Mao’s ‘Magic Weapon’ Casts a Dark Spell on Hong Kong

Mao’s ‘Magic Weapon’ Casts a Dark Spell on Hong Kong

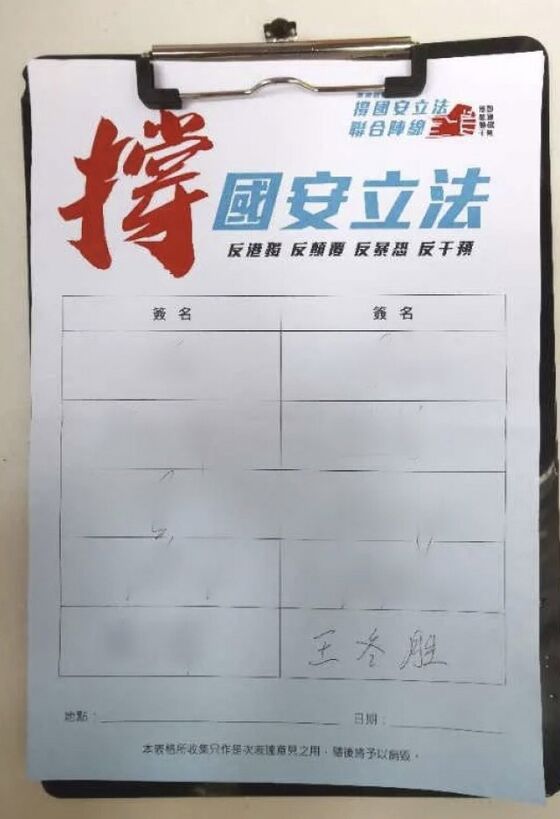

(Bloomberg Businessweek) -- The photograph shows Peter Wong, HSBC Holdings Plc’s top executive in Asia, stooped over a folding table outside a Hong Kong subway station signing a petition in support of China’s plan to impose national security legislation on the city. When the bank posted the picture on social media on June 3, it sent a chill through the business community.

Days earlier, a former Hong Kong chief executive and a vice chairman of the Chinese government’s political advisory body had castigated the bank for not issuing a statement backing the legislation, as other companies, tycoons, university heads, and countries had done. It happened just as a campaign orchestrated by the Chinese Communist Party—with the help of an organization called the United Front Work Department—was starting to drum up support for a move that the U.S., the U.K., and other Western nations have said violates the “one country, two systems” autonomy of Hong Kong that China promised through 2047.

The announcement that Beijing would impose the legislation after a year of protests against its intervention in Hong Kong’s affairs has raised concerns that the move could jeopardize the city’s economy and its role as a global financial center. It has heightened tensions with the Trump administration, which threatened sanctions against Chinese officials and possible bans of U.S. high-tech exports to Hong Kong, pending the final wording of the new laws and details about how they would be enforced. The U.K. also condemned the move and is considering offering the right of abode to as many as 3 million Hong Kong residents.

The pressure campaign coincides with increasingly assertive messaging by China as it seeks to bolster its stature abroad. Its diplomats have taken to social media to spread China’s worldview, and their posts are amplified by an army of trolls. Twitter on June 12 removed more than 170,000 accounts involved in a China-linked organized information campaign.

The bullying of HSBC in Hong Kong stood out because of its stature as a global corporation based overseas. Other big companies and individuals offering support for the legislation—Jardine Matheson Holdings Ltd., Swire Pacific Ltd., Hong Kong’s richest man, Li Ka-shing—are locally based. HSBC’s headquarters are in London, but it derives more than 40% of its revenue from Hong Kong and China. It’s also one of three banks issuing Hong Kong’s currency, along with Standard Chartered Plc, which quickly followed with its own statement of support. The pressure sent a signal that from now on, if it wasn’t clear already, things will be different for companies wanting to maintain business as usual in Hong Kong.

“It’s really causing a chill,” says Mark Clifford, executive director of the Asia Business Council, a group of corporate leaders from around the region. “The demand for political correctness has never been as prominent as it is today, and it’s likely to change the feel of Hong Kong as a free and open business center.”

