A Tech Founder Cashed Out and Bet It All on Apple and Wells Fargo

Chewy Founder Invested in Only Two Stocks With No Family Office

(Bloomberg Businessweek) -- When Ryan Cohen sold the pet retailer he co-founded for $3.35 billion in 2017, he had a clear idea of what he’d do with his share of the proceeds.

He plowed virtually all of it—he declines to specify the amount—into just two stocks: Apple Inc. and Wells Fargo & Co. This is exactly the kind of thing financial advisers say never to do. Cohen, 34, is not bothered about that. “It’s too hard to find, at least for me, what I consider great ideas,” he says. “When I find things I have a lot of conviction in, I go all-in.”

He says he has no real estate, beyond the Florida home he lives in, and zero stakes in hedge funds, private equity, or venture capital funds. He has no municipal bonds—or any bonds, for that matter. He says he’s never done a private investment deal. He’s been driving the same car for years, and he’s lived in the same house since 2013.

“I try to keep my life as simple as possible, so I’m not really a family office person,” he says, referring to the private companies that the ultra-wealthy often establish to manage their investments and personal affairs. That’s bad news for wealth managers who’ve generated hefty profits selling products to the hordes of youthful, rich, tech types spawned by Silicon Valley in recent years. Those with lots money and vision but scant experience beyond the frenzy of launching their startups. The types that might be willing to let a bank shape their portfolios and investment philosophies.

If Cohen had met with a financial adviser, he or she almost certainly would’ve tried to steer him well away from his all-in allocation, toward a diversified portfolio and perhaps an index fund. “It’s down to underlying facts,” says William Bernstein, a principal at Efficient Frontier Advisors. “There’s almost no evidence of skill in security selection.” His research shows that 70% of the companies that make up the S&P 500 Index will underperform the average. Most of the average return is due to the upper quartile of performers. With a highly concentrated stock portfolio, the odds are 70 to 80% that you’ll underperform.

Then, again if you do outperform, you’ll probably do so by a wide margin, he says. In essence, it’s a throw of the dice. Which is something young entrepreneurs who’ve had early success might be more willing to embrace. “Luck is not a cure for confidence,” says Bernstein. “It exacerbates it.”

A typical investor’s savings could be decimated if they held just two companies and one took a big hit. Cohen’s wealth may give him more wiggle room, but the performance of Wells Fargo shows how much volatility he’s taken on. When he amped up his position in the bank in the second quarter of 2017, the shares were trading at an average of around $54. Cohen says his average cost basis is $46. Today, they’re worth about $32, dragged down by the sales scandal that involved employees setting up millions of fake customer accounts and later by the pandemic.

Fortunately for Cohen, the value of his Apple shares has jumped 120% over the same time period. Based on the price performance of those two stocks, the total value of his portfolio would have scarcely budged since he sold Chewy two years ago while the S&P 500 Index has risen by more than a quarter. Cohen says his portfolio, when including dividends and a few other stock holdings, has returned more than 40% over the past 3 years, beating the market. The pet retailer he sold, meanwhile, was taken public last year by the private equity firm that bought it and now has a market value of almost $20 billion.

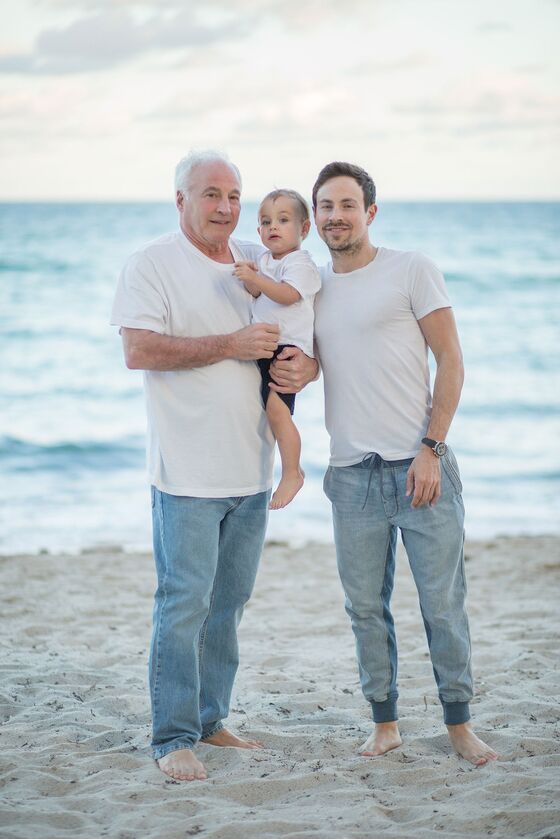

Cohen uses the word “conviction” a lot. He says it’s something he learned from his father, who ran a glassware importing business in Montreal where Cohen grew up. “He taught me how to block the noise from the masses,” says Cohen. “To have a point of view and have conviction and not waver.”

Cohen never went to college or had what he calls “a real job.” His father was his mentor and closest adviser while he was building Chewy and taught him the principles of stock analysis, which he took to heart when selecting his stocks. Back in early 2017, Cohen was getting the paperwork together to take Chewy public, while also considering offers. Then his father had a heart attack. “It put things in perspective,” he says. He shelved the initial public offering plans and sold the business. He resigned as chief executive officer of Chewy in 2018 to spend as much time as possible with his father.

His father died suddenly in December, and the past several months have been rough. Cohen says he isn’t itching to start something new. He’s doing what few high-octane entrepreneurs ever do: taking a break.

He frequently quotes the famed investor Warren Buffett, which may not be a surprise, given that Wells Fargo and Apple are major Buffett holdings. Cohen says he likes Apple because its products command intense customer loyalty, and he thinks the iPhone has become irreversibly ingrained in society. (“I’m not sure it’s fully appreciated,” he says. “We live our lives by this product.”) Defending Wells Fargo is a greater test of his self-professed contrarian leanings. It’s a smaller share of his holdings—his bet on Apple is about 60% larger in value. But he sees the bank as disciplined with its capital and likes that it’s a conservative underwriter of loans. It’s also “a bet on the U.S. economy over the long term.” He declined to comment on the bank’s 2018 sales scandal other than to say he thinks Wells Fargo will eventually emerge stronger for it.

Cohen sees both companies as consumer businesses, a type of industry he understands from building Chewy. The online retailer is famous for such over-the-top gestures as surprising customers with birthday cards or custom portraits of their pets. He likens his obsessive focus on building Chewy to his approach to stock picking. “I don’t want to swing for a single,” he says.

He wouldn’t, however, recommend his investment approach to everyone. “You need to have the temperament to block the noise,” he says. “Sometimes it feels like a roller coaster.” For most investors, a low-cost index fund is more prudent. But Cohen says he’s committed to his stock picks and has no regrets. Well, maybe one: “The execution of Amazon is just phenomenal,” he says. At Chewy, “we couldn’t have staked out a bigger competitor if we’d tried.”

Did Cohen think about buying stock? “I should have. I wish I did.”

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.