Disco-Dancing German’s Secret Lab Could Disrupt Diamond Industry

Disco-Dancing German’s Secret Lab Could Disrupt Diamond Industry

(Bloomberg Businessweek) -- The band at the 43rd annual International Precious Metals Institute Conference is billed, at least according to the huge glowing sign near the stage, as Abbacadabra, “the ultimate ABBA tribute.” But talented as they are, Ingo Wolf, a 54-year-old German scientist and serial entrepreneur, sees room for improvement. “It’s very difficult to make a copy,” Wolf shouts over a rendition of Money, Money, Money. He wears a hotel-branded polo shirt, a guitar pendant necklace, and a chocolate smudge on his lip from the nearby fondue fountain (sponsored by Pamp, the Swiss seller of gold bars). “Everyone expects you to be as good as the original.”

As we sip Heinekens at a booth at the Peppermill Resort’s Edge Nightclub in Reno, Nev., Wolf and I discuss how the singers’ glittering microphones look almost as if they’re made of osmium, the precious metal he’s come to this trade show to promote. Of course, if they were made of osmium, they’d be worth more than all of ABBA’s music royalties combined. “You have to mine 10,000 tons of platinum ore just to find a sugar cube of osmium,” he asserts. “This is what we call rare.”

Wolf’s big bet is that the element, which is extracted in vanishingly small quantities as a byproduct of nickel and platinum mining, has commercial potential even greater than that of diamonds. Osmium crystals, which, unlike diamonds, can form only in laboratory settings, have stronger abrasion resistance and purportedly refract light at greater distances than the traditional engagement ring gemstone. Since starting the Osmium-Institute, a sort of for-profit advocacy group that oversees trade certifications and outreach to merchants and consumers, Wolf has been talking up these and other distinctive properties, such as osmium’s highest-of-all-metals density and its gorgeous, Atlantis-blue finish.

Osmium also happens to be a potential chemical weapon: In its oxidized state, the element, discovered in 1804 and named after the Greek word for “odor,” is extremely toxic. It can cause lung damage—researchers describe it as “dryland-drowning”—and eye damage so severe it stains corneas black. Wolf once risked a nonlethal sniff of toxic osmium tetroxide, which, he says, smelled of “garlic and onions, like a doner kebab.” He and his lab partner claim to have developed a crystallization process that renders osmium harmless and transforms it into the “chameleon of jewelry,” as one of the institute’s many informational websites phrases it. These mirrored gems can then be cut into diamondlike star pendants that sell for $5,800 or can be sold to investors as $1.3 million discs.

Wolf guards his proprietary method so closely that he implores me not to disclose his chemist partner’s name or their lab’s location in Switzerland. “As you American guys say, ‘This is TOP SECRET!’ ” he says in theatrical, umlaut-laden English. “The best protection is if gangsters don’t know where to go.” For that reason, he doesn’t store any osmium on-site at the institute. “If they run in with Kalashnikovs, they could only steal some files,” he says. “There’s so much money involved that it’s really dangerous. This is not a joke.”

Maybe not, but there’s something slightly comical about Wolf, who sports silver stubble, a mess of white hair, and an ever-revolving selection of golf shirts, and says he bathes only by waterskiing. He tells me that, in addition to osmium, he’s been involved in 14 ventures, including an internet-based television company, a 24/7 dance studio, an electric car project, an infrared-paint home-heating startup, and a rockabilly trio called the RaceCats, for which he remains lead singer and guitarist. His 24-year-old vice director for international business development, Scarlett Clauss, a former model who business associates often mistake for Wolf’s girlfriend, jokingly calls him a Rampensau, which she translates as a “pig that likes the spotlight.”

In the boom-and-bust game of precious metals, such charismatic yet slippery qualities may be exactly what’s needed to alchemize a whole new human obsession, fashioning extravagant value and elemental infatuation from nothing more than very, very dense primordial dust. Wolf estimates there’s $50 billion worth of accessible osmium left in the Earth’s crust, a value he predicts will quadruple in the next five years. Of course, the market could crash just as easily. It all depends on whether he can convince industry players, such as those at this Reno nightclub, that osmium diamonds are even better than the original. The only difference between his wizardry and Abbacadabra’s? “They’re doing pop!” Wolf yells over the music. “We’re doing rock ’n’ roll!”

