Lagarde’s Mixed Report Card After One Year at European Central Bank

Lagarde’s Mixed Report Card After One Year at European Central Bank

(Bloomberg Businessweek) -- When Christine Lagarde became president of the European Central Bank on Nov. 1 last year, she had two tasks she wanted to accomplish. The first was to reconcile the ECB’s fractious governing council after its eight divisive years under her predecessor, Mario Draghi. Second, she wanted to build bridges with the wider public by improving how the central bank communicated its policies and perspectives.

As her first anniversary approaches, only one of these goals has been fulfilled—and it is not clear how long it will last. The governing council has stood largely united as the ECB took a number of unprecedented steps to stimulate the euro zone’s economy and bolster financial stability through the pandemic. However, longstanding divisions are already reemerging ahead of the central bank’s December meeting, when it may discuss taking additional measures.

Despite declaring it a goal at the beginning of her tenure, Lagarde’s challenge has been getting her message out. She said that her press conferences would be different from those of the technocratic Draghi; she has indeed given significantly more interviews than the media-shy Italian. And unlike Draghi, she has kept a Twitter profile, using it to push her favorite campaigns, for example the promotion of women to senior leadership roles.

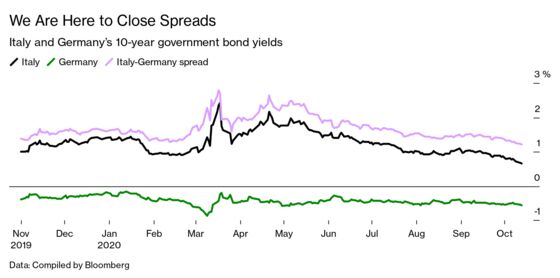

But the most memorable moment of her first year in office was a slip in March, in what was just her third press conference, as she was announcing a sizable stimulus to counter the pandemic shock. Asked about sovereign spreads in the euro zone—a particularly sensitive issue for Italy, which was seeing its bond yields climb relative to Germany’s—Lagarde said: “We are not here to close spreads. This is not the function or the mission of the ECB.” Investors took it as a sign that the ECB was no longer willing to stand behind euro zone member states in periods of financial stress. Italy’s bond yields climbed sharply, forcing Lagarde into a contrite U-turn.

The ECB president is a lawyer by training and has relatively little formal education in economics. However, she has been both finance minister of France and managing director of the IMF. Since the bond spread faux pas, she has regained some composure, but there are lingering questions over her feel for the market reaction to monetary policy decisions. She now often reads from scripted texts at press conferences.

The pandemic has posed a formidable challenge in Lagarde’s first year in office. As Covid-19 started to appear across Europe, the ECB was slow off the blocks. Lagarde was the last among major central bankers to acknowledge the risks from the pandemic; her chief economist, Philip Lane, initially said he expected a “V-shaped” recovery—one in which a quick rebound follows a steep recession. The ECB has progressively changed tack: It now expects the economy to rebound only gradually, and inflation to stay lower than its target of “below but close to 2%” as late as 2022.

The good news is that the central bank eventually did what was needed to counter the economic shock. It provided generous liquidity to the banking system, ensuring it could keep lending to companies and businesses. It temporarily relaxed its prudential rules, so banks had to worry less about their levels of regulatory capital. In successive steps, it unveiled a sizable asset-purchase scheme, worth €1.35 trillion ($1.59 trillion), and moderated its rules to accept as collateral bonds both from weaker sovereigns such as Greece and from troubled companies that had lost their investment rating as a result of the pandemic. Most important, it set aside its self-imposed restriction on purchasing government paper in line with the relative size of their economies. That way, the ECB could concentrate its firepower on Italy’s sovereign bonds, buying more of them than it would according to its old rules and helping to calm the financial markets.

