China’s Tab at World Bank May Get Squeezed Under Trump’s Nominee

China’s Tab at World Bank May Get Squeezed Under Trump’s Nominee

(Bloomberg Businessweek) -- In the summer of 1981, a poor, technologically backward country looking to move up in the world got its first loan from the World Bank. China borrowed $200 million to modernize its universities so they could churn out more scientists and engineers—a big step for a nation whose average worker earned less in a year than most Americans did in a week.

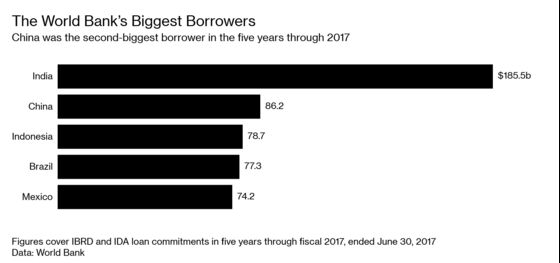

More than three decades later, China is the world’s No. 2 economy, with more than $3 trillion in foreign-currency reserves and development banks of its own that lend around the world. It’s also one of the World Bank’s biggest borrowers. But maybe not for long.

China’s huge trade surplus with the U.S., along with its plans to muscle into such areas as artificial intelligence, has raised hackles in Washington. President Donald Trump tends to talk about China in zero-sum terms: Its rise is a threat to America. Curtailing World Bank lending to China would fit with the administration’s efforts to contain Beijing’s economic power.

Even before the trade war, there were experts arguing that it’s time for Beijing to graduate from the ranks of World Bank borrowers. Those voices have notably included senior Treasury Department official David Malpass, the man most likely to become the bank’s next president.

In an interview with Bloomberg Television after being nominated by Trump last month, Malpass said the bank should follow through on a plan to cut lending to upper-middle-income countries such as China (others in the bracket that might be affected include Turkey and Brazil), so it could focus more resources on poorer nations.

Malpass has been blunter in the past. In November 2017, he said China has “other resources and access to capital markets” and doesn’t need help from development lenders. He has frequently scolded China for failing to live up to its market-reform promises. Late last year, he suggested to U.S. lawmakers that China was trying to make other countries dependent on its largesse through programs such as its “Belt and Road” initiative, a massive infrastructure plan that aims to revive China’s trading links with Central Asia, the Middle East, Africa, and Europe.

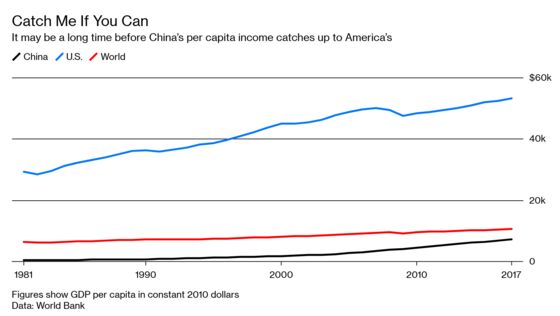

One counterargument is that while China is big, it’s still not rich. Output per capita is about one-sixth of America’s in dollar terms, and one-third if you measure by purchasing power. It “still has a lot of catch-up to do,” says Bert Hofman, the World Bank’s country director for China.

There are financial considerations, too. The bank’s biggest fund lends to middle-income countries. That fund typically makes a profit on each loan, by borrowing in bond markets at low rates and lending at a small margin. Part of the profits are funneled into the bank’s fund for the world’s poorest nations, which borrow from the bank at little or no interest. In other words, market-driven loans for countries such as China help the bank meet its lofty goals of reducing extreme poverty around the world. “The World Bank is a bank, and it needs to be lending profitably to at least some of its borrowers. China serves that role very well,” says Christopher Kilby, an economics professor at Villanova University.

Slashing credit to China could also have unintended consequences for the World Bank’s efforts to combat global problems such as climate change. And it could leave the bank on the outside looking in, without influence over such major Beijing initiatives as Belt and Road.

The China question cuts to the heart of the debate over what the World Bank should be. It was conceived during World War II to fund the reconstruction of Europe. Headquartered in Washington, the bank was seen by its biggest shareholder, the U.S., as an instrument of growing American power. Even then, some member countries saw a future in which it would be lending more broadly to help lift nations out of poverty. And that’s been the direction it has mostly taken since the 1970s. Still, the tug of war continued, with fiscal conservatives arguing that countries should eventually stand on their own feet. “It really is almost insane to be lending any money to China,” says Steve Hanke, a professor of applied economics at Johns Hopkins University who has known Malpass since the two served in the Reagan administration. “Money is fungible,” he says. When it makes its own loans to poorer countries, “China’s basically recycling World Bank money, and China gets all the credit for it.”

As part of a deal that paved the way for a $13 billion capital increase from members last year, the World Bank agreed to curb lending to “upper-middle-income” countries. Nations with per capita incomes above roughly $7,000 are supposed to start the process of “graduating.” If they still get loans, it should be to finance “global public goods” that markets can’t provide, according to the plan. The idea is that World Bank capital could be harnessed to fight problems that transcend borders, such as global warming.

Yet only 38 percent of World Bank loans to China went to public goods such as pollution control in the last three years, according to a new report by Scott Morris and Gailyn Portelance of the Center for Global Development. The rest went to such areas as transportation and agriculture that critics argue China could easily finance on its own.

World Bank loans to China are already falling—to $1.8 billion in the year through June 30, from $2.4 billion the previous year. Under Malpass, there could be a further squeeze. Plans for the bank to invest alongside China in some Belt and Road projects may also be shelved. Still, with other nations pushing back on the bank’s board and environmental questions rapidly rising on the list of global concerns, China’s graduation could be gradual.

But Morris says there are downsides to forcing China to quit cold turkey, including the risk that the bank will be worse-equipped to tackle the big global problems its members want it to target. “China is the world's largest polluter,” he says. —With Peter Coy

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Ben Holland at bholland1@bloomberg.net, Cristina Lindblad

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.