China Tries to Cool Down an Easy-Money Financial Trade

China Tries to Cool Down an Easy-Money Financial Trade

(Bloomberg Businessweek) -- With the global economy reeling from the novel coronavirus crisis, Chinese policymakers want to encourage lending so companies can stay alive and grow. The People’s Bank of China injected a net 1.4 trillion yuan ($198 billion) into the financial system during the first quarter of 2020. But recently it’s ratcheted some of those efforts back with moves that helped send corporations’ costs of funding to a five-month high.

Why would the central bank do that? It may be trying to control the growth of a hot financial product known as structured deposits.

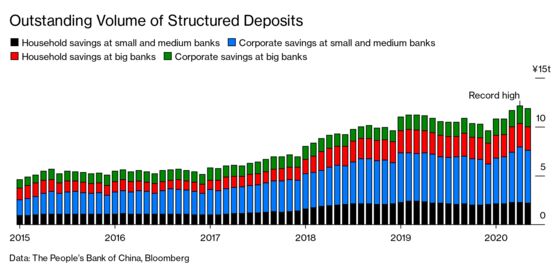

Structured deposits are like bank savings accounts, but with a little something extra on top. They pay a fixed yield but also offer the potential for additional gains depending on the performance of, say, gold prices or a stock index. Many Chinese companies are using structured deposits to make an arbitrage play: First they borrow money at a relatively low rate, and then they park it in a higher-yielding structured deposit, pocketing the difference. A record 12.14 trillion yuan was invested in structured deposits as of April, before Beijing imposed caps on them.

The arbitrage practice is so widespread that some on Wall Street say it’s helped create the illusion of a rapid recovery in credit growth in China—companies may be borrowing, but they’re not necessarily using the money to invest in their real businesses. Instead, some of it’s going into souped-up financial instruments. This may frustrate some of the PBOC’s stimulus efforts, potentially undermining a recovery in the world’s second-largest economy.

Financial arbitrage is common in China because of its complex system of regulated interest rates, a legacy of the country’s command economy. That, combined with an uncertain economic environment that made companies reluctant to invest, created the perfect conditions for the rise of structured deposits. The products are sold mainly by small and midsize banks, some of which have struggled to find enough funding to play their part in China’s lending push.

But Chinese banks, especially the smaller, cash-hungry ones, may end up being the biggest losers of the structured-deposits boom. Banks are offering generous yields they may not be able to fund for much longer, especially if a prolonged period of low interest rates on the loans they make squeezes their profitability. The practice also has risks for companies because it encourages them to borrow more.

“I expect regulatory vigilance on financial arbitrage risks and window guidance, and potentially tighter regulation,” says Linan Liu, Greater China macro strategist at Deutsche Bank AG. Window guidance is policymakers’ practice of giving banks informal instructions and signals about what to do.

When Premier Li Keqiang delivered the government’s annual work report in May, he said officials should tighten rules to “prevent funds from simply circulating in the financial sector for the sake of arbitrage.” One bank was recently fined 500,000 yuan for violating regulations on its structured deposits business.

Policymakers seem to be trying to take some of the fuel out of the market in part by pulling back some of their lending stimulus. The PBOC shocked investors in the second quarter by allowing some of the loans it holds to mature without replacing them, effectively withdrawing medium-term funding from the financial system. It also confused analysts in June by not touching the amount of cash that banks are required to set aside in reserve—even though China’s cabinet signaled a reduction was looming.

This doesn’t mean the PBOC is planning to tighten altogether. It’s still expected to cut the reserve-requirement ratio within the next three months. It also said last month it would start purchasing loans made to small businesses from some local banks, a new policy to help boost the supply of lending in the real economy.

China recently told lenders to stop issuing structured deposits with yields incompatible with their risks, according to local media. In June authorities asked some midsize banks to cut their balance of the products to two-thirds of last year’s levels by the end of 2020.

Those measures helped reduce the outstanding volume of structured deposits by 2.8%, to 11.8 trillion yuan, in May. Still, some analysts predict the practice will reemerge as soon as the PBOC loosens policy again. Even if the money doesn’t land in structured deposits, it may flow into new kinds of contracts created by China’s financial industry, which could be harder to spot. “Arbitrage can become more secretive compared with the current, more straightforward practice of buying structured deposits,” says Shujin Chen, a China banking analyst with Jefferies Group LLC. —With assistance from Xize Kang and Shuqin Ding.

Read next: Coronavirus Couldn’t Pop China’s Economic Bubble. What Will?

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.