The following day, Wolf, introduced as “Mr. Osmium,” delivers a talk at the Peppermill titled “Will Osmium Be Girls’ New Friend?” The crux of his pitch is that diamonds are overvalued as gemstones, at least relative to what he’s selling. Diamonds, he says, are neither particularly scarce—geologists estimate there are trillions of tons buried beneath the Earth’s surface—nor unique, given the rise of synthetics, which are “grown” in labs and dramatically cheaper than their natural counterparts. “Man-made diamonds will crush this market completely,” he tells the audience. Diamond goliath De Beers, he projects, could be bankrupt in as little as two years. (“Global demand for diamond jewelry is at an all-time high,” De Beers Group spokesman David Johnson responds. “Millennials have become the largest purchasers of diamonds around the world.”)

Mr. Osmium grew up a chemistry nerd and later studied theoretical physics at Munich’s top-ranked Technische Universität. But he also loved rock music and dancing “boogie-woogie” at the city’s discos. (He says these more artistic pursuits were a way to break free of his periodic table and flirt with “ladies,” a word he uses frequently.) He dropped out of college to build a record company and, in the late 1990s, started an online video conglomerate, Grid-TV. By December 2006, he had a staff of 110 and 230 web TV channels. Wolf boasted to Die Zeit that Grid-TV would soon reach 45,000 stations and expand around the world—and then to Mars. It was pure bluster: A month earlier, Google had acquired YouTube. The site “crushed us down fast,” Wolf recalls. “It was brutal.”

As part of his Grid-TV gig, he ran a few channels devoted to technical and scientific topics, such as commodities. Intrigued, Wolf began trading himself. In 2011 a friend gave him a tip about gold deposits in Bulgaria. Wolf flew to the country to file land claims. “It was still like the Wild West there,” he says. “Standing in the dirt, trying to build streets in areas where this is not possible, and making holes in the ground: This is gold business.”

The effort was a bust, but it gave him a thirst for untapped treasure. “With mining, it’s always, ‘There are billions in the ground! We’re going to get so rich tomorrow!’ ” he says. Then, at a Munich commodities conference in 2013, he bumped into the secret future laboratory collaborator, who was searching for a partner to commercialize his idea of crystallizing osmium. He says they signed an exclusive contract, and their osmium business was born in 2014.

As he attempted to build a new commodity from scratch, Wolf cultivated investors, precious-metal miners, gemstone wholesalers, and high-end jewelry designers to try to determine what forms of osmium would prove most seductive to the market. He wanted to imbue the company with a younger ethos than is typical in the world of precious metals and hired fresh faces such as Clauss, whom he met in line at a grocery store while buying sweets. (“We are not looking for beautiful ladies—we are looking for competence and open minds,” Wolf says. “What came out was a bunch of young beautiful ladies who are able to work hard.”) He also took cues from Silicon Valley, designing the institute’s minimalist packaging in the style of Apple’s and basing its business model on Amazon.com’s. “We really want the wholesalers to make the money,” he explains. “We just want to be a fulfillment company—a very, very small Amazon for osmium.”

Prior to signing their deal, Wolf’s lab partner teamed with Hublot SA for a $172,000 osmium wristwatch. “Hublot was obviously too early,” says Mathias Buttet, the Swiss watchmaker’s director of manufacturing research and development. “This kind of product requires a huge marketing investment, because no one knows this metal.” (When asked about the possible toxicity of osmium, Buttet says its osmium crystals are safe, though he acknowledges the company didn’t test for toxic emissions, jokingly adding, “All our researchers became strange, and it is probably for this reason that our future collections are even more crazy.”) Eventually the Osmium-Institute began promoting CD-size osmium plates, designed to be stored in vaults as a long-term investments, at $138,000 a pop. Each disc is tagged with an identification code, which the institute tracks in a database to prevent forgeries and trade manipulation.

