China’s Latest Crackdown Target Is Liberal Economists

China’s Latest Crackdown Target Is Liberal Economists

(Bloomberg Businessweek) -- Around 10 a.m. one day last summer, a low-ranking government official visited the offices of China’s most prominent free-market think tank to lodge a complaint. The scholars of the Unirule Institute of Economics were being too loud for the neighbors, the official said, and should consider finding an alternative place of business.

It was an odd allegation to make against a group whose idea of a wild night out might include a vigorous discussion of Hayek’s minor works, but no one at Unirule was surprised. For months, the organization had been harassed at its converted western Beijing apartment by a rotating cast of angry visitors: a landlord claiming it was violating the terms of its lease, tax collectors demanding to inspect financial records, bureaucrats citing violations of unspecified municipal regulations.

Unirule’s executive director, an amiable 64-year-old economist named Sheng Hong, had given his staff a set of instructions for such visits. They were to be polite, provide any requested files, and promise to address any genuine problems. His colleague Jiang Hao followed the script with the official, telling her the think tank would duly apologize to anyone who’d been disturbed and would be quieter in the future. His promises seemed to be successful, and the visitor departed.

Jiang was at his desk that afternoon when Unirule’s landlord arrived, accompanied by a property manager and a team of construction workers carrying power tools, a welding torch, and a reinforced metal door. Security doors aren’t uncommon in Chinese residential buildings, and at first Jiang wasn’t particularly alarmed. Then something astonishing happened: The workers began welding the door across the entrance to Unirule’s office, sealing Jiang and several colleagues inside. He protested and took photos, but the workers refused to stop. Not knowing what else to do, Jiang called the police. Soon, officers arrived and persuaded the building caretaker to let the Unirule staffers out. When they returned the next day to collect their belongings, the metal door was secured in place again. A few days after that, two security cameras were set up outside.

Unirule is the brainchild of Mao Yushi, a respected 90-year-old economist who was among the first scholars to spread free-market ideas such as deregulation and privatization within China. Until recently, the think tank was one of the country’s more influential nongovernmental organizations, benefiting from the relative liberty granted to economics since the rule of Deng Xiaoping, who once declared that he didn’t care “if the cat is black or white, so long as it catches mice.” So long as they stayed mostly clear of politics, scholars were free to discuss Western thinkers and how their ideas applied to China. The result was a vibrant intellectual community that interacted with government decision-makers, providing data-driven reality checks for officials with little experience outside the Communist Party.

That space has shrunk drastically under President Xi Jinping, who has forcefully reasserted the party’s power and the state’s economic role, and has attacked the civil society that emerged under his predecessors. A crackdown on dissent that began shortly after he took office in 2012 has seen Unirule, which has a small but consequential following among entrepreneurs and academics, hounded almost into oblivion. Its Chinese website and social media accounts have been shut down, its events broken up, and some of its staff barred from traveling abroad.

As China navigates the challenges of a slowing economy and a bruising trade war with the U.S., some foreign observers have become alarmed. “Economic decision-making has become incredibly personalized under Xi. An economist who raises questions may be seen as raising questions with Xi personally,” says Julian Gewirtz, a researcher at Harvard and the author of Unlikely Partners: Chinese Reformers, Western Economists, and the Making of Global China. He calls the resulting chill “a profound source of risk for China’s future.”

Unirule found another office after its sudden eviction, and so far it has survived, if just barely, thanks to its prominence abroad and the prestige of Mao, who retains quiet admirers in China’s establishment. But the think tank’s experience demonstrates just how little scope for independent inquiry remains, even on critically important economic issues such as fiscal policy and the sustainability of the country’s vast archipelago of state-owned enterprises. In Xi’s China, it turns out, practicing the wrong kind of macroeconomics can be a thought crime.

China in the 1980s was a place of intellectual ferment, with previously banned ideas being widely discussed—at first gingerly, as citizens who came of age during the Cultural Revolution tested their new boundaries, then with increasing openness. At a time when Ronald Reagan and Margaret Thatcher were transforming the economies of the U.S. and U.K., these ideas included the theories of thinkers from the Chicago School, who argued that free markets are invariably better at creating wealth than governments.

