The Census Could Miss Millions, Even Without a Citizenship Question

The Census Could Miss Millions, Even Without a Citizenship Question

(Bloomberg Businessweek) -- Lizette Escobedo, director of the census program for the National Association of Latino Elected and Appointed Officials (Naleo) Educational Fund, oversees staff in six states. She runs a bilingual hotline. She produces brochure upon brochure. But overshadowing all her efforts is the reality that thousands of people are frightened just to answer the 2020 questionnaire. “The census has become politicized,” she says. “Many immigrant communities are scared.”

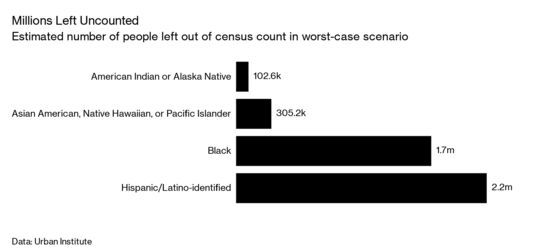

While President Trump failed in his attempt to insert a question about citizenship status into next year’s census, advocacy groups across the country say many Latinos afraid of deportation still might avoid answering. An Urban Institute study found that even without the question, an “increased climate of fear and hesitation to participate” could lead to as many as 2.2 million Latinos going uncounted. That would rob states with many Latino residents—both legal and undocumented—of federal financial support and congressional representation. “All of this distraction with the citizenship question really hindered a lot of the work that we could have been doing around hiring and census operations,” Escobedo says. “It diverted a lot of resources, and it put us behind.”

In March 2018, Commerce Secretary Wilbur Ross announced that the department planned to ask whether census respondents were U.S. citizens, setting off alarms among activists. Federal officials argued that the data would help the Department of Justice locate minority voters and thereby enforce the Voting Rights Act, but critics led by the American Civil Liberties Union filed suit, saying the question was meant to intimidate immigrants. The Supreme Court eventually found the administration’s rationale “contrived” and blocked the question.

The Census Bureau, responsible for organizing the effort every 10 years as mandated by the Constitution, relies on a patchwork network of bureau hires, local governments, and national and community groups to do the survey. “This is my fourth census, and I can tell you with all confidence, the level of engagement by partner organizations—both national and local—is at an unprecedented high,” says Tim Olson, associate director for field operations at the Census Bureau. The bureau has historically enlisted community groups to inform residents and encourage participation, especially among hard-to-count populations such as minorities, non-English speakers, and undocumented immigrants.

The data from the census determine everything from the number of representatives a state sends to Washington to funding for schools, roads, hospitals, and social assistance programs like food stamps, making an accurate count essential. This time around, the Trump administration has thrown up a daunting obstacle. Its crackdown on undocumented residents has led to raids of workplaces nationwide and deportations. Avowed racists and even domestic terrorists have echoed the president’s talk of immigrant invasions.

“There’s a large portion of my community around me that’s very scared to go to work, scared to continue doing their everyday routine,” says Esperanza Mendoza, a 19-year-old California college student offered a temporary position by the Census Bureau. “I think they’ll take extra precautions for who they open the door to.”

While census responses are legally required to be confidential and used only for statistical purposes, the bureau is part of Ross’s Department of Commerce, and he reports directly to Trump. “This is an important message at this juncture: The census is really safe,” says Olson. “ICE cannot receive any of this confidential data,” he adds, referring to the Immigration and Customs Enforcement agency, which has carried out much of the Trump administration’s campaign against undocumented immigrants. “It’s all confidential.”

The bureau has enlisted its partner organizations to help quell this fear, but for now, many are still concerned their responses could be used against them. “People don’t want to enable an agency if the agency is going to then turn around and give this information to ICE or Border Patrol,” says Antonio Arellano, interim executive director of Texas’ Jolt Initiative, a nonprofit focused on increasing civic engagement among Latinos. Beginning in March, households can fill out the survey by mail, phone, or website; advocacy groups are pushing to make clear that a census-taker is going to show up at their door if they neglect to do so. Still, many families may omit noncitizen members from their responses for fear of advertising their presence.

More than a third of Latinos lack broadband internet access at home, according to data from the Pew Research Center. Yet the availability of the internet option has the bureau scaling back on field staff; it’s planning on filling 500,000 temporary positions, down from more than 850,000 in 2010. About 1,380 Census Bureau partnership specialists had begun working in communities and with grassroots groups to educate people about the importance and security of the count as of Oct. 3. The hiring goal, about 1,500, is nearly double the number brought on in 2010. The bureau is also attempting to hire while the rate of joblessness hovers at a half-century low. Workers often need to be able to speak different languages, and all applicants must be native or naturalized citizens. Diversity among representatives is essential, but by law the bureau can’t hire based on ethnicity.

Organizations are recruiting Latino applicants for census positions in the hope that nervous families will be more willing to open the door to someone who looks like them. Gabriela Orantes, a fellow at California’s Latino Community Foundation, has worked with community organizations in Napa and Sonoma counties to organize eight hiring workshops this year. Community groups have added staff of their own: The Jolt Initiative plans to hire canvassers in the spring to spread the word. Houston in Action, a collection of organizations dedicated to broader civic participation, hired 13 community organizers. La Luz Center, in the town of Sonoma, plans to send volunteers with tablets to churches and soccer games and offer survey assistance on the spot.

Escobedo’s organization, Naleo, has a hotline with operators who can provide information on qualifications to work for the census, where to apply, and how to find out pay by location. To increase participation, it’s hired 11 regional census managers, some of whom have been on the case more than a year already. “I’m exhausted,” Escobedo says. And it’s not even 2020 yet.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Stephen Merelman at smerelman@bloomberg.net, Jillian Goodman

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.