players in the industry barely 12 months after the firm’s first takeover.

For a road map of what JAB is seeking to accomplish in veterinary services, investors need only look at its history in coffee. Less than a year after Goudet joined the investment firm in 2012, he led its acquisition of Peet’s Coffee & Tea Inc. for about $1 billion, then spent several billion dollars more over seven years acquiring the coffee brands owned by Oreo maker Mondelēz International, such as Jacobs and Carte Noire. He then merged them with D.E. Master Blenders 1753, the Dutch giant behind Douwe Egberts and L’Or coffees. He also picked up a dozen high-end roasters including Chicago’s Intelligentsia and Portland’s Stumptown.

The strategy was straightforward: Assemble dozens of competing businesses to create a company singularly focused on coffee, and then take it public. So if an investor wants to invest in Big Coffee but not also Nestlé’s sugar business or Starbucks Inc.’s real estate, JDE Peet’s would be the only game in town, Goudet figured. That tight focus seems to have worked with investors, who on May 29 sent JDE Peet’s shares up almost 16% on their first day of trading. It was Europe’s largest IPO in more than a year, leaving the combined coffee businesses valued at nearly double what they’d been worth apart.

JAB’s frenetic dealmaking has drawn criticism that it’s overspent to acquire businesses, left some operations with precarious levels of debt, and allowed underperformance at some of the companies it owns. Last year, Bart Becht, a JAB partner who formerly served as CEO of consumer-products giant Reckitt Benckiser Group Plc, stepped down from the investment company after failing to persuade his colleagues to kick their buyout habit and spend more time improving operations at the businesses they’d purchased. Goudet says the cause was a difference of opinion about JAB’s focus, which he feels should be judicious investing rather than in-the-weeds management of the businesses it owns.

That suggests JAB will keep on buying targets that advance its strategy even when others may think the price is too dear—as happened in 2015 when it agreed to buy coffee roaster and brewing systems company Keurig Green Mountain for $13.9 billion—a 78% premium.

“I literally had so many calls saying, ‘Are you out of your effing mind, 78% price premium?’ but one year later, we had doubled our equity value,” Goudet says with a shrug. The deal ultimately paid off, as he’s hoping it will in pet care, where JAB is already outspending bidders to get the businesses it wants. “I’ve heard that we always overpay,” says Goudet, “but I’m telling you, the question is not the price you pay—it’s the value you get.”

Read next: Private Equity Is Ruining Health Care, Covid Is Making It Worse

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.