Congratulations on Winning Sears Bid, Eddie Lampert. Now What?

And the Chance to Save Sears Again Goes to … Eddie Lampert!

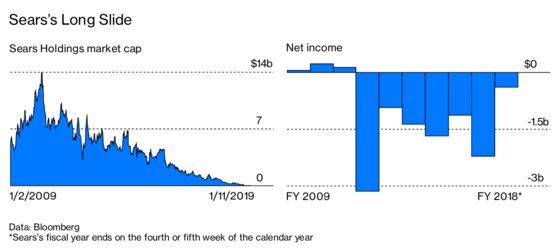

(Bloomberg Businessweek) -- More than 100 years ago, retailer Sears, Roebuck & Co. leveraged what was then the latest technology—the U.S. postal system—to become the Amazon.com of the 20th century. Its catalog and mail-order business revolutionized American shopping, and as recently as 30 years ago, the sales of Sears topped those of Walmart Inc. Since then the advance of discounters, specialty retailers, and online sellers, along with plenty of self-inflicted wounds, has sent Sears Holdings Corp. plodding toward extinction, going from about 3,900 stores at the end of 2009 to 766 at the time of its bankruptcy last year. Today, Walmart is America’s No. 1 retailer, and in recent years key pieces of once-dominant Sears have slowly been sold off.

That grim history didn’t keep billionaire hedge fund manager Eddie Lampert, Sears’s current chairman and former chief executive officer, from swooping in on Jan. 16 with a last-ditch plan to buy the company’s assets during a bankruptcy auction, days after Sears and its advisers rejected his earlier offer. On Thursday, Sears announced that Lampert’s $5.2 billion bid had prevailed.

Allies say Lampert saved an American icon and the jobs of its almost 50,000 workers. Others say he simply delayed its inevitable death. Still others say he had a compelling personal motive to stay involved after creditors threatened legal actions over Sears’s asset sales during the years he led it.

Besides having to offer more than $150 million over his earlier bid, Lampert had to give up a key bargaining chip to win the bidding. He’d been asking unsecured creditors to indemnify him from possible legal action over what the creditors allege were conflicts of interest in the stripping of assets from a failing company. Lampert has said the deals were properly crafted and kept the chain alive. Sears declined to comment. ESL Investments Inc., Lampert’s fund, didn’t immediately respond to requests for comment.

Lampert is “not a regular buyer,” Eric Snyder, chairman of the bankruptcy practice at Wilk Auslander, which represents some Sears landlords, says. That’s because the retailer owes its chairman and his fund more than $1 billion.

Whatever the deal does to eliminate some of Lampert’s legal liabilities, it does little to improve Sears’s prospects. The chairman crafted the winning bid by converting into equity some of the money owed him by the retailer. Yet the U.S. consumer landscape hasn’t changed much since October, when the company filed for Chapter 11 protection with liabilities of about $11 billion. Millennial shoppers continue to favor clicking on retail websites over heading to the Sears store at their local mall. And Amazon is still eating the metaphorical breakfast, lunch, and dinner of many retailers. “Is this big-box chain a viable business?” asks David Wander, a bankruptcy attorney at Davidoff Hutcher & Citron who represents two Sears vendors, echoing the skepticism of many creditors. “If Mr. Lampert is successful in restructuring the company with a deleveraged balance sheet and the supposed profitable stores, will it make money in this challenged environment where everyone’s getting hammered by Amazon?”

Middle-market department-store chains haven’t had a good decade. Macy’s Inc. and Kohl’s Corp. recently reported disappointing sales even as Americans spent like crazy this holiday season. But plenty of Sears’s wounds were self-inflicted. The retailer did pump money into expanding its online capabilities and sublet some of its overly large mall stores. Yet store upkeep languished under Lampert, with the company spending significantly less than its peers on keeping its outlets spiffy and well-staffed—something consumers increasingly expect from brick-and-mortar merchants.

“As T.J.Maxx and Target have shown, there are still opportunities to grow underlying sales with strong in-store value offerings,” says Deborah Weinswig, founder and CEO of Coresight Research, a global retail think tank. Not so at Sears. From 2011 to 2016, Sears’s sales densities, the revenue generated by a given area of sales space, fell 25 percent, more than any other major retailer, she says.

The company’s stretched finances also became an ever-greater handicap as management repeatedly borrowed to fund operations and multiple turnaround attempts. “You can’t load debt on a business that’s shrinking,” says Greg Portell, lead partner in consulting firm A.T. Kearney’s consumer and retail practice.

But that’s exactly what Sears did. From the time Lampert took over as CEO, after a staggering $3.1 billion annual loss in 2012, until the October bankruptcy filing, total debt soared while revenue plunged. Same-store sales, a key metric that tracks changes in annual sales at stores open at least 12 months, have dropped every year since the 2005 merger of Sears and Kmart—despite the closing of many underperforming locations.

Lampert promoted that retail match-up as one that could compete with Walmart, but the sibling chains suffered from unsuccessful ideas and shifting strategies, such as the ultimately scrapped plan to put grocery sections called Sears Essentials into hundreds of Kmart outlets.

That left creditors to watch as the company burned through cash that many now argue could have been used to pay off debt in a liquidation. Others are miffed that Lampert or ESL Investments were related parties in some transactions involving assets pulled out of Sears over the years.

When Sears spun off Lands’ End in 2014, Lampert became the biggest shareholder. He and his affiliates now own two-thirds of the lagging but still-profitable apparel company. In 2015, Sears sold Sears and Kmart brand stores worth $2.7 billion to Seritage Growth Properties, a real estate investment trust. Lampert and ESL Investments owned about 2.7 percent of the REIT’s shares on Sept. 30. “Mr. Lampert, he giveth and he taketh away,” says Wander, the bankruptcy attorney. “He says, ‘Here’s a dollar in cash,’ and he takes $1.10 in assets.”

One of the few options remaining for creditors would be to challenge the bankruptcy auction results in court. Such a move would come with political risks, because the alternative would probably be a liquidation of Sears that would put thousands of people out of work. Job losses in a bankruptcy are often an afterthought for negotiators trying to squeeze as much money as they can out of a dying enterprise. But times could be changing. Last year former employees of Toys “R” Us Inc. protested their mass firing after the retailer’s liquidation, attracting the support of Democratic presidential hopefuls Elizabeth Warren and Cory Booker. The toy seller’s private equity sponsors ended up creating a $20 million hardship fund for the more than 30,000 workers.

Now Wall Street is increasingly conscious of contributing to a decision to liquidate. “For many lenders, it’s not just about narrowly mitigating losses on a particular investment,” says Steve Wilamowsky, a bankruptcy and restructuring partner at Chapman & Cutler. “There are reputational and institutional concerns at play that in the long run are probably more important than an extra few cents on the dollar on any one loan.”

To contact the editor responsible for this story: James Ellis at jellis27@bloomberg.net, Bob Ivry

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.