Car-Crazy Milan Erupted Over a New Pedestrian Zone

Car-Crazy Milan Erupted Over a New Pedestrian Zone

(Bloomberg Businessweek) -- On Milan’s long list of pandemic-era public initiatives, remodeling Piazza Sicilia is a strange one to get worked up about. The city built the tiny park in just a few weeks last autumn, at an estimated cost of €20,000 ($23,600). The strip of land had been a right-turn lane at the intersection of busy Via Sardegna and four residential streets, jammed every morning with honking commuters and every afternoon with parents double-parked to pick up their kids from school. Now, with cars forced to divert around the piazza, one of Milan’s myriad traffic nightmares has become a place where children play soccer, food delivery riders perch on their bikes awaiting calls, and residents of nearby apartment blocks face off at the pingpong table.

But people are worked up. Covid-era urban planning projects like Piazza Sicilia, intended to reduce traffic and provide more public space for residents locked at home during the pandemic, have become a flashpoint. In the runup to elections scheduled for October, right-of-center parties in Milan are using such post-pandemic lifestyle changes as a wedge issue.

The alterations have been far less radical than plans such as Paris Mayor Anne Hidalgo’s “15-minute city” (which aims to redesign the metropolis so residents can get most of what they need within a quarter-hour on foot) and Barcelona’s Superblocks, where entire avenues are reconceived as open spaces. But in Milan, the automobile still rules, and Covid-era changes favoring pedestrians over cars have been more tentative. Even small programs such as the one that created Piazza Sicilia have fostered the perception among some voters that the government is waging war on the Milanese auto.

In 2015, Milan outlined an urban-planning strategy aimed at moving away from car-centric transit, and the urgent need for outdoor space that came with Covid-19 accelerated that transformation. City Hall is betting that small, inexpensive interventions such as Piazza Sicilia can turbocharge the transition without the need for grand infrastructure projects. “Covid has given us a stronger reason to say, ‘We must intervene,’ and this allowed for acceleration,” says Marco Granelli, Milan’s assessore for mobility and public works and an elected member of the local government. Granelli’s Democratic Party forms the base of Milan’s ruling center-left coalition, which took power in 2016 and was in office as Covid began savaging northern Italy. The coalition won international praise for quickly building three dozen “tactical plazas” such as Piazza Sicilia.

But that was last year. With the masks starting to come off and the urgency of the crisis easing, initiatives such as tactical plazas are no longer perceived as a simple crisis response. In 2021, the local governments in Milan and other cities have to own what they’re really doing: a fundamental redrawing of the urban landscape and a top-down social engineering experiment that seeks to steer residents away from the car, permanently. And officials need to do this while also getting reelected, because most such changes take years. If the results don’t please a majority of Milanese, Granelli’s party risks being thrown out, and his replacement would likely kill the program. Mid-August polls by Ipsos showed an opposition right-wing group just four points behind the governing coalition.

While some politicians and drivers in Milan complain that the city has rammed reforms through too quickly, 1,200 miles northeast in Helsinki there’s concern that efforts to reduce the number of autos in the center is coming too slowly. The changes stem from a desire to limit climate-warming emissions alongside a push to boost efficiency and simply make Helsinki a nicer place to live. But with traffic that’s less snarled than Milan’s, the Finns can afford to move more slowly.

The Finnish capital has set a goal of increasing the share of trips by bike from around 9% today to 20% by 2035 (in Amsterdam it’s now 36%; in London, 2%). The more incremental approach to getting there, though, hasn’t always been by choice: It wasn’t until last year that Helsinki reached its funding target for cycling infrastructure. But the city has avoided the kinds of conflicts brewing in Milan and elsewhere. A decade ago, Helsinki started to look to Copenhagen, an urban cyclist’s paradise, for ideas. As Helsinki has grown, adding 5,000 to 8,000 residents a year, so has demand for housing and transportation linking those homes to the rest of the city. “It was about integration of cycling instead of building bicycle infrastructure where there’s room,” says Oskari Kaupinmäki, a cycling coordinator for the city.

As the underfunded transformation limps along, dissatisfaction with the changes seems to be mostly about growing pains rather than a rejection of the concept. In June, after years of slow-and-steady implementation of the program, the mayor’s party won reelection, with the deputy mayor in charge of the changes placing among the most popular candidates for city council.

