CEOs Goose Their Pay With Buybacks

CEOs Goose Their Pay With Buybacks

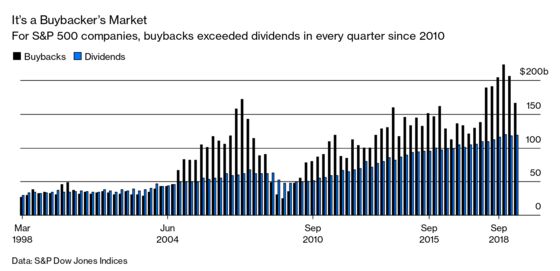

(Bloomberg Businessweek) -- Is it good or bad that U.S. corporations are buying back their own shares? It’s an important question, because buybacks have become the preferred way for companies to disgorge cash to shareholders. In 2018, S&P 500 companies bought back a record $806 billion worth of shares, a 55% leap from the year before. They’re on track to buy back about $740 billion worth this year, the second most ever, according to S&P Dow Jones Indices senior index analyst Howard Silverblatt.

There are two lines of criticism. One is that buybacks are great for shareholders but bad for workers, because they fritter away money that should be reinvested in the business or paid to employees. This is the line taken by Democratic presidential candidates Elizabeth Warren and Bernie Sanders, who support legislation that would ban open-market stock buybacks.

But you don’t have to be a liberal Democrat to question current government policy on buybacks. A second, less familiar line of criticism is that they aren’t necessarily good for shareholders. Buybacks benefit corporate executives and directors, who often take advantage of the price jump when one is announced to sell some of the shares they’ve received through grants or options. Leading the charge for this cause is Robert Jackson, a Securities and Exchange commissioner who’s been agitating for more than a year for his agency to schedule hearings on the issue.

What no one questions is that buybacks matter, a lot. Over the past two years, S&P 500 companies have plowed 58% of their operating earnings into them. When a company reduces the number of its shares outstanding in this way, it depletes its cash but boosts its earnings per share. Silverblatt calculates that S&P 500 companies have spent more on buybacks than on dividends every year since 2010. Any gain in the share price caused by a buyback goes untaxed as long as the shares aren’t sold. Dividends are taxed when issued.

The bad-for-workers camp cites research by William Lazonick, a professor at the University of Massachusetts at Lowell, who says companies such as Apple, Boeing, Cisco Systems, Merck, and Pfizer are putting workers at a disadvantage and jeopardizing their competitiveness by paying out too much to shareholders and stinting on research and development. President Trump predicted that U.S. companies would step up investment at home if they were given a tax break to bring back foreign profits, but it never happened. Companies repatriated $777 billion in 2018. The Federal Reserve in August 2019 found that the funds “have been associated with a sharp increase in share buybacks,” while the effect on investment was “not as clear-cut.”

Defenders say buybacks are a good way to get funds out of the hands of managers who might otherwise waste them on low-value or speculative investments. “It is the exhaustion of a firm’s investment opportunities that lead to buybacks, rather than buybacks causing investment cuts,” Alex Edmans, a finance professor at London Business School, wrote in a 2017 article in Harvard Business Review. There are more direct ways to raise worker pay or encourage needed investment than shutting down buybacks, these proponents say.

Fewer people have stepped forward to defend the practice of insiders selling gobs of shares to take advantage of the pop that a stock price gets when a buyback is announced. By promising to buy back shares, a company is signaling confidence in its future. To step up stock sales right after seems to some like a legal version of illegal pump-and-dump stock manipulation. “What we are seeing is that executives are using buybacks as a chance to cash out their compensation at investor expense,” the SEC’s Jackson said in a speech last year.

Jackson had his staff study 385 recent buybacks. They found that shares rose by about 2.5% more than would otherwise have been expected in the days after a buyback announcement. They found that, compared with an ordinary day, twice as many companies see executives and directors sell shares in the eight days after a buyback announcement. The value of sales goes up, too. In the days before a buyback, selling by insiders averages less than $100,000 a day. In the days after a buyback, that average climbs to more than $500,000 a day.

Jackson wants the SEC to change rules written in 1982 and revised in 2003 that give companies a safe harbor from prosecution for market manipulation if their buybacks aren’t excessive or at an above-market price. There are no limits on executives using buybacks to cash out. At a minimum, Jackson says, insider sales should be barred for a certain length of time—he doesn’t say how long—after a buyback is announced.

SEC Chairman Jay Clayton told Democratic Senator Chris Van Hollen of Maryland last December that he didn’t want to “commit to a roundtable” discussion of new buyback rules. He seemed to allude to Jackson’s request in a Nov. 14 speech when he said that “we are not in the business of dictating a company’s strategic capital allocation decisions,” including “whether to buy or sell their own stock.”

Jackson says he doesn’t want to dictate capital allocation decisions, either. If companies want to buy back their shares, he says, that’s fine. Just don’t allow executives to sell shares immediately after a buyback is announced. “I have not once heard somebody make a compelling case,” Jackson says, “that the day after the buyback is a good time for the CEO to sell stock.”

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Pat Regnier at pregnier3@bloomberg.net

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.