China Loosens Urban Residency Restrictions to Spur Growth

China Loosens Urban Residency Restrictions to Spur Growth

(Bloomberg Businessweek) -- In China, where you’re born can make all the difference.

The nation’s residency permit, known as the hukou, defines a person’s entire life. Since the system’s introduction six decades ago, the hukou has determined where people can live, where they can work, and where their children go to school; it can even influence whom they choose to marry.

At its inception in 1958, the hukou provided China’s policymakers with a means to regulate the movement of people to further important national objectives. The system supported the twin goals of farm collectivization and rapid industrialization during the Great Leap Forward. Yet today there’s a growing consensus that the maroon-covered documents may be holding back the country. In addition to helping institutionalize a yawning gap in living standards between rural and urban residents, restricting labor mobility may prove damaging to the economy over the long term.

President Xi Jinping has made overhauling the hukou a key policy goal and even argued for abolishing it altogether in his doctoral thesis almost two decades ago. A policy statement issued on Dec. 25 by the State Council, China’s cabinet, included a pledge to eliminate the registration system in cities with fewer than 3 million residents and relax it in cities with populations of 3 million to 5 million. For larger cities, such as Beijing and Shanghai, the household registration system will be simplified, it said, without giving details. These guidelines echo those published by the National Development and Reform Commission in April.

“This is by far the boldest and the most significant move to remove the institutional barrier responsible for maintaining the two classes of citizens within the same country, the most consequential original sin created during China’s socialist planned economy era,” wrote Wang Feng, a sociology professor at the University of California at Irvine who’s studied China’s urbanization for decades, in an exchange on WeChat, a Chinese messaging app. “Such a move will no doubt increase labor mobility, usher in new economic dynamism, and reduce a type of social inequality that has plagued China for over half of a century.”

The proposed changes also may help counteract the economic drag from a vanishing demographic dividend, according to Qian Wan of Bloomberg Economics. China’s working-age population—people from 15 to 59—has been shrinking since 2015, so the country needs to lift productivity. Measures that promote a better allocation of labor are one way to do that.

Hukou reform is part of a broad urbanization strategy that will foster the emergence of new megacities (those with populations greater than 10 million) in central China, Wan says. China’s urbanization rate climbed from about 20% in the 1960s to a little under 60% by the end of 2018, according to the latest available data. That’s still lower than the 66% average for all upper-middle-income economies, which is how the World Bank categorizes China, and a long way from the 81% that is the norm for high-income economies.

In theory the new policy would effectively remove barriers to receiving the hukou across much of China. Out of almost 300 prefecture-level cities, only 27 have populations exceeding 3 million, according to I-City Media, which analyzed data from the Ministry of Housing and Urban-Rural Development. The pace of change, however, will ultimately be dictated by authorities in individual municipalities, many of which either lack the resources to expand public services to support larger populations or aren’t inclined to make the necessary investments. “The central government has adopted loosening of the policy without providing financial support, so the local governments don’t have strong incentive to carry out the reform,” says Lu Jiehua, a sociology professor at Peking University and one of China’s leading demographers.

The slowest economic growth in three decades is prompting some cities to ease residency restrictions. Since September at least 30 have done so. Because the permit is often a precursor to buying a home, the moves are expected to spur sales. An index tracking shares of Chinese property developers rose 2.9% the day after the State Council statement was published.

Some Chinese cities have taken a selective approach to relaxing hukou requirements. Hangzhou, the provincial capital city of affluent Zhejiang province, and Xi’an, the capital of Shaanxi province in central China, now offer permanent residency to migrants with college degrees.

Yichang, a city of 4 million people along the Yangtze River, has gone further. In late August authorities announced that anyone able to rent an apartment would qualify for a hukou. It’s the latest in a series of attempts by Yichang’s government to arrest a population decline. Others include offering families who have a second child bonuses of as much as 2,500 yuan ($362) as well as footing hospital costs for deliveries.

In November the Guangxi Zhuang Autonomous Region in southern China removed all barriers for rural residents applying for urban residency permits while allowing them to retain rights to their farmland. If more municipalities follow Guangxi’s example, the country will make speedier progress toward the Xi administration’s stated goal of having more than 100 million rural residents relocate to cities.

The reform momentum has yet to reach China’s first-tier cities. Shanghai, Beijing, and Shenzhen are magnets for enterprising Chinese, whether young college graduates or strivers from the countryside. By some estimates more than one-third of Beijing’s residents have not been granted hukous by the city, while in Shenzhen it’s as much as two-thirds. Local officials are fearful that enfranchising them would only bring fresh waves of migrants.

In 2017, Beijing instituted a points system to determine who gets a hukou, taking into account factors such as age, level of education, and how many years one has paid taxes to the city. In 2019, 6,007 people made the cut, out of 100,000 applicants, according to data released by the Beijing Municipal Human Resources and Social Security Bureau in October. Employees of government agencies, state-owned companies, and those at high-profile private companies had the best chances of landing one of the hukous. The benefits they confer are priceless, including possible admission into one of Beijing’s most highly regarded public schools and improved odds of gaining entry into one of the country’s top universities.

The prize eluded Chen Shicai, who arrived in Beijing in 2005 at the age of 17 to attend university and stayed after graduation, finding a job and eventually a wife. In 2015 the couple decided to move to Suzhou, a city just north of Shanghai, where Chen qualified for a hukou because he had a college degree. Their daughter was also granted a residency permit. “Not having a Beijing hukou seriously affected my expectation for the future,” Chen says. “I don’t want to live in a city that doesn’t welcome me. I no longer have to worry about my kid’s education opportunities, and the whole family just feels more secure.”

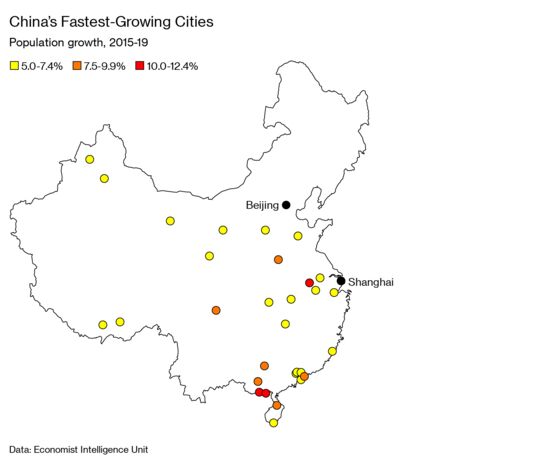

Changes to hukou laws in smaller cities—coupled with sky-high property prices and more intense competition for jobs in larger ones—are starting to reverse a decades-long migration of Chinese to boomtowns along the country’s eastern coast, according to a report by the National Health Commission in December 2018. And the country’s large migrant population started decreasing in 2016 after reaching a peak of 247 million in 2015. The populations of Beijing and Tianjin declined every year from 2015 to 2018, while the number of residents in Shanghai barely grew over the same time frame, according to a report compiled by property developer China Evergrande Group. Central and western cities including Xi’an, Chengdu, and Changsha attracted the most new residents over the period.

The trend won’t diminish inequality within China as much as redistribute it, says Wang Dan, an analyst at the Economist Intelligence Unit. “The current round of hukou reform will accelerate urbanization, especially for central and western China,” she says. “The overall inequality in China will drop with faster urbanization, but within cities inequality will increase since new migrants are mostly low-income.” —Sharon Chen and Dandan Li

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Cristina Lindblad at mlindblad1@bloomberg.net, James Mayger

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.

With assistance from Bloomberg