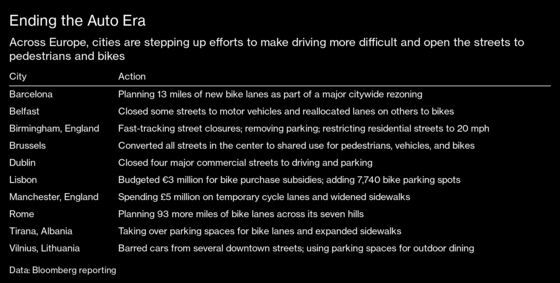

Across Europe, policymakers are questioning the free ride that cars and drivers have gotten for almost a century. From Antwerp to Zagreb, governments have launched or sped up plans to drastically scale back traffic through infrastructure upgrades, new laws, and redesigns aimed at favoring other modes of transit. They’ve wiped out parking spaces, added bike lanes, and even barred autos completely from some areas. “Cities are using the opportunity of the pandemic to accelerate things they wanted and maybe didn’t have broad consensus to do,” says Jill Warren, chief executive officer of the European Cyclists’ Federation. “Residents can be afraid of having parking spaces removed, reductions in speed limits—anything that makes driving less attractive. Taking things away from people tends to irritate them the most.”

Given a chance, though, such measures can be enormously popular. Amsterdam was a battleground in the 1970s; now the city has wide latitude to beat back the automobile and is removing 11,000 parking spaces. In June, Paris’s Hidalgo won reelection in a landslide after quickly adding 30 miles of bike lanes the previous spring. A proposal two decades ago to ban cars from the center of Pontevedra, Spain, faced strong opposition, but the mayor who implemented the plan has been reelected four times, and polls show locals have scant interest in going back.

In Milan, simple projects like Piazza Sicilia came together fast and were instantly popular, with their bright colors and minimalist designs Instagramming well. Known for style and history—and home to both Da Vinci’s The Last Supper and Maurizio Cattelan’s L.O.V.E., a 36-foot-tall sculpture of a middle finger in front of the stock exchange—Milan became a template for transforming tragedy into opportunity.

Although tactical plazas began last year as an effort to facilitate social distancing among the city’s 1.4 million pandemic-ravaged citizens, in 2021 they are more obviously a means of introducing Milanese to the Milan that could be. The strategy is to convince residents that it’s all right for Granelli to tinker with their roads and get them out of their cars, which still rule Milan’s streets (and sometimes its sidewalks). The city, after all, is where Alfa Romeo’s sexy convertibles were born. The legendary Monza racetrack is just 12 miles away. And tiremaker Pirelli operates from a skyscraper downtown.

But Milan isn’t simply a motown. Romantic wood-trimmed streetcars creak through the historic center and out into the suburbs. Italy’s largest bicycle company, Bianchi, was founded there in 1885. (Bianchi also made cars for a while, but it abandoned them in favor of bikes.) Pedestrian-friendly Navigli, with its canal-side cafes, is thronged now that restaurants are open again. Even traffic-choked Piazzale Loreto was once pedestrian, but in the 1950s, a decade after dictator Benito Mussolini’s body was hung there for everyone to spit on, it became a four-lane traffic circle, impossible to cross on foot. “Experiments help,” Granelli says. “They allow the citizen to avoid immediate change from white to black. A little culture, a little citizen involvement in saying, ‘Let’s try to do something that is not definitive’ and make them grasp the positive effects.”

Granelli’s office occupies a corner of the modern transportation department headquarters, one of the few spots in Milan that feels welcoming to people arriving by bike. Everything about the tall, square building’s entrance demands that you stride up to it, not arrive in a car or cab. Wide sidewalks mean you can’t pull right up to the front door, and one side is dominated by a long bicycle rack, where Granelli says his two-wheeler is locked up—without mentioning that the rest of the rack is mostly empty because few people in Milan commute by bike.

Granelli knows tactical urbanism’s success will define whether he still has a job in a few weeks. His opposition does, too, and it’s hitting the issue hard. “There is a big movement that is considered green, but it’s not,” says Andrea Sacchi, a candidate for city council with the right-wing Fratelli d’Italia (Brothers of Italy) party.

