Who Wants to Lead America’s Poorest Big City Out of a Pandemic?

Who Wants to Lead America’s Poorest Big City Out of a Pandemic?

(Bloomberg Businessweek) -- When Monique Jones moved from Atlanta to Cleveland last year to care for a sick family member, she was shocked by the poor condition of the roads and that she couldn’t get high-speed internet at home. “It’s like they’re back in the past here,” says Jones, 47. “Atlanta is just so far ahead. This city has a lot to deal with.”

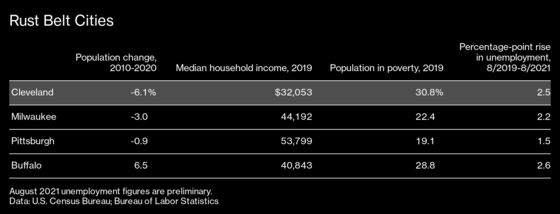

By U.S. Census Bureau figures, Cleveland is the poorest big city in the U.S., with 30% of residents and 46% of children living below the poverty line. Its digital divide is one of the country’s worst, with 30% of residents lacking reliable high-speed internet. The city has lost 6% of its residents since 2010, and its current population of 372,624 is the lowest since the 1800s. The post-recession recovery that’s lifted other Rust Belt and midsize cities seems to have bypassed Cleveland altogether, even as several wealthy suburbs surrounding it in Cuyahoga County have thrived.

That’s the troubled backdrop for the race to elect Cleveland’s first new mayor in 16 years. The Nov. 2 election pits longtime City Council President Kevin Kelley, 53, against a political newcomer, 34-year-old Justin Bibb, a business and nonprofit executive who’s positioned himself as a millennial outsider. (Although the election is officially nonpartisan, both Kelley and Bibb are Democrats.)

Whichever candidate replaces four-term Mayor Frank Jackson faces economic turmoil and deeply entrenched inequality as the city moves out of the pandemic. But he also has a unique resource. The federal American Rescue Plan sent $511 million to Cleveland—money that could jump-start a new chapter in the city’s history. Richey Piiparinen, director of the Center for Population Dynamics at Cleveland State University, says the next mayor has a “great opportunity” to use that money to train workers and correct the city’s health disparities.

Bibb placed first in a seven-person primary in September with 27% of the vote, drawing a coalition of minority and young voters to defeat better-known candidates including former mayor and U.S. Representative Dennis Kucinich. Born and raised in Cleveland, Bibb studied urban policy and politics at American University and interned in Barack Obama’s Senate office in 2007. After working in development in several other cities, he returned to Cleveland in 2014 and has worked in finance at KeyBank and as chief strategy officer at the nonprofit Urbanova.

“I think in this post-Obama, post-Trump world of electoral politics, we’re seeing not only a hunger for change but a hunger for urgent change,” Bibb told Bloomberg Businessweek right after speaking at a rally against gun violence. (A recent homicide spike is another issue that’s bedeviled the city of late.) “Voters want leaders that are going to fight, bring results, be relatable and honest and transparent. The whole notion of running for office has been disrupted.”

Bibb wants Cleveland to follow the lead of cities such as Pittsburgh and Louisville, which moved beyond their industrial pasts and transitioned to more tech-based economies after the 2008 recession. He wants to modernize city hall with a new website and more responsive staff. He would use the federal relief funds to create an economic recovery office to help close the digital divide and clean up lead pollution. He also proposes to revitalize neighborhoods from the ground up, “hyperlocalizing” new development and initiatives based on community feedback, rather than having city hall impose one-size-fits-all solutions.

Several Rust Belt mayoral races this fall are pitting progressive outsiders such as Bibb against more establishment candidates. Farther up Lake Erie, socialist India Walton topped incumbent Byron Brown in Buffalo’s mayoral primary and will face him again—with Brown a write-in candidate—in November. In Cincinnati voters will choose between 81-year-old former Mayor David Mann and 39-year-old Aftab Pureval, Hamilton County’s clerk of courts. And Pennsylvania state Representative Ed Gainey is poised to replace incumbent William Peduto and become Pittsburgh’s first Black mayor.

In Kelley, Bibb faces an opponent who represents establishment politics—albeit with a progressive agenda of his own. Following a career in social work and the law, Kelley has served on the city council since 2005, the last eight years as its president. Kelley says he has a unique blend of experience and liberalism. From his city hall office window overlooking Lake Erie, he can often see a line of cars outside a food bank—evidence, he says, of the unequal recovery that dogs the city.

“Right now the city of Cleveland is in a very fragile place,” Kelley says. “We need somebody who has experience not just with government but with follow-through and accomplishments you can point to.”

He’s proposed using the rescue plan money on a New Deal-style jobs program: training and hiring local workers to remove and refurbish vacant homes, remove lead contamination, create public art, and install solar panels.

Kelley points to the broadband network he installed in his Old Brooklyn neighborhood and investments in local parks as proof that he can do the work Clevelanders need. “Change is an easy message for people to grasp,” he says. “My message is that anyone can say ‘change,’ but change in government is hard.”

Kelley has been endorsed by the Cleveland Building & Construction Trades Council and other unions, three sitting council members, and outgoing Mayor Jackson. He reported more than $500,000 cash on hand in August (the last reporting deadline), compared with Bibb’s less than $400,000.

Bibb touts support from local and national Democratic groups, including the Bernie Sanders-affiliated Our Revolution Ohio, Senator Sherrod Brown, and a pair of former Cleveland mayors, Michael White and Jane Campbell. The Cleveland Plain Dealer also endorsed Bibb.

CSU’s Piiparinen says both candidates have proposed bold agendas and could improve the city “if they grapple with the issues facing citizens” and realize that “economic progress can’t mean social regress.” He sees momentum for progressivism in Cleveland because of its college-educated millennials: A 2016 study by his center at CSU found that the city was eighth in the nation for attracting them.

The choice Cleveland will make reflects some broader political forces, says Richard Schragger, author of City Power: Urban Governance in a Global Age and a professor at the University of Virginia School of Law. Cities typically see a “cycling between machine and reform politics,” but local races are increasingly reflecting the national leftward shift of the Democratic Party in the past two years, he says: “The way the federal government has come in very big with pure cash support, that has in some ways reflected a wider acceptability of the arguments of the progressive left at all levels.”

Read next: Atlanta’s Wealthiest and Whitest District Wants to Secede

©2021 Bloomberg L.P.