Lagarde deserves credit for ensuring that the ECB stood broadly united behind these measures. Monetary policymakers in the euro zone traditionally split along national lines. Those from countries such as Germany and the Netherlands tend to resist interest rate cuts and especially, asset purchases. These divisions simmered through Draghi’s term in office, with Jens Weidmann, president of Germany’s Bundesbank, going as far as testifying in court against the ECB, alleging that the “outright monetary transactions” program unveiled at the height of the euro zone crisis undermined the credibility of monetary policy. The rancor erupted toward the end of 2019; Sabine Lautenschlaeger, the ECB’s executive board member from Germany, resigned after the board decided to restart a program of quantitative easing. Draghi’s personality probably did not help: For all his brilliance as an economist and a communicator (most memorably for his “whatever it takes” remarks that rescued the euro zone in 2012), he was criticized for front-running the governing council and showing little interest in other people’s views.

The new president sought to mend those bridges. She immediately summoned an out-of-office meeting of the governing council to allow for all members to have their voices heard. In return, she obtained a more gentle opposition. The Dutch and German central banks did disagree with her pledge in March to have “no limits” in her efforts to shore up the euro zone. However, Klaas Knot, the governor of the central bank of the Netherlands, has sounded much less critical of the ECB’s policymaking than he was under Draghi. Even Weidmann, who remains skeptical of policies such as asset purchases, has been less abrasive in his resistance.

The hard-won consensus is fragile. The resurgence of the pandemic in Europe has strengthened the voices of those arguing for additional stimulus to keep the euro zone economy afloat. However, once the medical emergency abates—perhaps with the development of a working vaccine—views are bound to diverge over how fast to withdraw the extraordinary rescue measures taken this year. Lagarde’s diplomatic skills will then be seriously put to the test.

The ECB will also face a lively debate over its long-term future. She’s had to delay a review of the ECB’s monetary policy strategy—the first in nearly 20 years—a long-term project that was to take up the better part of 2020. As the process gathers speed, it will inevitably splinter the central bank on several issues.

First, the new president has signaled that the ECB may mimic what the U.S. Federal Reserve has embraced in the strategic overhaul it announced at the end of August: pledging to avoid tightening monetary policy if inflation rises above its target as a way to compensate for past periods of low inflation. This approach has already prompted a skeptical rebuttal from the Bundesbank, which does not want to undermine the ECB’s reputation as an inflation-buster.

Second, policy makers are likely to be divided over the question of the future of asset purchases. The pandemic has prompted the ECB to relax those self-imposed constraints on quantitative easing. However, the central bank has made it clear that this exception is strictly tied to the pandemic period, since deviating from it in normal times could violate a decision from the European Court of Justice. Still, some within the central bank believe the additional flexibility would serve the ECB well, even in normal times—which will lead to lengthy and complicated discussions.

Finally, Lagarde has stated she wants the ECB to “explore every avenue” in the fight against climate change. This aspiration, which could prompt the central bank to skew its asset purchases in favor of green assets, has already met with skepticism from the Bundesbank. Weidmann said in a speech that he fears this additional objective could prompt accusations of central bank overreach and, in turn, undermine its independence. Lagarde has been passionate about climate change, so a failure to achieve meaningful reform in the central bank’s actions and objectives could prove embarrassing.

Part of any central bank chief’s job is to inspire confidence. Lagarde’s mistakes have reopened old questions about her technical competence. The president has found a very useful ally in ECB chief economist Lane. He has complemented her public comments with regular blog posts that have often helped to clarify the central bank’s thinking on the course of monetary policy. However, in recent months, Lane and Lagarde appear to have given slightly different messages—for example over the resilience of the euro zone economy as it faces a second wave of the pandemic. In September, the chief economist sounded more alarmed about the impact of a strengthening euro than the president did just a day earlier. These discrepancies are more in tone than substance—but they risk muddling the central bank’s message at a crucial juncture.

The president is only in the first year of an eight-year term. The pandemic has made her face a blistering start, dealing with developments that were in many ways outside the ECB’s control. The paradox is that Lagarde could find that her job becomes more difficult when the pandemic eventually recedes, allowing the divisions in the governing council to resurface. The new president will then need to assert her authority, much as her predecessor had to do. A strong dose of credibility with the financial markets and the general public are the best tools to deal with internal conflicts. As Lagarde prepares for her second year in office, she will want to build just that.

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.