Sacchi, the son of a motorcycle racing official, looks like a rockabilly guitarist and writes for Italian car magazines. He notes Granelli doesn’t have an urban planning background—the transportation chief used to be a social worker—and calls tactical urbanism a misappropriation of public funds, accusing Granelli of rolling out cheap little squares to pad the city budget with Covid relief from the European Union. “It’s like greenwashing,” Sacchi says, sitting on a bench at Piazza Sicilia and gesturing dismissively at the planters filled with small trees.

Sacchi is a climate change doubter who insists auto exhaust doesn’t harm Milan’s air quality. In any other political era, he’d be just another middle-aged car guy grousing about a world moving on without him. But now he’s being recruited to write transportation policy for Milan’s chapter of Italy’s fastest-rising far-right force. Its leader, Giorgia Meloni, has surged to national prominence on the back of Trump-style provocation targeting immigrants, same-sex couples, and Italy’s left. Sacchi calls the move to make the Covid infrastructure permanent an ideological power grab by a leftist City Hall. “You have to give people the liberty to move how they want,” he says.

Looking over Piazza Sicilia, he also notes that, well, it’s actually pretty ugly. And he’s not wrong.

A year after their inauguration, many of the tactical plazas look a bit grotty. Piazza Sicilia is full of people, but it’s already falling apart under their use. The bright, surreal paint job that popped on Instagram has faded, and the picnic table wobbles unnervingly. The grass alongside Via Sardegna is patchy and uninviting, apparently unwatered. Errant shots from the pingpong tables frequently ping into traffic or pong into the darkness of a storm drain. The redesign hasn’t even reduced driving, Sacchi claims. Before, parents “came, parked, and picked up children from school. Now they still come with the car, but they park in the middle of the street.”

If the goal was just to get a foothold, the plaza clearly worked. But as Covid fades as a spur for policy, the tactical program’s hasty implementation—and even tiny design flaws affecting matters as mundane as which way a pingpong ball bounces (turning the table 90 degrees would have largely solved the problem)—have given critics an opening. “I am not against the vision,” says Geronimo La Russa, president of Milan’s Automobile Club, one of Italy’s biggest lobbies. “I am against being the Taliban. Forcing the issue is not OK with me.”

In a worrying sign for Granelli, even some members of the natural constituency for the Covid changes have voiced dismay. Cyclists aren’t wild about the 37 miles of bike lanes installed with great fanfare during the pandemic. Rather than separating bikes from cars, Milan’s lanes amount to a few stripes painted on the side of existing streets, leaving riders exposed to much of the chaotic traffic.

“They really suck,” says Iosef Tilza, manager of La Bicicletteria, a bike shop a few blocks from Piazza Sicilia. He says Milanese want to ride and estimates his shop’s sales jumped tenfold in 2020 after the Italian government spent more than €215 million on subsidies for bicycles, e-bikes, and electric scooters. But all those new bikes are still tussling with Milan’s aggressive drivers.

If Granelli faces skepticism from the likes of Tilza, he’ll have a tough time convincing the rest of Milan that the Covid emergency lanes are an important piece of the future. Even on the wide avenue in front of Tilza’s shop, the rare bike commuter is still exposed to cars racing past. Anyone not already confident on a bike wouldn’t dare wade into the afternoon traffic, and letting children pedal home from school there seems wildly irresponsible, an invitation to tragedy. “Sometimes you want to ask the designer, ‘How did you come up with this?’ ” Tilza says. “ ‘Have you ever ridden a bike?’ Boh.”

Helsinki started down its path of mobility transformation more than a decade ago, taking a full five years to study the matter with Nordic fastidiousness before even releasing a plan. The deliberate pace irritates some, but by not using Covid as a feint to rush through changes, city officials have given themselves more time to win people over.

For a mile and a half, cyclists riding downtown from the northern neighborhood of Vallila enjoy their own pathway, 8 feet wide and on a separate level from those of vehicles and pedestrians. The southern stretch takes a lane from cars, and traffic cameras enforce new, no-through-traffic regulations. Riders roll past secondhand shops, barbers, and ethnic groceries in an area transitioning from working class/immigrant to hipster. Osman Shakil, who owns a halal butcher shop beside the new cycle path, says the change has hurt business. “Fewer people are coming in because they can’t park,” he says. “There are other places with good parking where they can shop.”

