Can This Finance Star Pull Brazil’s Economy Out of the Dumps?

Brazil’s fate lies in the hands of one who knows little about politics,and a president who knows little about economics.

(Bloomberg Businessweek) -- It’s been some 40 years since a small group of Milton Friedman disciples returned from the University of Chicago to their native Chile and, under the watchful eye of the repressive dictator Augusto Pinochet, unleashed a wave of free-market reforms that turned their country into the economic envy of Latin America. Friedman beamed with pride as Chile posted one spectacular economic growth figure after another—7 and 9 and 11 percent. He called it the “Miracle of Chile.” His protégés quickly became known as the Chicago Boys.

Taking all this in was another young Friedman pupil—a Brazilian by the name of Paulo Guedes. Fascinated by the transformation, Guedes moved to Santiago, and while he didn’t stay long—Pinochet’s henchmen put a scare into him one day—the lessons stuck with him. In an interview with Bloomberg News in March, he said Brazil “should’ve done what the Chicago Boys instructed.”

Now Guedes, 69, gray-haired, and brimming with self-confidence, will get his chance to do just that in the incoming administration of the far-right nationalist Jair Bolsonaro. With the newly minted title of economy minister, Guedes will likely assume the powers of the ministers of finance, planning, and industry. The Brazilian press has dubbed him the superminister.

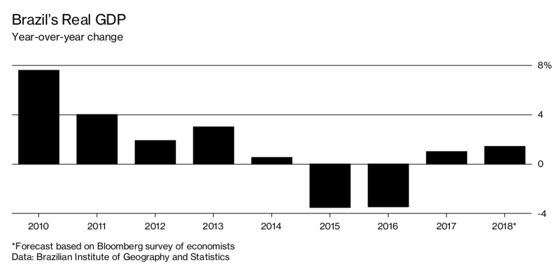

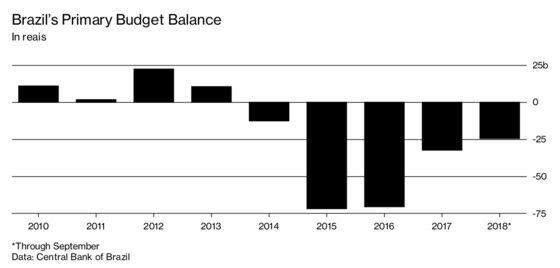

There’s a lot of pressure to produce results—and fast. The country has been in an economic funk for the better part of a decade, the result of heavy-handed government meddling in private industry, a sprawling pay-for-play corruption scandal, and political gridlock that allowed the budget deficit to balloon. It feels like forever ago when Brazil was the highflying B in the BRICs, racking up record earnings on commodity exports and, in a sign that it had arrived on the international stage, pledging billions of dollars to help countries struggling in the aftermath of the financial crisis. Its sudden reversal of fortune presaged the broader downturn in Latin America and, to a certain extent, in emerging markets as a whole.

Guedes has said his priorities are to sell off dozens of state companies, rein in the pension-system deficit, deregulate industries, and cut taxes to attract investment and create jobs. The question is whether his new boss and the divided and unpredictable Congress will let him.

Bolsonaro is a tricky read. The former army captain has strong views on homosexuals (they should make no public displays of affection) and on how to combat soaring crime (shoot first, ask questions later) but seemingly few on the economy. He has openly admitted he’s mostly ignorant on the subject; when he has offered up an idea or two of his own—such as banning Chinese companies from investing in Brazil—it’s often been to stake out some unorthodox position laced with elements of populism.

True, Bolsonaro has said on multiple occasions that he agrees with Guedes’s agenda, but it’s hard to know how much he really means it. Monica de Bolle, for one, is dubious. His appointment was “just an opportunistic way to signal to gullible markets and other private-sector people that we’re going to fix the economy,” says the professor at Johns Hopkins University’s school for international studies. Bolsonaro needed their backing during the campaign, de Bolle says, but “when push comes to shove, it’s not going to happen.”

Brazilian markets did rally relentlessly in the runup to Bolsonaro’s victory. And perhaps that was a show of gullibility on the part of traders and bankers, but they’ll tell you that, if nothing else, Bolsonaro’s victory last month prevented the dreaded Workers’ Party from returning to power. They’re still furious at the leftists for driving the economy into the ground. And yes, they’re inclined to believe that Bolsonaro will stick to Guedes’s economic formula.

Why? Well, Guedes must have secured some private assurances from the president-elect; otherwise he’d never have risked his hard-earned reputation by joining the campaign. This is a refrain heard time and again, in one form or another, in the hallways of São Paulo banks and on the leafy street corners of its financial district.

OK, but if not? What if Guedes is quickly forced out? One São Paulo analyst cringed at the thought. The Bovespa index would tumble to 50,000, he blurted out in an interview. It was hovering around 88,000 that day. That’s almost certainly an overstatement, but the exchange does underscore how much is riding on the man. “Guedes is the guarantor of Bolsonaro’s alleged conversion to liberalism, and if for any reason he leaves the government, there will be an earthquake in markets,” says Ricardo Lacerda, chief executive officer of São Paulo-based boutique investment bank BR Partners.

He worked closely with Guedes when the pair jointly managed a proprietary investment fund a few years ago. Lacerda calls him a “brilliant economist”—a widely shared view in Brazil. Since beating his hasty retreat from Pinochet’s Chile four decades ago, Guedes has grown into a towering figure in Brazilian financial circles, especially in his hometown of Rio de Janeiro. Over the course of a 35-year career, Guedes founded, alone or with others, a private equity firm, an asset-management company, and, most notably, Banco Pactual, an investment bank. He also started a think tank, Instituto Millenium, to promote free and efficient markets across Latin America, and a private business school in Rio.

At various times, Guedes taught math and economics at two of the city’s top universities. One of his students was Arminio Fraga, who went on to manage money for hedge fund titan George Soros and then, as head of Brazil’s central bank, helped pull the country back from the edge of financial collapse in early 2001. Fraga speaks highly of his old professor and the Friedman-inspired free-market capitalism theories he brought into the classroom. They offered a much-needed counterbalance, he says, to the Keynesian teachings that were in vogue during his college years.

But as Fraga observes Guedes in action today, what jumps out at him is the lack of specificity in his reform proposals. The administration will take office on Jan. 1; it will have a very short honeymoon period to get things done. “There are few details in practically all areas,” says Fraga, who plans to hand Guedes a proposal he drafted to whittle down the massive deficit in the pension system.

This lament touches on yet another key concern: Guedes, for all his accomplishments, will be out of his element in Brasília, the capital. The country’s fate lies in the hands of a superminister who knows little about how politics works and a president who knows little about how economics works. If they somehow manage to pull it off and Brazil enters an era of robust growth, shrines to the two men—the Chicago Boy and the paratrooper turned president—will be built across the country. If they fail and the country sinks deeper into economic and political mayhem, that 50,000 Bovespa prediction might not look so crazy after all.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Cristina Lindblad at mlindblad1@bloomberg.net

©2018 Bloomberg L.P.