The Pandemic Forces Austerity on Chicago’s Trailblazing Mayor

The Pandemic Forces Austerity on Chicago’s Trailblazing Mayor

(Bloomberg Businessweek) -- After more than two weeks of sometimes contentious hearings, on Nov. 24 the Chicago City Council narrowly passed a 2021 “pandemic budget” to close a $1.2 billion deficit. It’s a victory for first-term Mayor Lori Lightfoot. But the turbulent process revealed the difficulty of reconciling a liberal policy agenda with the economic fallout of Covid-19, even in a deep-blue city. And it’s mostly a short-term fix for the long-standing fiscal problems of Chicago, America’s third-largest city.

“This was a really hard year,” says Lightfoot, a Democrat. “Unlike anything in our city’s history.” About 65% of the budget gap resulted from losses connected to the coronavirus, as business in the tourism, convention, hotel, restaurant, and other sectors plummeted.

Lightfoot, the city’s first Black female mayor and first openly gay mayor, ran as an outsider in 2019, promising a commitment to social justice and equity as well as vowing to reform Chicago’s notorious political machine. Her $12.8 billion budget includes a $94 million property tax hike, a 3¢-per-gallon increase to the gas tax, a $30 million draw from reserves, and more funds raised from speed cameras, parking meters, and other fines and fees. The city is also refinancing and restructuring $1.7 billion in debt for a half-billion dollars in savings, a tactic referred to as “scoop and toss” that’s generally frowned upon by fiscal watchdogs.

Lightfoot secured the votes she needed for her budget by nixing her original plan to lay off 350 city workers and, instead of cutting the funding of the Chicago Police Department as some aldermen demanded, added funds for violence prevention and a pilot program that pairs police and mental-health workers on responding to 911 calls.

Critics on the council say the budget relies on regressive taxes and fees that hurt the disadvantaged. Alderman Carlos Ramirez-Rosa, a self-described democratic socialist, voted against it. “I’ve heard from so many people in my community that are just so angry that at a moment when families have less, they are being asked to pay more,” Ramirez-Rosa says. In a recent survey in his ward, 55% of respondents said they’d lost income during the pandemic, and close to a third said they struggled to pay their rent or mortgage. “Don’t give me crumbs and tell me it’s cake,” Alderman Jeanette Taylor, a progressive, said on the day of the vote, adding that food and medicine are at stake for families in her ward. “Why can’t we tax the rich?”

The enormity of the pandemic’s impact means “our options are extremely limited,” says Alderman Scott Waguespack, a Lightfoot ally who’s chairman of the city council’s finance committee. “It’s the best we could do right now.”

Covid-19 has exacerbated racial, economic, and health gaps that had long been widening in Chicago. As of Dec. 2, the city counted more than 161,000 Covid-19 cases and almost 3,500 deaths, a disproportionate number of them in Black and Latino communities. As the virus snaked through neighborhoods this summer, unrest added to the financial and emotional toll. Small corner shops along with high-end stores on the iconic Magnificent Mile were looted. The city’s costs for services—including aid to the homeless, police overtime, and small-business assistance—have risen.

Lightfoot says constructing the budget required putting the good of the whole city ahead of individual wards: “For the foreseeable future, we are in a period of reckoning with our past.” Leaders in Chicago not making tough choices and acting for short-term gain has been “long-term fiscally a disaster for our city,” Lightfoot says.

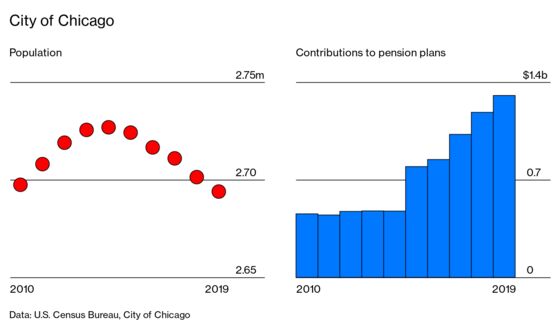

Moody’s Investors Service downgraded the city’s debt to junk in 2015 partly because of its strained pension system, which is underfunded by $31 billion. The city’s total retirement obligations for fiscal 2021 are projected to rise. (Meanwhile, its population has fallen for several years in a row, so it has fewer residents to foot its bills.) S&P, which rates Chicago three levels above junk at BBB+, lowered its outlook to negative in April because of Covid-19.

“Voters elected me because I represented change,” Lightfoot says. “I don’t think voters elected me to just kick the can down the road.” The large debt refinancing has drawn criticism as an example of just that, however, from the watchdog Civic Federation, which said it will increase debt costs in future years. City of Chicago Chief Financial Officer Jennie Huang Bennett says that the step is appropriate given the city’s challenges and that additional federal stimulus may erase the necessity for scoop and toss.

The mayor needed a simple majority of the council’s 50 aldermen to pass budget measures. Her budget ordinance got 29 yeas and 21 nays, while the property tax hike won 28 to 22. It was the tightest budget vote in Chicago since the mid-1980s, when a bloc of old-guard aldermen faced off against Mayor Harold Washington, says Dick Simpson, a political science professor at the University of Illinois at Chicago and a former city alderman. The recession caused by the pandemic left Lightfoot with “no magic way to solve the entire gap,” Simpson says. A poll conducted in late September and early October, before the budget hearings, put Lightfoot’s approval among registered voters in Chicago at 61%. If she can continue to work with the council and deliver on some progressive goals, Simpson says, lingering hard feelings from the budget process won’t necessarily dent her political appeal.

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.