For these efforts, Wolf expects to take a 3% to 7% cut of whatever osmium flows through the institute and its partner lab. In his assessment, there’s only 9 cubic meters of osmium left in the Earth, merely 2 of which can be mined. When these resources are depleted, he imagines prices will skyrocket. “It’s a natural and economic monopoly,” he says, adding that there are no rival commercial applications for the element beyond jewelry except for some tiny quantities used in microscopy and medical treatments, fountain pen tips, and compass needles. With its ultra-hardness, osmium could yield advantages as an alloy for submarines and spaceships, but, as Clauss says, “there’s probably only enough osmium to build half a submarine, and it would cost $44 billion.”

After his sales pitch at the jewelry seminar, Wolf rushes back to his hotel exhibit booth. There he’s set up two tables covered with brochures, golf tees with www.osmium.info printed on them, and tens of thousands of dollars’ of jewelry samples. There’s also a screen displaying pictures of women in low-cut shirts, their décolletage adorned in osmium diamonds. (“I’m surprised you even looked at [the osmium],” Clauss teases.) Wolf is in great spirits after his presentation. He sprints to retrieve miniature bottles of Jack Daniel’s (sponsored by Mastermelt America LLC, an alloy recycler in Tennessee) and resumes his Rampensau-ing, with me as his audience of one. He suggests I ditch my job as a reporter and become a U.S. osmium reseller. He invites me to his villa near the Alps. Before swigging another shot of whiskey, he toasts to the future of osmium: “Prost!” he says. It’s 11:41 a.m.

We meet again later that day at a pool party (sponsored by Loomis AB, the armored-truck cash-handling company), held on a terrace cordoned off with velvet ropes to keep the conference throngs away from the resort’s splashing guests. Wolf arrives in swim trunks, a Mercedes‑Benz After Work Golf Cup polo, and Armani glasses. He swipes a piña colada delivered by a waitress in a bikini and, as a Beach Boys song floats over the patio tables and lounge chairs, gets down to business.

Wolf isn’t here just to party and hit the links, though he did take second place at the precious-metals golf tourney. Yesterday, in fact, he encountered a Russian mining source who boasted that he had at least several hundred kilos of raw osmium to sell. (“A hell of a lot,” Wolf beamed to me earlier that morning. “This could be $500 million in terms of revenue.”) At the pool he allows me to watch from a distance as he privately negotiates a deal with the Russian before signaling for me to come over. Wearing a dark suit, the metals dealer agrees to discuss his stockpiled osmium. But when I ask for his name, he tells me in a Russian accent that I’m not authorized to reference it in my article.

“Otherwise you will one day breathe the long breath of osmium,” Wolf says, grinning.

“Yes, you will find yourself in a mine somewhere,” the Russian adds, chuckling.

“A closed-up mine!” Wolf agrees.

As usual, I don’t know what to make of the osmium peddlers’ pronouncements. Neither, it seems, does anyone else in Reno. In an adjacent hot tub, Brian Ledgerwood, a longtime specialist of commodity policy at the U.S. Department of Commerce, tells me he’d never even heard of osmium prior to Wolf’s pitch. Jenny Luker, president of Platinum Guild International USA, a leading trade association, saw Wolf’s conference talk, too. But she informs me that she simply cannot speak to osmium’s value, even though it’s a platinum-group metal.

When I later ask Munir Humayun, a geochemistry professor at Florida State University who studies osmium, about Wolf’s assertions, he tells me by email he’s not aware of the specific numbers Wolf often cites regarding the element’s mining yields and scarcity—“rhodium is rarer,” he says—and that he doubts the institute’s claims that it can be rendered nontoxic. “I wouldn’t want it laying around the house. There is no way to completely eliminate osmium’s toxicity,” Humayun says. “I’m not aware of anyone being that interested in osmium that they could pull a De Beers on the osmium market.” (Wolf says the crystals are chemically inert and would only be dangerous if oxidized again; with osmium’s high melting point—5,491F—this is unlikely to occur in everyday life. Clauss adds that the institute has done studies determining that no toxic osmium tetroxide was found below 752F.)

