China’s Vast Network of Gray-Market Shoppers Grounded by the Pandemic

China’s Vast Network of Gray-Market Shoppers Grounded by the Pandemic

(Bloomberg Businessweek) -- Vivian Li, a stay-at-home mother in Shenzhen, used to make weekly trips abroad, leaving her husband in charge of their toddler and traveling to Hong Kong or Tokyo with two empty suitcases. She would fill them with Lancôme eye creams, Pola shampoos, Louis Vuitton handbags, and other products that in China were either much pricier or simply unavailable—sometimes clearing out the store shelves for items that internet celebrities had recommended. Then she would return home and send the goods via express delivery to clients who’d hired her to shop for them. Working as a personal shopper, or daigou, was a lucrative job for Li, 28, who could make more than 30,000 yuan ($4,626) a month from her travels.

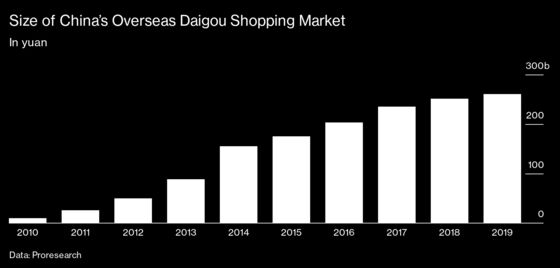

This army of gray-market surrogate shoppers has long been a feature of China’s retail sector, serving consumers who crave items that aren’t available locally or are sometimes significantly more expensive in the country. Despite the government’s best efforts to kill off the daigou trade through stricter customs checks and eased taxation rules for legitimate cross-border e-commerce channels, it grew to $40 billion in revenue in 2019, according to the consultancy Proresearch in Beijing.

Then came Covid-19. China slammed its borders shut to keep out the virus, putting a halt to most overseas travel—and the business of Li and other daigou operators. Although she places some orders through overseas partners, without Li on-site to personally vouch for the provenance of the products, many clients don’t trust the authenticity of the goods. That skepticism has led her to lose more than half her business. “Many of my daigou peers have exited the market,” she says. “I just hang in there hoping the border can reopen soon, but the longer we wait, the more likely my clients have found other channels and leave forever.”

The collapse of daigou has also left businesses, whether infant formula makers or cosmetics retailers, struggling. Before the pandemic, some foreign companies grew rapidly thanks to the trade. By selling to personal shoppers and letting them handle the delivery back to China, they didn’t have to invest in building local retail operations of their own. Companies could also avoid requirements to comply with Chinese labeling and packaging laws.

“The whole daigou sector has dried up,” says Sage Brennan, co-founder of China Luxury Advisors, a consulting company in Los Angeles. “A lot of consumers have gotten into more legitimate cross-border e-commerce, and that becomes easier as time goes on than relying on the gray markets.”

Companies that counted on daigou sales are now saddled with excess inventory. “Daigou is unlikely to reach its heyday market size anymore even after the pandemic eases,” says Ethan Ye, a principal in Shanghai for consultants Oliver Wyman. One reason: Luxury brands that focused on expanding in China during the pandemic are putting more pressure on daigou rivals, says Max Peiro, chief executive officer of Re-Hub, a data analytics company in Shanghai. “More and more brands are taking active measures” against the gray-market sellers, he says. “They realize this is a situation they need to try to mitigate.”

One of the most popular daigou products is infant formula, and during the offshore shopping industry’s peak time, from 2010 to 2019, Australia, Hong Kong, and other places restricted the number of containers individuals could purchase to prevent daigou shoppers from buying up all the supply. But A2 Milk Co. in New Zealand downgraded its forecast in May for the second time in five months, after its revenue in Australia and New Zealand fell about 30% in the second half of 2020 because of disruption to daigou channels. The share price of the company, among the largest on New Zealand’s stock market, has fallen more than 60% over the past 12 months, compared with an 8% rise for the benchmark index.

The outlook for A2 and rivals Danone SA and Reckitt Benckiser Group Plc is grim as the delta variant spreads and travel curbs persist. “The longer this happens, the harder it will be for Danone, Reckitt and A2 Milk to rebuild China sales as their local customer bases shrink,” Bloomberg Intelligence analysts Catherine Lim and Kevin Kim wrote in a report published on July 5.

Even before the pandemic, there were signs the business faced tougher times. Worried about lost revenue, China’s government tightened customs checks and tax regulations. Chinese consumers also were gaining more options domestically, a result of the proliferation of cross-border e-commerce services and duty-free malls.

Some customers might be lost for good as travel curbs change consumer behavior. About 60% of Chinese consumers last year used cross-border e-commerce platforms, led by Tmall International and JD International, according to IResearch. Those online retailers had import sales of more than 200 billion yuan in 2020, and their sales should grow about 30% annually over the next two years, even as the pandemic eases, IResearch says.

Japanese drugstore operator Tsuruha Holdings Inc., popular among daigou customers for its beauty and personal-care products, is turning to online platforms. In September it opened a store on WeChat, the app that Tencent Holdings Ltd. owns, to deliver products directly to customers in China. At the top of every product page of its WeChat store are the Chinese words “Shipped from Overseas, Authenticity Guaranteed,” because even the most price-sensitive daigou consumers worry about fake products and shoddy quality.

To discourage customers from going back to daigou, some brands are offering more services designed to build longer-term relationships with individual consumers. Japanese cosmetics maker Shiseido Co. has appointed beauty consultants to provide one-on-one services to its Chinese VIP members and to send them free product samples. Shanghai-based Ushopal, founded in 2017, works with more than 3,000 online influencers and helps organize popup stores to promote items such as perfume from Juliette Has a Gun and lipstick by Suqqu. Customers placing orders via Ushopal’s cross-border e-commerce platform can get delivery in four hours from its Shanghai-area warehouse.

For luxury brands in Europe, daigou hindered efforts to build relationships with customers; the buyers purchased in bulk for clients, so the brands couldn’t identify them. “It’s all about knowing the local client now and establishing a long-term relationship,” says Jonathan Siboni, CEO of data intelligence firm Luxurynsight in Paris. “It’s more than just a one-off handbag sale.”

Some brands have raised prices in Europe to narrow the advantage over the prices of their goods in China, undercutting one of the main reasons the daigou started in the first place. “You don’t buy with daigou when you only have a price differential of 15% to 20%,” Siboni says. “There was a rationale if the differential was 50%, but that’s no longer the case.”

Still, Li and other daigou say they expect at least some customers will return. A Japanese beauty retailer Li works with is getting ready, opening several warehouses in China for some hot-selling products to shorten the delivery time to consumers. Li’s job will be to drum up business through her social network. It won’t be like the old days of overseas shopping, she says, but that’s all right. “Most customers are fine to pay” the import duties, Li says. “They still can’t find some of the products in domestic channels anyway.”

©2021 Bloomberg L.P.

With assistance from Bloomberg