The United Front’s mission is to increase the Chinese Communist Party’s influence. Created in the 1920s, it was hailed by Mao Zedong as a “magic weapon” in the victory of the communist revolution. President Xi Jinping repeated those words in 2015 when he set about revitalizing it. Since then, Xi has nearly doubled the organization’s size, according to Alex Joske, an analyst at the Australian Strategic Policy Institute who published a report about the United Front on June 9. Its work, he writes, includes espionage, influence campaigns, and engagement overseas in service of the party’s aims.

The United Front’s handiwork in Hong Kong, normally conducted behind the scenes, became apparent after last month’s meetings of the National People’s Congress, China’s legislature, as well as its top political advisory body, the Chinese People’s Political Consultative Conference, known as the CPPCC. Chinese officials there announced that national security laws to outlaw secession, sedition, and acts of treason were being drafted in Beijing to be enacted in Hong Kong.

The CPPCC is the premier United Front forum for drawing together Communist Party officials and elites, says Joske, who has written extensively about the party’s influence. After former Hong Kong Chief Executive Leung Chun-ying returned to the city in late May, he sought to rally support for the laws. Leung, a vice chairman of the National Committee of the CPPCC, attacked HSBC in a Facebook post for not quickly endorsing the legislation. “On political matters, this self-proclaimed British bank can’t make money from China while following other Western countries trying to damage China’s sovereignty, dignity, and people’s feelings,” Leung wrote. HSBC’s business could be replaced overnight by Chinese banks, he said, and suggested that Chinese and Hong Kong officials let “HSBC know which side their bread is buttered.”

A spokesman for Leung says he hasn’t participated in the United Front campaign and was “surprised” by any suggestion otherwise. HSBC’s Wong, who’s also a member of the CPPCC, declined to comment, as did a spokeswoman for the bank. HSBC previously said it supports laws that “will enable Hong Kong to recover and rebuild the economy and, at the same time, maintain the principle of ‘one country, two systems.’” The United Front office in Beijing didn’t respond to a faxed request for comment on the organization’s involvement in efforts to boost support for new laws.

The United Front’s work in Hong Kong is carried out under the umbrella of the State Council’s Liaison Office, which oversees China’s affairs in the special administrative region. China’s official news agency Xinhua published a photo in early June of the head of the office, Luo Huining, receiving boxes of petitions supporting the national security laws with what it said were 2.9 million signatures gathered online and at public booths like the one where Wong signed. That’s about 40% of Hong Kong’s population, far more than the number of voters backing the pro-Beijing candidates trounced in last year’s district council elections.

The man giving him the petitions is Hong Kong politician Tam Yiu-chung, identified as an organizer of a group called the United Front Supporting National Security Legislation. Tam, a member of the decision-making Standing Committee of China’s National People’s Congress, has called for barring candidates for Hong Kong’s Legislative Council from running in September if they don’t support the laws or have spoken out against them—a move that would disqualify almost every opposition politician.

Opinion pieces by Hong Kong government officials, newspaper ads, and a flood of public service announcements have sought to reassure residents that the legislation will be good for stability. In a June 5 webinar with the Hong Kong General Chamber of Commerce, several business leaders who were delegates at the Beijing meetings repeated that messaging, saying the proposed laws would make doing business safer by putting an end to the demonstrations that paralyzed Hong Kong last year and that their imposition won’t affect Hong Kong’s autonomy. A spokeswoman for the Hong Kong government said in an email that the new national security legislation “will ensure Hong Kong’s long-term stability and prosperity” and add to the city’s economic competitiveness. “We appeal for the community’s full understanding and staunch support for the legislation,” she said.

The Hong Kong Chamber of Commerce session followed a survey in which 80% of its members said they were concerned or very concerned about the national security legislation. An American Chamber of Commerce survey in early June found 83% of its members expressed similar views. “It will damage the overall business environment of HK that is used to being free, with fair legal, financial, and juridical systems,” one respondent wrote.

The Communist Party stepped up its United Front activities in Hong Kong in the 1980s, after the U.K. and China signed an agreement that the city would be handed over to Chinese control in 1997, according to Underground Front: The Chinese Communist Party in Hong Kong, a book by Christine Loh, a former government undersecretary during the Leung administration. After 1997, the front embarked on a campaign to co-opt Hong Kong’s capitalists. “The purpose of the strategy was to influence the outlook and decisions of the leaders in various fields in Hong Kong because the party regarded them as important shapers and influential agents of its governing values and beliefs,” Loh wrote. “Moreover, the United Front enabled the targeted groups to grow accustomed to the fruits of their membership in the post-reunification establishment so that they have a stake in maintaining it.” Those who didn’t support United Front activities became the focus of attack for being “unpatriotic,” according to Loh.

