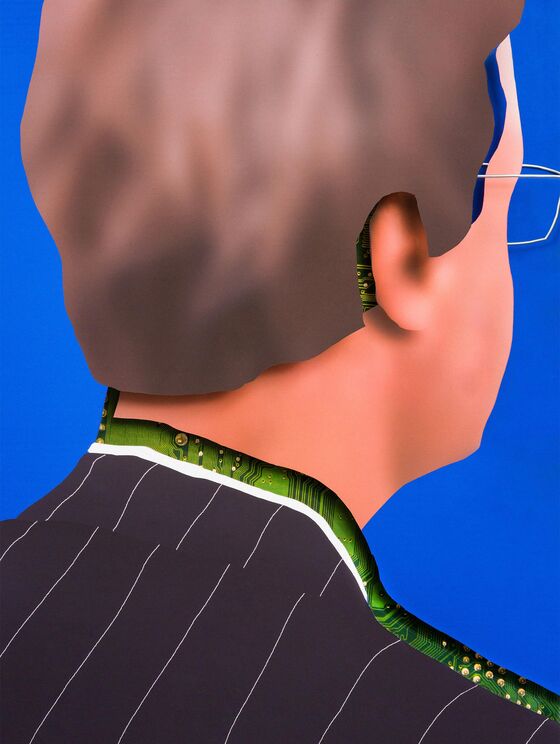

Automating the Wall Street Rainmaker

Automating the Wall Street Rainmaker

(Bloomberg Businessweek) -- Wall Street pours billions of dollars into technology every year, looking for ways to replace many of its money managers, research analysts, and traders with machines. But there’s one job that few believe can be automated—that of the investment banker. Investment bankers weave together complicated mergers and acquisitions, pitch initial public offerings to investors, and serve as confidants and counselors to chief executives. They’re also rainmakers, cultivating relationships that bring in business.

Wall Street executives have said they don’t believe their rainmakers can be replaced by algorithms because of the importance of negotiation, judgment, and relationship building. “There are still going to be people getting on airplanes, going to meet with boards and clients,” says Brian Healy, chief operating officer of Morgan Stanley’s investment bank. “That’s what we do.”

Yet it’s inevitable that much of the job would become automated, says Lawrence Katz, an economics professor at Harvard. That’s because deals require so much routine paperwork for legal and regulatory issues. Adrian Crockett, a former Credit Suisse Group AG banker who now advises finance companies on technology, estimates that automating such tasks would allow investment banks to cut head count by 30 percent. Here are some of the ways technology is changing investment bankers’ jobs.

IPOs

When LinkedIn Corp. went public in 2011, Morgan Stanley created an app—inspired by the advent of the iPad a year earlier—that made it easier to share information globally in real time with investors. In 2014, Morgan Stanley and JPMorgan Chase & Co. used an app to help keep track of investors interested in the Alibaba Group Holding Ltd. initial public offering. A year later, Goldman Sachs Group Inc. set out to reengineer the IPO business by automating routine tasks such as filling out paperwork and having compliance officers check for conflicts. In 2016 a JPMorgan executive told investors that the bank was using machine learning to better predict the best times for clients to raise money via secondary stock offerings.

Idea Generation

Aryeh Bourkoff, previously a senior banker at UBS Group AG who now runs his own investment bank, LionTree LLC, has been working with Nobel laureate and cognitive behavior scientist Daniel Kahneman to develop a process of finding deal ideas to present to clients and eventually match clients with potential buyers or sellers. The program would be a tool for bankers, not a replacement for them.

Activism

Goldman Sachs this year unveiled an activism defense app that’s the product of a two-year project. By sifting through historical data, the bank gives clients a proprietary score on how vulnerable they are to raiders and a sense of how their investors view them relative to rivals. The data let investment bankers create presentations in a fraction of the time and allow customers to explore the bank’s data on their own. Separately, Lazard Ltd. has been scouring data to learn how large shareholders behave in corporate struggles. Morgan Stanley has also been using analytics to help bankers advise clients on their vulnerabilities.

Predictive Analytics

Investment banks including Harris Williams & Co. and William Blair & Co. that work with so-called middle-market companies are sometimes enlisted to help their clients find a buyer. They’ve been collecting data on thousands of private equity firms and other potential buyers and are trying to find ways to use predictive analytics to identify likely bidders. They also crunch data such as buyers’ histories to see how effective they are at closing deals. BankerBay Technologies Pte. describes itself as “the world’s first deal origination platform to use a complex algorithmic approach” to match buyers and sellers of midsize companies. BankerBay Chief Executive Officer Romesh Jayawickrama says large banks have begun to hire his firm because it automates tasks that would otherwise take large teams of bankers to perform, making smaller transactions uneconomical. “We help facilitate a process that would have taken 100 bankers to do,” he says.

Deal Databases

To help private equity firms identify suitable targets, UBS screens thousands of publicly traded companies to find ones that aren’t in highly cyclical businesses and have stable cash flows and relatively low valuations. The bank applies “what if” scenarios to see how a target’s cash flows would be affected if the company took on a lot of debt, as typically occurs in buyouts. What used to take junior bankers days and weeks to compile can now be quickly run through algorithms and code.

In a similar effort, Goldman Sachs has built a data set of every deal valued at $1 billion or more dating to 2008, compiling a wide range of metrics such as leverage, how a stock price may react if bankers change the mix of stock-and-cash acquisition offers, and synergies, which are the cost savings or increased revenue a client says a deal could create. Ultimately, the findings help CEOs present takeover ideas to their boards with greater confidence and also allow them to more clearly communicate the rationale for a major takeover to investors.

JPMorgan has a similar database of all of its deals and has also built a “corporate finance dashboard” so its clients have access to some of the bank’s data on demand.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Eric Gelman at egelman3@bloomberg.net

©2018 Bloomberg L.P.