Such views sometimes gained a remarkable degree of official sanction in China. The government invited archlibertarian Milton Friedman to Beijing in 1980 to get his advice on how to curb inflation resulting from the relaxation of state price controls, for example. (Admittedly, his opinion wasn’t well-received.) Over the next several years, China also began allowing more academics to study abroad. They got direct experience of Western prosperity, and many returned with opinions on how to replicate it.

Mao Yushi was among the fascinated. Born in Nanjing and sent as a young man for “labor reform” in rural Shandong, he spent most of his career as an engineer for the state railways, driving trains and working on engine designs in a Beijing office. As the country opened up, he began reading widely in economics and attending lectures by the foreign academics who were visiting more and more frequently. He was struck by the ideas of Friedman and others of the Chicago School. Their theories might have translated in China into reducing the state’s role in setting prices and allocating investment, or into moving faster to chip away at state monopolies in industries such as telecommunications and airlines—emulating the free-market-oriented policy overhauls under way in the West.

Despite being entirely self-taught, Mao took up a position in 1984 at the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences, a degree-granting government research agency that employed much of the economics elite. The next year he published his first book, The Mathematical Foundation of Economics: The Principle of Optimal Allocation. Dense with formulas, it was well outside the Chinese academic norm; most contemporary economists were trained to think like Marx and Engels, not to do math. A year later, Mao was accepted as a visiting scholar at Harvard, where he was perplexed by a class on taxation. In China, where virtually all companies belonged to the state, the tax system was still primitive.

At CASS he encountered Sheng, a doctoral student similarly interested in free-market ideas—particularly those of Ronald Coase, a British theorist known for his work on why companies, not individuals, come to dominate economies. CASS was an elite institution, but its perks were minimal. Salaries were paltry, and funds for research or overseas travel were severely limited. Meanwhile, in broader society, serious money was flowing.

In 1992, Deng embarked on his so-called Southern Tour, an extended trip to Guangzhou, Shenzhen, and Shanghai that marked the end of a post-Tiananmen relapse into communist orthodoxy. Mao and Sheng, feeling that CASS was out of step with the booming economy outside its walls, decided it was time for a change. The following year they created Unirule—the name an allusion to a Chinese poetic concept suggesting that “universal rules” govern human interactions—to serve as a think tank and for-profit consulting firm. The arrangement’s advantages were more than financial. The legal status of NGOs in China has always been uncertain, and incorporating as a business added a layer of protection from officials.

To get Unirule up and running, the pair turned to a sympathetic businessman, who provided 900,000 yuan (about $160,000 at the time) in capital. The early days were hard going. Mao at one point traversed Beijing on a bicycle selling copies of one of Unirule’s first publications, a magazine called Overseas Business that targeted the country’s new executive class.

Gradually, Unirule developed links to academics abroad and established itself as a respected source of analysis on China’s growing economy. It also began making decent amounts of money, in many cases by selling its services to government officials eager to learn about capitalist ideas. One early client was China Unicom, a state-owned telecommunications giant for which Unirule prepared a report on liberalizing the nascent mobile market. Another piece of work, for the rail ministry, analyzed potential pricing reforms. At one point, Mao and Sheng were commissioned to devise an economic strategy for the remote city of Kashgar, in the western region of Xinjiang. Their proposal—that the ancient trading hub reestablish links with the countries along the historic Silk Road—anticipated the “Belt and Road” initiative, Xi’s signature foreign economic policy.

As Unirule entered something resembling the intellectual mainstream, Mao and Sheng began to feel comfortable, even lucky, to have a front-row seat for one of the most dramatic economic transitions in history. “This was a really rare opportunity to observe a planned economy transforming into a market economy,” Sheng recalls. “You couldn’t really research that in America.” Emboldened, they called repeatedly for the state to move further and faster to open up the economy—mild advocacy by Western standards but potentially dangerous in China. While plenty of Chinese thinkers were endorsing aspects of free markets, Unirule’s embrace of essentially the whole capitalist system was unusual. To Mao and Sheng, this was a matter of intellectual honesty.

