China’s Government Is Letting a Wave of Bond Defaults Just Happen

Though many companies are still state-backed, policymakers are getting more comfortable with defaults.

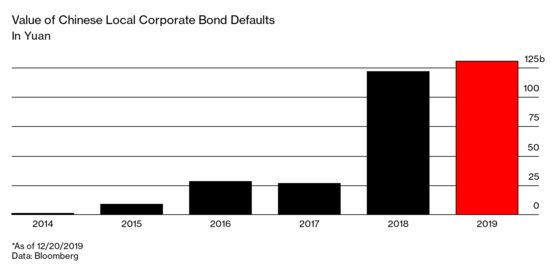

(Bloomberg Businessweek) -- China’s had another record year of corporate bond defaults. That’s not a crisis. It’s a plan.

A decade ago, defaults almost never happened, but that wasn’t because companies in China were always healthy. It was a reflection of the tightly controlled financial system, where companies were often linked to the government and bonds were largely bought by state-owned lenders. Authorities have often stepped in to ensure that financially troubled enterprises didn’t crash into default, out of concern over social unrest in the event of job losses or missed payroll payments.

This system imposed little discipline on borrowers. Now global investors are coming into China’s bond market. Though many companies are still state-backed, policymakers are getting more comfortable with defaults. Without them, bond buyers would have little incentive to make a careful assessment of a company’s creditworthiness.

But rising defaults also mean that global investors have to abandon some assumptions about which borrowers are safe. There are some nasty surprises on the long list of companies that have either defaulted or have seen their bond prices plunge. Among them: a would-be Wall Street-style investment bank endorsed by China’s premier and two technology companies connected to top universities. In December, a commodities company called Tewoo Group Corp. delivered the biggest dollar-bond default in two decades by a state-owned enterprise. That event “could prove a turning point,” says Todd Schubert, a managing director for fixed income at Bank of Singapore. It’s getting more dangerous to count on some companies being, in essence, too connected to fail.

Tewoo’s businesses include mining, logistics, and infrastructure. Based in the industrial city of Tianjin, southeast of Beijing, the company defaulted when its debt had to be restructured, with bondholders being offered as little as 37 cents on the dollar. After news of Tewoo’s debt restructuring plan, Moody’s Investors Service warned investors that state-owned enterprises that aren’t “strategically important” to the government would be less likely to get bailouts.

But figuring out which companies still qualify as strategically important won’t be easy. “How many defaults can the system handle will be a question confronting the leadership in 2020,” says Andrew Collier, a managing director at Orient Capital Research. Hundreds of billions of dollars of debt could potentially become problematic. That includes credit extended to property developers and local government financing vehicles, which fund infrastructure projects. Many lack sustainable sources of revenue, and China’s economic slowdown to a pace of around 6% just makes things worse.

“It’s incredibly difficult to do true credit analysis for most borrowers in China,” says Michel Lowy, chief executive officer at Hong Kong-based banking group SC Lowy. “Ultimately it has a lot less to do with the quality of the businesses that are underneath and a lot more to do with who is supporting them, who owns them, and what is the goal of their setup.”

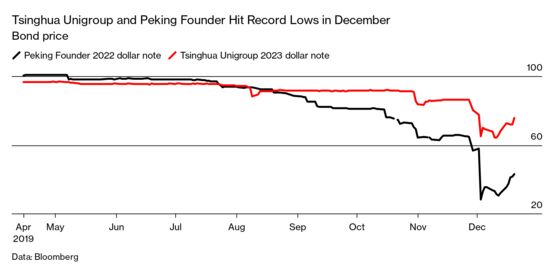

A lesson in how dicey bets on state support can be came in the second half of 2019, when the bonds of two state-backed tech companies tumbled in value (though they have not defaulted). Tsinghua Unigroup Co. is a chipmaker at the forefront of Beijing’s campaign to achieve global dominance in technology. Its finances had deteriorated sharply in the past three years as it borrowed to invest and make acquisitions, but it was linked to Tsinghua University, which counts President Xi Jinping and his predecessor Hu Jintao as alumni. The other company, Peking University Founder Group, a sprawling conglomerate with medical and internet businesses, is tied to Peking University, another elite school. In the past, the companies’ public ownership and connection with the tech sector might have meant their bonds were immune to default concerns.

Not so. A government push to separate academic institutions from their business ventures put a cloud over the two companies. The fact that they don’t report to China’s main state-assets overseer, but to the Ministry of Education, might also have left questions in investors’ minds. “Persistent uncertainty over the future ownership of these firms has instilled doubts over their financial position—especially since they are capital-intensive businesses with high profit uncertainty,” says Wei Liang Chang, a macro strategist at DBS Bank Ltd. Of the two businesses, investors are more worried about Founder, but the companies’ bonds tend to tank in tandem. The bonds have recovered some of their earlier losses. A spokeswoman from Unigroup said the firm is confident of meeting all bond-payment obligations. Peking Founder didn't respond to a request for comment.

Perhaps none of the year’s subsequent troubles should have come as a surprise, given how 2019 began with a delayed payment by one of China’s largest private investment companies. China Minsheng Investment Group Corp. was founded in 2014 with the endorsement of Premier Li Keqiang, the country’s No. 2 official. CMIG had run up a lot of debt—about $34 billion as of last year—and had binged on assets, from London property to the solar-energy business to an insurer in Bermuda.

Since the delayed payment on a domestic bond in January, CMIG has been scrambling to sell assets and slashing executive pay. (In April, the company said default provisions had been triggered on two of its dollar bonds.) The company is making every effort to promote an asset, debt, and equity restructuring, it said in an emailed comment in November.

The investment bank became a statistic in the record $21 billion of defaulted bonds from Chinese issuers this year. The vast majority of that has been in the onshore market—bonds denominated in yuan and held mainly by domestic investors—but the rise in defaults in 2019 suggests more trouble could be in store in 2020 for the dollar-based debt that draws more international investors. “The willingness to pay is clearly now in question for large parts of the offshore bond market,” says Owen Gallimore, head of credit strategy at Australia & New Zealand Banking Group Ltd. —With Molly Dai and Yuling Yang

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Pat Regnier at pregnier3@bloomberg.net, Neha D'SilvaChris Anstey

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.