China Leans On Companies to Keep Employees Even If They’re Not Working

China is asking companies not to fire workers and offering incentives to keep them on the books.

(Bloomberg Businessweek) -- “We won’t slash jobs, but we can’t pay you either.”

That’s what the founders at a 200-person startup that created one of China’s most popular running apps told some of their employees in March. The statement sums up the predicament now faced by businesses across much of China, where the government is asking companies not to fire workers and offering incentives to keep them on the books.

In February revenue at the Guangzhou-based company dropped to less than 10% of its usual monthly level as government-mandated measures to contain the spread of the novel coronavirus confined runners to their homes. The founders, who asked that neither they nor the company be identified because of the sensitivity of talking about job losses, say they can no longer afford to pay all their workers yet are loath to dismiss them.

A sudden spike in unemployment that might fill the streets with disgruntled workers has been a recurrent fear for the Communist Party of China, which has outlasted its Russian counterpart by almost 30 years, in part by consistently hitting its economic growth targets.

In the late 1990s, when Premier Zhu Rongji carried out a sweeping reform of state-owned enterprises (SOEs) that resulted in an estimated 2 million job cuts, sacked workers staged protests around the country.

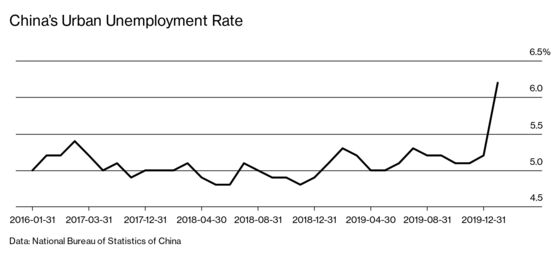

Now authorities are concerned that layoffs could further stoke popular discontent, which began bubbling up on Chinese social media platforms since evidence surfaced that government officials had suppressed early reports about the risks posed by the virus and manipulated infection statistics. A widely scrutinized measure of urban unemployment jumped to 6.2% in February, the highest since the gauge was introduced in 2018. With a record 9 million university graduates entering the workforce in 2020, the rate could rise to as high as 10% this year, says Iris Pang, chief Greater China economist at ING Bank NV in Hong Kong.

Alarm bells are ringing in Beijing. “All relevant government departments should give top priority to stabilizing employment,” said Premier Li Keqiang at a March 10 meeting of the State Council, China’s top executive body. “As long as employment is stable this year, it is no big deal for the economy to grow a little bit faster or a little bit slower.”

During previous economic shocks including the Asian financial crisis in the late 1990s and the 2008 global financial crisis, China was able to contain the rise in joblessness by ramping up investment in public works, directing banks to increase lending, and ordering state-owned enterprises to refrain from layoffs. The country also managed to weather the trade war with the U.S. last year without a marked increase in unemployment.

This time the outlook may be much worse. Lockdowns of cities, travel bans, and other measures enacted to contain the outbreak shut down a large swath of the economy for two months. Priority No. 1 now is getting businesses back on their feet. The government has cut interest rates, allowed a more lenient stance on bad loans, and sped up the approval process for companies to restart operations.

Even so, many of the nation’s private businesses say they’ve been unable to access the funding they need to meet upcoming payroll and debt payment deadlines. In a February survey of mostly small and medium-size enterprises by China Merchants Bank Co., two-thirds of the more than 20,000 respondents said they would be unable to stay in business for more than three months given their current cash reserves. Exporters, meanwhile, are seeing a plunge in orders from clients in North America, Europe, and the rest of Asia, as foreign governments step up their own public-health efforts.

Under such circumstances, most companies would quickly move to dismiss workers. Yet in places such as Heilongjiang province in the northeast, SOEs have been instructed to limit layoffs. A number of Chinese provinces are offering refunds on social security payments as an inducement not to downsize, and additional incentives may be rolled out in the months ahead.

Despite decades-long efforts to overhaul unprofitable SOEs, China’s leadership continues to rely on them as shock absorbers during times of economic strain. Workers there might have to tolerate shorter shifts, reduced pay, or unpaid leave, but they’ll keep their jobs.

Yet the ranks of SOEs have thinned considerably over the years, meaning that a larger share of the country’s workers are employed in the private sector. Private companies contribute 80% of jobs in cities, according to Vice Premier Liu He. These businesses may be less willing—or less able—to comply with the government’s request to idle workers instead of firing them, even with added incentives such as delayed payment of social security contributions.

Many Chinese university students have taken to Weibo, a Twitter-like social media platform, to vent their frustrations over their career prospects. (“Graduation equals unemployment” is one slogan making the rounds.) The government has responded by expanding the number of openings at graduate school programs and directing public agencies and SOEs to give the new grads priority in hiring. That will still leave millions jockeying for jobs in the private sector, where about a third of companies plan to cut back on hiring, according to a February survey by Zhaopin.com, a site that caters to white-collar job seekers. Only 20% of the 9,000 companies polled said their hiring plans were unchanged, while almost 37% were unsure.

The owners of the Guangzhou software startup don’t expect business to improve until September, when the competitive running season returns. The business typically hires 20 recent college graduates a year but will not be bringing any on board in 2020.

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.

With assistance from Bloomberg