Unirule’s freedom shrank somewhat in the mid-2000s, when President Hu Jintao moved to curtail criticism of state policies. But the organization remained a vital force, with as many as 30 staff members and annual revenue that exceeded 5 million yuan in 2004. In 2011 it thrilled entrepreneurs and infuriated government officials by publishing a widely read report arguing that virtually all of China’s state-owned enterprises would be unprofitable without favors such as low-interest loans and cheap land. That year, Mao also published an essay, “Returning Mao Zedong to Human Form,” that called the late dictator “childish” and argued that his “capacity for destroying the country was higher than anyone.” In a nation where the founding leader’s image adorns most every bank note, it was provocative stuff.

Even as Unirule’s influence grew, attitudes toward Chinese economic liberals were beginning to turn. In 2012 the Cato Institute, Washington’s top libertarian think tank, presented Mao—the scholar, not the revolutionary—with its Milton Friedman Prize for Advancing Liberty, an honor given previously to Peter Bauer and Hernando de Soto, both internationally prominent economists. During the presentation at the Washington Hilton, a protester representing the growing ranks of “neo-Maoists”—Chinese activists drawn to the hard-line ideologies of the early People’s Republic—burst into the ballroom, shouting and waving signs labeling the economist a “traitor” who “serves rich Americans.”

Back in Beijing, the government was preparing to hand leadership to Xi, a dedicated communist who’d spent his entire adult life in party institutions. As he consolidated power, sidelining critics from both the right and the left and extending the reach of party propaganda, Unirule found itself targeted. At first, it was bit by bit. Starting in about 2015, some of Sheng’s and Mao’s posts on social media platforms WeChat and Weibo (where Mao had more than 2.6 million followers) began disappearing. Venues around Beijing canceled Unirule seminars and panel discussions, citing burst water mains, mysterious power cuts, or other excuses.

No one from the government ever informed Unirule of what it had done to offend, but Sheng and Mao hardly needed to be told. Many of Xi’s policies were focused squarely on reestablishing the centrality to economic life of the state in general and state-owned companies in particular. And other sources of independent research were in even worse trouble. A prominent legal and economic think tank, the Transition Institute, was shut down after officials said it lacked proper registration. Consensus Net, a website that published essays and commentaries by academics, went permanently offline.

In January 2017 Unirule’s blacklisting became almost complete: Across a few hours, its website and social media accounts disappeared from the Chinese internet, again without explanation. Later that year, the institute was pressured into leaving its office near Beijing’s business district, moving from there to the apartment where its staff would be barricaded in. (The State Council, China’s cabinetlike decision-making body, didn’t respond to a request for comment on the government’s moves against Unirule.)

Last November, the state finally made clear to Sheng what it thought of him and his fellow free marketeers. He was at Beijing’s main airport, checking in for a flight to Boston, where he’d been invited to speak at a Harvard symposium marking the 40th anniversary of China’s economic liberalization. When he tried to scan his documents at the automatic passport-control gate, it refused to open. Confused, Sheng asked a border officer for an explanation. After consulting a computer, the man delivered the news: By order of the State Council, Sheng had been banned from leaving the country. He was considered a threat to national security.

What’s left of Unirule operates from an apartment abutting a busy rail corridor about 15 miles north of central Beijing. It’s accessed through a dingy hallway with dirt-streaked, peeling white paint; above the call button for the rattling elevator, someone has scrawled an advertisement for a local prostitute. Unirule is in a cramped unit on the 10th floor. During a recent visit, Jiang, the economist who called the police last summer, provided what passed for a tour, pointing out bookshelves sagging beneath Unirule studies and works by foreign economists. “The only Communist Party document we have here is the constitution,” he said with a chuckle. Most of the 10-person staff works at bare tables in a converted living room. Jiang, who wore a faded plaid shirt and wrinkled blue trousers held up by a frayed leather belt, conceded that the job now entailed significant personal sacrifice. “All these people,” he said, “are strong believers in freedom.”

