Child-Care Crunch Could Trigger a Double-Dip Recession for Women

Child-Care Crunch Could Trigger a Double-Dip Recession for Women

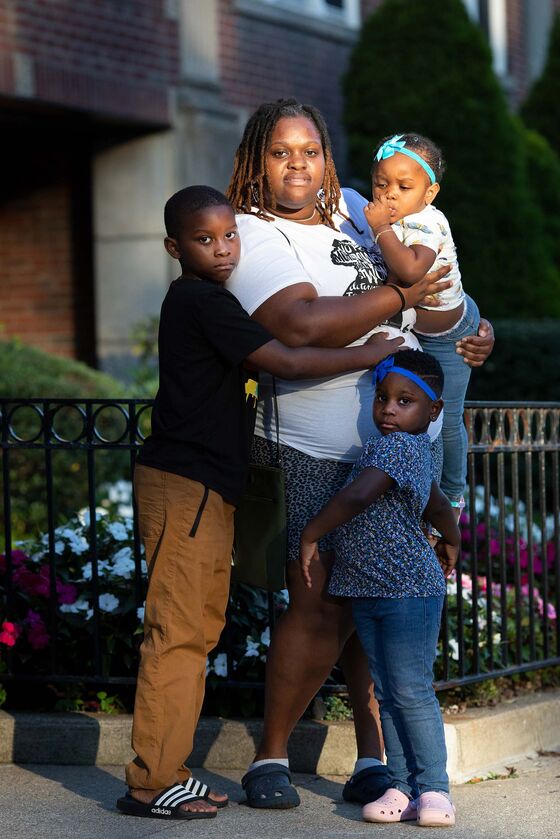

(Bloomberg Businessweek) -- Shanique Green, a single mother living in Boston, had no trouble finding a part-time customer service gig this summer to supplement her income from her regular job at a call center. Lining up the child care she needed to make it all work has been much more of a challenge.

Green, whose 8-year-old son is in primary school, used to rely on government vouchers to pay for child care for her 2- and 3-year-old daughters. But now there’s a long wait list at programs that accept them and space is tight at those that don’t. After much searching, she was able to find a nursery with room for both girls, but the $600 a week it cost would have gobbled up half the paycheck from her new job, jeopardizing her plans to build up savings to buy her first home. “It’s like a race. People have to go to work, so they’re trying to get day care as soon as possible,” says Green. “But the ones with better income take all the spots.”

Parents across the U.S. have struggled through more than 18 months of virtual schooling, suspended pre- and after-school programs, and shuttered day-care centers. As kids head back to school in person and workers back to the office, the U.S. child-care industry—which wasn’t able to meet the needs of all parents before the pandemic—can’t accommodate the sudden spike in demand. That’s left lower-income parents like Green competing for fewer seats.

“You have folks that were already on the margins, and now you have child care centers opening and closing, schools opening and closing,” says Chastity Lord, the president and chief executive of the Jeremiah Program, a nonprofit organization in Boston that serves Green and other single mothers with the aim of breaking the cycle of intergenerational poverty.

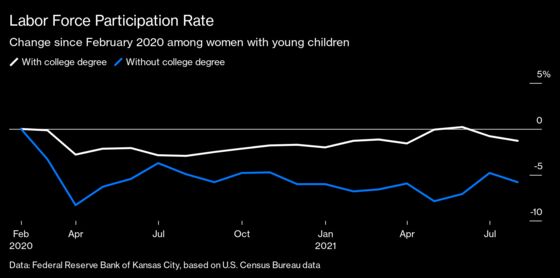

The Covid recession pushed more than 2.1 million women aged 25 to 54—those most likely to have young children at home—out of the labor force last year. About half of them have come back, but the rebound has been led by women with a college education. Participation rates for women without a diploma, especially mothers of color, lag far behind, according to an August report written by Didem Tuzemen, an economist at the Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City.

Americans without college degrees tend to work in such industries as education, health care, leisure, and hospitality—the ones most affected by the pandemic. They’re also high-contact jobs, posing an additional challenge for people who may be wary of returning to work while the delta variant drives a surge in virus cases around the country.

Almost half of all child-care centers around the country closed in the early months of the pandemic. Many have reopened only to find that they can’t return to 100% capacity because they’re unable to hire the staff they need. Some 80% of providers have reported staffing shortages and have therefore cut enrollment, according to a survey of 7,500 businesses conducted in June and July by the National Association for the Education of Young Children (NAEYC).

Weeks before the start of school, a YMCA in Maplewood, N.J., emailed parents telling them it had to cut 150 spots from its pre- and after-school programs, citing staffing shortages.

At Tiny Treasures Nanny Agency, which pairs families with caregivers in more than 10 cities across the country, New York City parents face a three-month-long wait. “In a normal year in New York, we have 100 to 120 families apply,” says founder Ruka Curate. “Now we have over 300.” Curate says more people are resorting to costlier, in-home care because they have no other options.

Vivvi, a company that provides employers with backup care options for its employees, has helped companies in New York City set up makeshift day-care centers in conference rooms, something they’re now seeing demand for across the country. “Too much of the supply doesn’t meet what parents need,” says Ben Newton, Vivvi’s co-founder and chief operating officer.

The industry’s labor crunch predates the pandemic. Pay at child-care centers has always been low, averaging $12.12 an hour, which contributes to high turnover. In a report published this month, the U.S. Department of the Treasury wrote that in 41 states more than 15% of child-care workers live below the poverty line, and almost half rely on public assistance programs for food and children’s health insurance.

More than three-quarters of providers said that low wages were the main challenge to bringing on more staff. Child-care workers “are recognizing they can make more money working just about anywhere else,” said an NAEYC report released in July, noting that many were switching to jobs in public school education, retail, or warehouses. The child-care industry employed just over 1 million workers in February 2020. After losing more than a third of its workforce during pandemic closures, it’s still down 126,700 jobs, or 12%.

Continued unpredictability in school and day-care schedules this fall may create a double dip in working parents’ labor force participation. Almost 7 in 10 parents said that they or their partner would have to quit their job if the current level of uncertainty continues into 2022. At 76%, the U.S. has the lowest rate of employment among its prime-age population compared with other wealthy, developed nations. Beyond perpetuating poverty, lower labor force participation rates also crimp a country’s growth potential and hurt its competitiveness.

“For many working people and for women in particular, child care is a prerequisite for being able to work,” Vice President Kamala Harris said Sept. 15 at an event where she called for further federal support for the industry. “If we intend to fully recover from the pandemic, if we intend to fully compete on a global scale, we must ensure the full participation of women in the workforce.”

In a pinch, Green, the single mother in Boston, could have placed her two daughters in the care of their grandmother. But Green, who has an associate’s degree in child education, says she worried the girls would miss out on the instruction and socialization that give kids a head start going into kindergarten. Then some weeks ago, out of the blue, an old professor called to see how she was getting by. Once she heard about Green’s child-care problems, she offered to foot the $600 a week tab for child care while Green waits for spots to open up at a free program for disadvantaged families.

Margot Gregory, a Pittsburgh native who had a son in November, hasn’t been as fortunate. Earlier this year, she put her name on wait lists at a few day-care centers, but when she finally heard back from one of them in April, the program’s hours didn’t work with those of the job she found managing a coffee shop. She’s now at home caring for her son while job hunting, waiting for a spot to open up at a center with a more flexible schedule. “I’m kind of terrified to get offered a great job and it not work out because of child care,” she says. —With Olivia Rockeman, Steve Matthews, and Simone Silvan

©2021 Bloomberg L.P.