Henni Ahvenlampi, executive director of Helsinki Region Cyclists, an advocacy group with 1,500 members, frequently hears complaints like Shakil’s. “The problem is there’s no continuity to the center,” she says. Indeed, a quarter-mile from Shakil’s shop, just north of a bridge that marks the unofficial border with downtown, cyclists must rejoin traffic because the lanes need to be wider to accommodate turning buses. It’s less appealing, less safe, and a disincentive for anyone seeking to commute by bike.

The city is investigating whether it can extend the path to the bridge and southward, but even if that’s feasible, work won’t be complete for three or four years. That’s both necessary and part of the plan. “Economy, design, land use codes, fire regulations—all these very solid systems are interlinked through the automobile,” says Meredith Glaser, acting director of the Urban Cycling Institute at the University of Amsterdam. “You can’t expect to uproot a century’s system overnight.”

When the city of 650,000 embarked on its mobility transformation back in 2010, “People thought of cycling as not serious transportation—like, ‘Why do we need all this infrastructure for men in their 50s who wear Lycra?’ ” says Anni Sinnemäki, a deputy mayor from the Green Party.

First, city officials conducted surveys to find out what would motivate people to cycle more. They monitored bike traffic and analyzed how and why it changed. And to increase the buy-in, they calculated the return on investment in cycling infrastructure (more than 7 to 1 in health benefits and time saved). In 2015, after four-plus years of study, the city published a biking plan, which it updated in 2019.

In the end, a methodical approach might benefit both advocates such as Ahvenlampi and doubters like Shakil in the end. Study after study has shown that cyclists actually spend more in local businesses than drivers—and that business owners overestimate the portion of customers they believe arrive in their shops by car. Along a mile of the bike path that passes Shakil’s shop, there’s not a single empty retail space, even after more than a year of social distancing restrictions.

Changes have been easier to implement in Helsinki than they might be elsewhere, Deputy Mayor Sinnemäki says, since public transit is widely used and Finland’s automobile lobby isn’t particularly strong—there’s just a single car factory in the country, employing fewer than 5,000, while Italy’s automotive industry has 250,000 workers.

Thanks to wide support for public transportation, reducing car traffic doesn’t have to mean putting everyone on a bike. The portion of trips in Helsinki on a bicycle is far lower than in Amsterdam or Copenhagen, long considered the gold standard for bikeability. But the share in private cars is also smaller than in those two cities, with public transit making up the difference. Helsinki is, after all, a place where the average temperature hovers around freezing and snow often covers the ground from December through March—though the city is trying to improve winter maintenance of bike lanes. City Hall devotes just €20 million of its €200 million in annual transportation investment to cycling. Yet the bicycle work has the support of Finland’s national government as part of its climate agenda.

Even the business lobby is on board—or at least hasn’t yet been alienated. Some doubt the willingness of Finns to frequently hop on their bikes for groceries, as Danes and Dutch do, rather than driving to the supermarket for a big shopping trip every week or so. And with a working cargo port in the central business district, the city can’t afford to choke off too much car and truck traffic, says Markku Lahtinen, director of the Helsinki Region Chamber of Commerce. “We like to support bikes, but the center must be accessible,” Lahtinen says. “All kinds of logistical chains need to be taken care of, and that possibility is diminished when cycling rules.”

If Helsinki shows the wisdom of slow, steady change, Milan offers an example of city officials facing the consequences of moving fast. As the pandemic eases, Granelli no longer has the luxury of justifying post-car urbanism as a crisis response. He has to sell Milanese on a revised model of urbanism, pushing them toward a long-term reinvention of their city.

Granelli is betting that the longer Milan’s new normal includes ideas such as Piazza Sicilia, expanded bike lanes, and fewer cars, the more people will come to support them. “It’s true that there is cultural resistance,” he says. “We have to make citizens understand the positive sides of change.”

The question is whether Covid sufficiently changed Milan, or whether opponents like Sacchi can marshal frustrations from an unfinished transition. Granelli knows that many voters will still drive to the polls rather than biking or walking. “Five years is too short to complete the vision we have,” he says. It is, however, the length of a term in City Hall. —With Alessio Perrone

©2021 Bloomberg L.P.