China’s Hit Video Site Serves Teens Anime With a Side of Marx

China’s Hit Video Site Serves Teens Anime With a Side of Marx

(Bloomberg Businessweek) -- Like many Chinese teenagers, Shan Bingxin turns to Bilibili to alleviate his pandemic ennui. For about three hours a day, the 15-year-old scours the online entertainment hub for anime clips, gaming tutorials, and news. But increasingly, the site that began as a forum for gaming- and animation-obsessed geeks is emerging as an unlikely hotbed for current affairs—with an ever more nationalistic bent.

Alongside typical posts about Grand Theft Auto or the Japanese manga series Naruto are clips generated by government-sanctioned influencers and hawkish news outlets. Shan recently watched a livestream showing Wuhan rapidly erecting temporary hospitals for virus patients, which filled him with pride in his country. Another clip showing U.S. President Trump calling Covid-19 the “Chinese virus” infuriated him.

Beijing is using popular culture to appeal to young people by plastering Communist Party slogans onto video games and enlisting boy bands as role models. One anime series from last year depicts the life of German socialist philosopher Karl Marx, whose theories are taught widely in Chinese schools. The show, co-produced exclusively for Bilibili by several state institutions, including a provincial propaganda department, depicts the young Marx as a typical Japanese manga-style protagonist.

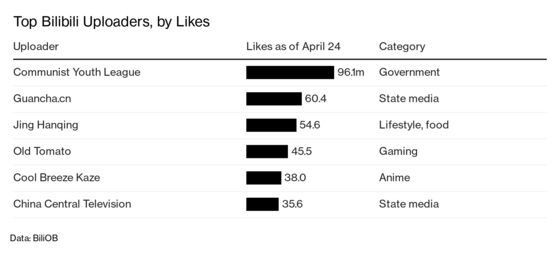

The Communist Youth League and other groups have been flooding Bilibili with virus-related conspiracy theories and fanning anti-American sentiment. The Youth League, the party’s branch for younger members, is among the site’s top seven creators, with about 6 million followers; it gets the most likes of any contributor, according to data tracker BiliOB. Part of the platform’s allure to state-sponsored programs is the credibility it has, being backed by some of China’s biggest public companies, such as Tencent Holdings Ltd. and Alibaba Group Holding Ltd. Electronics maker Sony Corp. of America said this April it will invest about $400 million in it.

While propaganda promoters are also active on other social channels, such as microblogging site Weibo and mini-video app Douyin, campaigns appear to be more effective on Bilibili because of the nature of its 130 million active users. “Bilibili is uniquely positioned in China, as it’s the only video platform focusing on both high-quality and user-generated content,” says Gao Bowen, an analyst with Sinolink Securities. “Its Gen Z users have created a very interactive community atmosphere.”

When it started almost a decade ago, Bilibili was a digital hub for ACG, or anime, comics, and games. Since then it’s morphed into a YouTube-style service with wider appeal. Premium members pay about $15 a year so they can watch anime releases early. Now there are other types of offerings. Some of the site’s most popular video topics in recent months include: how the coronavirus might have originated from a leak in a secret U.S. military lab; why Taiwan’s push for independence will lead Beijing to war; and how Trump is trying to maintain American tech supremacy by suppressing Huawei Technologies Co. A spokeswoman says that Bilibili hosts a variety of content to meet users’ diverse interests, and that “keeping our community safe and enjoyable is a top priority.”

The site’s young audiences are feeling especially good about their country “as a result of pride in the way the nation has contained the virus and also in response to racism toward Chinese abroad and the every-country-for-itself mentality,” says Mark Tanner, founder and managing director of China Skinny, a Shanghai-based consultancy.

A video montage by the Youth League about protest violence in Hong Kong has garnered almost 9 million views since it was posted in November, making it the League’s all-time favorite on the website. On YouTube, which deemed the clip unsuitable for minors, it’s gotten just 7,000 views. In March the Youth League’s unit in Guangdong province recruited a group of Bilibili vloggers to create an anime music video celebrating women’s empowerment on International Women’s Day.

Touting patriotism can also be fun. One of the most well-received Chinese anime series on Bilibili portrays the country as an innocent-looking but tough rabbit and the U.S. as a bald eagle. In one episode about the Korean War, the rabbit dutifully stands by for the order to attack despite the blistering cold. Meanwhile, just a couple of miles away, the eagle whines about having to eat canned meat and the lack of barbecues. (Bilibili is an investor in the studio that produced the show.)

The company has discovered that content that champions China brings traffic and marketing dollars. A New Year’s Eve gala co-hosted with state news agency Xinhua and sponsored by Alibaba attracted more than 80 million simultaneous viewers. Along with an orchestra playing Harry Potter theme music and people dressed as elves and warriors, it featured a chorus of soldiers singing a patriotic anthem about fighting off Japanese invaders during World War II. Online viewers flooded the livestream with the floating on-screen comments, or “bullet,” a Bilibili feature, declaring their gratitude for having been born Chinese. The segment elicited more audience messages than a performance by pop idol Kris Wu.

Bilibili reported a bit more than 2 billion yuan ($282 million) in revenue in the fourth quarter of 2019, up 74% from a year earlier. The bulk of that came from mobile-game-related sales, followed by livestreaming and advertising.

Still, its success hasn’t been entirely smooth. In 2018 it was removed from China’s major Android app stores for a month after regulators expressed concerns over inappropriate material, prompting the company to double the number of content-moderation staff and pledge to recruit 36,000 “volunteer” censors. And not all efforts to boost national pride work. In February, the Youth League made its own virtual avatars for Bilibili, expecting that the duo of cartoon siblings would inspire a huge following just like real-life pop idols. But they were pulled offline from Bilibili and other sites, prompting concern that the government was subverting anime culture for political purposes. Some users have been put off by the nationalist themes. Cheng Yingying, a 20-year-old Chinese college student in California and premium Bilibili user, unfollowed the Youth League’s account after it spammed her. “I’m here for fun. I don’t want to get patriotic education while I’m watching anime,” she says.

The cozy arrangement among the platform, propagandists, and advertisers comes with bigger risks. Bilibili, for example, could spawn “some blindly xenophobic nationalists” among young people, says Fang Kecheng, an assistant professor of communication and journalism at the Chinese University of Hong Kong. “If they develop worldviews based on the limited information there, it’s clearly not a good thing for China’s relations with other countries—especially with the U.S.”

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.