How China Is Planning to Rank 1.3 Billion People

China’s cabinet released sweeping plans to establish a countrywide social credit system by 2020.

(Bloomberg) -- China has a radical plan to influence the behavior of its 1.3 billion people: It wants to grade each of them on aspects of their lives to reflect how good (or bad) a citizen they are. Versions of the so-called social credit system are being tested in a dozen cities with the aim of eventually creating a network that encompasses the whole country. Critics say it’s a heavy-handed, intrusive and sinister way for a one-party state to control the population. Supporters, including many Chinese (at least in one survey), say it’ll make for a more considerate, civilized and law-abiding society.

1. Is this for real?

Yes. In 2014, China released sweeping plans to establish a national social credit system by 2020. Local trials covering about 6% of the population are already rewarding good behavior and punishing bad, with Beijing due to begin its program by 2021. There are also other ways the state keeps tabs on citizens that may become part of an integrated system. Since 2015, for instance, a network that collates local- and central- government information has been used to blacklist millions of people to prevent them from booking flights and high-speed train trips.

2. Why is China doing this?

“Keeping trust is glorious and breaking trust is disgraceful.” That’s the guiding ideology of the plan as outlined by the government. China has suffered from rampant corruption, financial scams and corporate scandals in its breakneck industrialization of the past several decades. The social credit system is billed as an attempt to raise standards of behavior and restore trust as well as a means to uphold basic laws that are regularly flouted.

3. How are people judged?

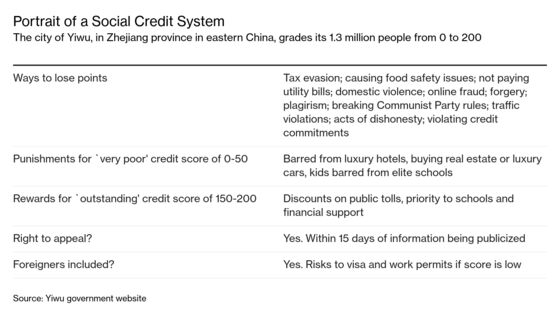

That varies place to place. In the eastern city of Hangzhou, “pro-social” activity includes donating blood and volunteer work, while violating traffic laws lowers an individual’s credit score. In Zhoushan, an island near Shanghai, no-nos include smoking or driving while using a mobile phone, vandalism, walking a dog without a leash and playing loud music in public. Too much time playing video games and circulating fake news can also count against individuals. According to U.S. magazine Foreign Policy, residents of the northeastern city of Rongcheng adapted the system to include penalties for online defamation and spreading religion illegally.

4. What happens if someone’s social credit falls?

“Those who violate the law and lose the trust will pay a heavy price,” the government warned in one document. People may be denied basic services or prevented from borrowing money. “Trust-breakers” might be barred from working in finance, according to a 2016 directive. A case elsewhere highlighted by the advocacy group Human Rights Watch showed that citizens aren’t always aware that they’ve been blacklisted, and that it can be difficult to rectify mistakes. The National Development and Reform Commission — which is spearheading the social credit plan — said in its 2018 report it had added 14.2 million incidents to a list of “dishonest” activities. People can appeal, however. The commission said 2 million people had been removed from its blacklist, while Zhejiang, south of Shanghai, brought in rules to give citizens a year to rectify a bad score with good behavior. And people who live in Yiwu have 15 days to appeal social-credit information that’s released by the authorities.

5. What part is technology playing?

Advances in computer processing have simplified the task of collating vast databases, such as the network used to blacklist travelers. Regional officials are applying facial-recognition technology to identify jaywalkers and cyclists who run red lights.

6. How have people reacted?

Local government officials in Suining, near Shanghai, scaled back their social credit system following pushback from local media and people. Yet educated, urban Chinese take a positive view, seeing social credit systems as a means to promote honesty in society and the economy rather than a privacy violation, according to a poll by Mercator Institute for China Studies. Human rights groups see this as a menacing development in a country where censorship of the media, internet and arts have been ramped up in recent years. President Xi Jinping’s government will be able to significantly expand its knowledge about what people — and even foreign businesses in China — do and think, wrote Mirjam Meissner, head of the economy and technology program at Germany’s Mercator Institute.

The Reference Shelf

- Keeping trust is glorious: China’s 2014 outline of its social credit system.

- China’s social credit system may be misunderstood, writes Bing Song, director of the Berggruen Institute China Center, in the Washington Post.

- Leiden University’s Rogier Creemers discusses the credit system in a podcast with Sinica.

- China’s heavy-handed approach is spreading, writes Bloomberg Opinion columnist Cathy O’Neil.

- Foreign Policy’s deep dive into Rongcheng’s social credit system.

- QuickTakes on the Uighurs and China’s great firewall.

--With assistance from David Ramli.

To contact the reporters on this story: Karen Leigh in Hong Kong at kleigh4@bloomberg.net;Dandan Li in Beijing at dli395@bloomberg.net

To contact the editors responsible for this story: Daniel Ten Kate at dtenkate@bloomberg.net, Grant Clark

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.