The result is a United Front-affiliated network around the Liaison Office: associations, business groups, state-owned and mainland-based companies, pro-China politicians, academics, and media. “The Liaison Office can call on this network to support party policy in Hong Kong,” says John Burns, emeritus professor and former chair of politics and public administration at the University of Hong Kong. Many of those involved “can anticipate what the party needs and what the central government needs” without written directives, he says. “As soon as it became known that the central government is pushing forward with the national security laws, I’m sure they’re thinking, ‘How can we support this?’” The Liaison Office in Hong Kong declined to comment by phone and asked that questions be sent by mail.

Diplomats in China’s overseas embassies, managers in state-owned enterprises, and the heads of organizations with words like “friendship” and “unification” in their names also carry out United Front work, according to several reports about the group’s structure, including the one by Joske, the Australian analyst. Countries including Zimbabwe, Syria, Serbia, North Korea, and Pakistan have issued statements backing the legislation, along with five China-Sri Lanka “friendship” organizations. Cuba, Iran, and Russia also offered support for China to ensure security in Hong Kong.

Demands for declarations of loyalty, known as biao tai, are a long-standing practice of the Communist Party, notes David Zweig, director of the Center on China’s Transnational Relations at the Hong Kong University of Science and Technology. “That kind of display is very Chinese,” he says. U.S. Secretary of State Mike Pompeo used the term “kowtow” in a statement criticizing China for requiring HSBC to support the laws, referring to the ancient practice of prostrating oneself in front of the emperor. The word became well-known in the West after China’s emperor in 1793 requested that British envoy George Macartney bow his head to the floor to secure access to China’s ports for British traders.

Hong Kong’s business community has become increasingly familiar with what happens when they don’t show support for government positions. Last year, Hong Kong Chief Executive Carrie Lam tried to push through an extradition bill that would allow Hong Kong residents to be taken to the mainland for trial, sparking the demonstrations. Some business groups expressed concerns about the law.

What happened to Swire Pacific, the parent company of Cathay Pacific Airways Ltd., serves as a lesson. When some airline employees indicated support for the pro-democracy movement on social media and a pilot uttered a slogan used by protesters as he landed in Hong Kong, Cathay’s senior executives didn’t immediately condemn them. But China’s airline regulator stepped up inspections and refused to allow employees who’d supported the protests to fly to China, the airline’s most important market, or even over its airspace.

Cathay then fired a number of employees. But that didn’t save Chief Executive Officer Rupert Hogg and one of his deputies, who also lost their jobs. So did Chairman John Slosar, who in the midst of the controversy had said that he “wouldn’t dream” of telling employees what to think. A proposal by the airline to save itself from potential bankruptcy by consolidating with its budget carriers, Cathay Dragon and Hong Kong Express, was denied by China’s regulators earlier this year. The denial was viewed in Hong Kong as continued punishment by Beijing, says Carol Ng, chairperson of the Hong Kong Confederation of Trade Unions, a pro-democracy labor group that represents employees in aviation, transportation, and other industries.

Swire was among the first of the large Hong Kong companies to announce support for the new laws. On June 9, Cathay received a $5 billion government bailout, saving it from collapse. “You cannot stay neutral,” says Ng. “In the eyes of the Chinese Communist Party, if you don’t make these comments, it means you are not supporting them, and they will mark your name and come back on you later.” Yet what worries many in the business community, Ng says, is that one-time declarations will never be enough and that their freedom to operate will be curtailed. “You can never fill the CCP’s stomach,” she says. “There are other companies in China waiting to replace you. The more you back down, the more you will lose.”

HSBC, which was founded in Hong Kong and Shanghai in 1865, may soon find that out. An article in the mainland Global Times, which often indicates the thinking of China’s senior leadership, declared that HSBC “finally” backed the national security legislation, but quoted Song Guoyou at Fudan University in Shanghai as saying that the bank would need to follow up with concrete actions to show sincerity: “It would be the bank’s actions in the days to come that matter.” —With Iain Marlow

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.