Of their osmium data sources, Clauss says they are “compilations of estimates that we’ve obtained from partners over the last few years. And it’s backed up with sources on the net and also from Hublot.” (The watchmaker is unclear about the provenance of its data, which Hublot’s Buttet says comes from an unspecified group of geologists. “It is obvious that Hublot does not have to carry out these analyses,” he says. “If geologists tell us that osmium is the rarest metal, Hublot cannot contradict that.”)

On the other hand, Mark Hanna, chief marketing officer of Richline Group, Berkshire Hathaway Inc.’s precious-metals subsidiary, is charmed enough by Wolf’s novel presentation to order his procurement team to evaluate osmium’s potential. “It has to have a certain level of style, sparkle, and emotional value,” he says. “You can’t just put rocks into [jewelry] and say, ‘Look how cool this is.’ You need to develop a credible, emotional marketing story. The material on its own is not the story. The story of the material is the story.” And as Hanna joked to Wolf following his performance onstage, he deserves a show on QVC.

Wolf realizes he’ll face skepticism as this journey continues. It’s especially complicated given that he appears to have his fingers on so many facets of the market, including osmium’s mysterious crystallization process and practice of self-certification, and his loose connections to Oicoin, an osmium-based blockchain token that completed its initial coin offering in July. The daily price chart for crystallized osmium, which depicts values soaring 630% to $1,300 per gram in the past six years, is calculated on a Microsoft Excel spreadsheet that the institute maintains and then uploads to a website, which also features videos of Wolf pitching the element’s upside.

But Wolf, who tells me he’s had to wear countless “costumes” in his career to succeed, all but guarantees an osmium boom. Revenue is up 150% in the first quarter of 2019, he says, and the institute is readying a global marketing campaign. Although it’s taken five years to attract 130 reseller partners, by the end of next year, he assures me, they’ll have “10,000 people around the planet selling osmium.” As for those “young beautiful ladies” he consistently recruits for the institute? He swears that whatever sex appeal they bring to these precious-metals conferences is serendipitous.

“It’s not intentional,” Wolf vows to me near the pool, after finishing off a vanilla ice cream cone. “I know people talk about that! Of course I do! I am a TV guy—never forget that!”

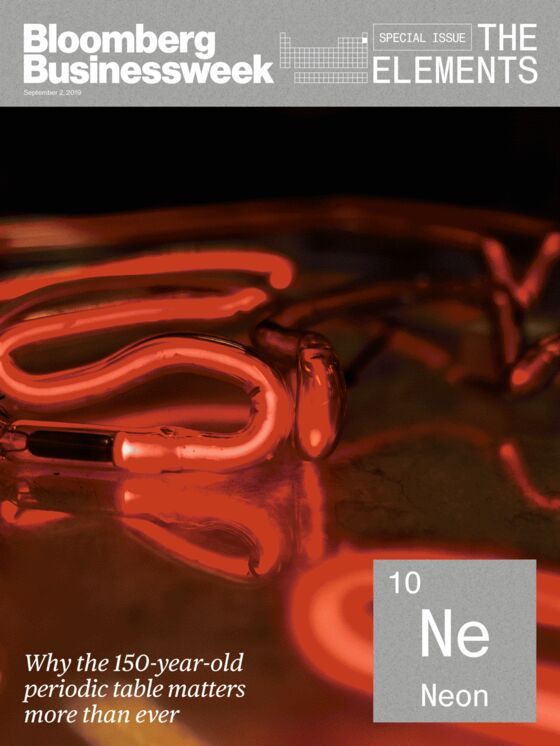

This story is from Bloomberg Businessweek’s special issue The Elements.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Jim Aley at jaley@bloomberg.net, Max Chafkin

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.