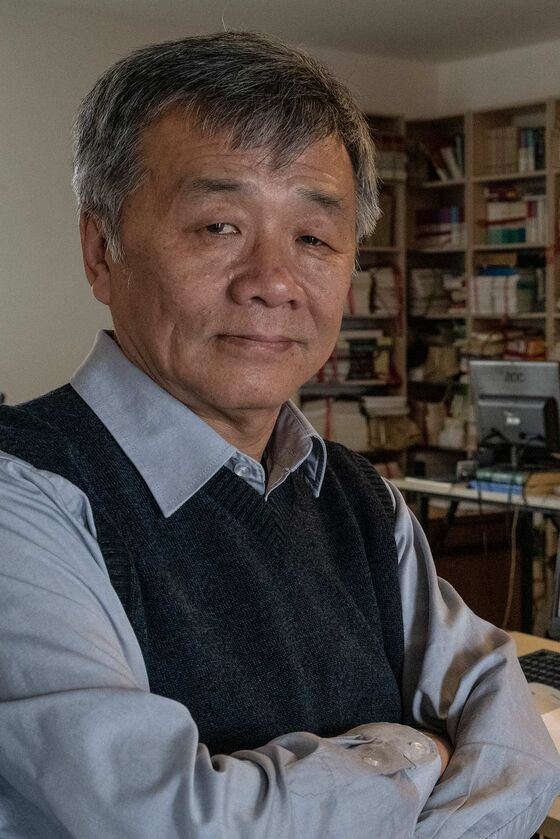

Sheng’s office is in an old bedroom crowded by two wooden desks intended for a larger space. The leather armchairs reserved for visitors are similarly disproportionate and show signs of hard use, with one armrest split to bare the stuffing inside. “There are a lot of people interested in liberal ideas, especially private entrepreneurs and middle-class professionals, and if it weren’t for the pressure from the government, we would have more interest,” Sheng said from behind one of the desks. “Xi wants to control everything, even what he can’t really control,” he added. “Our voice is very tender, very peaceful, but still he doesn’t want to hear it.”

Sheng, who’s compact and wiry, with thin salt-and-pepper hair, argued that Unirule remains relevant—publishing papers, meeting with foreign academics, organizing seminars and a reading group devoted to Friedrich Hayek and other classical liberals. The organization has also quietly continued offering economics classes to businesspeople, though attendance has dwindled in light of the government’s disapproval. Financially, Unirule is sustained by revenue from those classes and the generosity of a small group of benefactors, none of whom are willing to reveal their support.

Xi is arguably China’s most dominant leader in decades, and the state periodically shuts down troublesome organizations and imprisons people it deems threatening. Yet while Sheng (and now Jiang) can’t leave the country and the staff gets occasional requests to come “for tea” with police or intelligence agents, they’re otherwise walking free. To Sheng, the reason for Unirule’s tenuous survival is simple: Even in China, even under Xi, there are limits. Unirule has been careful to stay within the letter of every regulation it can, and an outright ban might produce international protest. “The government wants to have a good surface presentation,” he said. “They would like us to disappear by ourselves.”

That Unirule still exists probably also owes something to Mao’s cachet. His works were common on Chinese university campuses in the 1990s and 2000s, studied by a generation that’s since fanned out into high-level jobs in business and government. And at a time when Beijing is eager to repair badly frayed ties with a Republican-led U.S. government, being the favorite Chinese economist of Cato, an influential Beltway think tank co-founded by a Koch brother, probably counts for something.

Mao lives in western Beijing, in a complex of squat apartments reserved for government workers and retirees. (He qualifies thanks to his father’s career as a bureaucrat.) Government minders patrol outside his flat, asking visitors to identify themselves and sign in on a clipboard. Before Mao began an interview in a sitting room crowded with framed accolades and photos of trips abroad, his wife, Zhao Yanling, asked that “sensitive topics” be avoided as much as possible. “I want to maintain the little bit of freedom we still have,” she later explained.

