How Food Samaritans Help Supermarkets Reduce Waste

How Food Samaritans Help Supermarkets Reduce Waste

(Bloomberg Businessweek) -- By day, Laura Gaga works as a civil servant in London. Her evenings and weekends, though, are dedicated to reducing food waste. On a typical Sunday afternoon, Gaga, 41, checks an app called Olio to find out whether her local Tesco Plc supermarket or Pret A Manger Ltd. sandwich shop have listed items for free collection. Then she zips over to round up loaves of bread, produce, and wraps not expected to sell before their “use by” date. Back home, she uploads details of her bundle to the app for neighbors to claim.

Gaga, who also blogs and produces a podcast about food sustainability, is one of 30,000 volunteers in 59 countries who use Olio. “Living in London, you don’t have to walk very far to find someone who is hungry or homeless,” Gaga says. Food waste “is unnecessary and something that we can all do something about.”

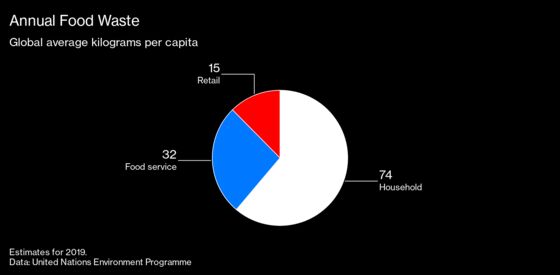

Waste from the food industry accounts for as much as 10% of global greenhouse gas emissions, according to the United Nations Environment Program, including gases from food production and the methane released when it breaks down in landfills. The UNEP says 14% of food is lost from harvest to retail—$400 billion worth of items that consumers never see—and 17% of total food production makes it to market only to be thrown out by retailers, food service providers, or consumers.

To build awareness of the problem, food-waste apps are sprouting up, offering consumers an opportunity to help fix it. “We are only just starting to scratch the surface when it comes to this issue,” says Mette Lykke, the chief executive officer of Too Good To Go, a Copenhagen-based app that lets consumers in 15 European countries pick up discounted pastries and other items left at the end of the day from bakeries and cafes.

Too Good To Go, which has 46 million users, takes a cut of the price consumers pay for the food it diverts, and says it has saved 96 million meals from being tossed. Olio says it’s funded by fees supermarkets and shops would pay disposal companies to haul the food away. The company says it’s saved 32 million servings—almost 3 million pounds in 2020—mainly in the U.K.

French supermarkets are forbidden from destroying unsold food and are ordered to donate it instead. But in many countries, the donation of excess food to charitable organizations by food business operators is limited because of legal and other hurdles, including tax barriers, liability, and date-marking issues.

In the U.K., the nonprofit FareShare, which annually redistributes 5.2 metric tons of surplus food to charities, says subsidies for anaerobic digestion plants make it cheaper for farmers to toss food into a biogas digester than get it to hungry people. Even when grocery stores or farmers are prepared to divert surplus to charities, it’s a logistical challenge to get it to the right place—often soup kitchens or homeless shelters—in time for consumption.

That’s where apps can come in. Kitche, a fledgling app with 25,000 users in the U.K., is going after households, the source of 61% of food waste, according to the UN. Kitche lets users keep track of what’s in the fridge by scanning supermarket receipts and reminding them when food is about to go bad. The company says regular users save 8.2 kilograms (18 lbs.) from being tossed unnecessarily each year.

While consumers can play a role in curbing waste, big food companies can have the greatest impact, says Rob Opsomer of the Ellen MacArthur Foundation, which campaigns to make the economy more sustainable. One option, championed by a group called the Upcycled Food Association, is to use surplus ingredients to make longer-lasting products such as veggie chips, snack bars, or baking mixes. Nestlé SA, for instance, has piloted Krumm Glücklich (“Crooked but Happy”), a line of soups made from vegetables that would otherwise have been thrown away. “We need to move upstream,” says Opsomer, “and look at the major companies that put the products on the market in the first place and move millions of tons of materials.”

Read next: Climate Change to Cut Quarter Off Corn Yields by 2030, NASA Says

©2021 Bloomberg L.P.