Mao, who was seated next to her on a bulky armchair, took little heed, speaking with a frankness that might land a less esteemed public figure in jail. “The freer a country is, the richer it is. There are no unfree countries that are rich,” he said in Chinese. Alert and focused but clearly frail, he wore gray long-underwear bottoms and a navy cardigan over a light blue button-down shirt. “The idea of communism is a tragedy, a disaster,” he went on. “All countries that embraced communism have failed, without exception.” Yet though Mao has continued to call for China to transition to a more unapologetically capitalist system, he doesn’t advocate regime change or anything like it. To emphasize the point, he pulled out a yellowed copy of the constitution of the People’s Republic, which nominally guarantees freedom of speech and assembly. “Everything I do is according to the constitution,” he said.

Mao is essentially retired, and he sometimes spoke about Unirule as though it no longer existed, at one point describing it as having been “canceled.” But he expressed confidence that China would bend toward openness and liberalization as the contradictions of a state-dominated economy become irreconcilable. “For the long term, you can very clearly see that the public sector has major problems and the private economy is very dynamic,” he said. “For a market to be efficient, it must respond to market forces, not government.”

China’s current leadership might disagree, he recognized. “But I really believe the direction of the world is toward liberalization, not toward communism.” The country, in his view, can’t forever violate what he cast as near-immutable laws of human relations—his inversion of the Marxist notion that capitalism’s inherent flaws will lead inevitably to its replacement. The trade war instigated by President Trump, he asserted, is less about specific policy disputes than the fundamental tension between antithetical philosophies, one of them doomed to fail. “The contradiction between the countries has to do with their systems, not trade,” Mao said. And in China, “the system needs to change.”

In economic terms, Xi is hardly taking China back to the Cultural Revolution. Private companies and their leaders continue to be powerful actors, and in recent months he’s made several statements of support for markets and entrepreneurship. Partly in response to pressure from the White House, China’s rubber-stamp legislature passed a long-awaited law on foreign investment in March, promising to thin the web of restrictions that effectively exclude overseas companies from much of the economy.

Xi’s overall strategy, however, is unprecedented: to harness the wealth-generating potential of the market while steadily restricting the sources of information and analysis on which the market depends. The media has been almost entirely muzzled, in line with the president’s 2016 pronouncement that the primary role of the press is to serve the party. Many NGOs have ceased operations since a 2017 law required them to find official sponsors or face closure. Access to information from the uncensored non-Chinese internet, long quietly tolerated for its utility to businesspeople and academics, has been severely curtailed. Government economic data remains the object of significant suspicion from overseas analysts. And as Sheng and Mao have learned, publicly challenging official narratives from within China is almost guaranteed to attract a severe response.

Among researchers and government officials who might otherwise publicly question policy, these measures are having a predictable effect. “Very few younger economists are now willing to criticize the macro picture,” says Victor Shih, a professor at the University of California at San Diego who studies Chinese banking and fiscal policies. In private, “there’s still a debate, but none of them would ever put these thoughts into a journal article.” Such repression is of course damaging China’s scholarly output. But it could have broader consequences, too. The fear is that, with investors essentially forced to take the Communist Party’s word on the state of the economy, unseen distortions could build up until a crisis arrives. And a crisis for China’s economy would be a crisis for the world.

Quixotic though it may seem, Unirule’s remaining staff say they’re determined to mitigate that risk by carrying on until the ideological tide turns. Even with their operations badly hobbled, Sheng and his colleagues continue to publish. Their latest projects concern how the government allocates resources and how access to mobile broadband is transforming China’s economy. Another, more provocative initiative will examine how to realize the constitution’s Article 35—the section promising freedom of speech. “We will continue to work,” Sheng said, “until it’s impossible.” —With Xiaoqing Pi

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Jeremy Keehn at jkeehn3@bloomberg.net

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.