Can Britain Measure Up Without the EU?

Can Britain Measure Up Without the EU?

(Bloomberg Businessweek) -- Its imperial heyday is long over, but the legacy of Britain’s global trading network endures. The Sydney Harbour Bridge, the bollards of the Puerto Madero waterfront in Buenos Aires, India’s arterial railway network, and other key pieces of international infrastructure were all designed, engineered, or manufactured by the United Kingdom.

The residual national memory of that era was a powerful motivational tool for those who advocated for the Leave side in 2016’s Brexit referendum. Ditch the collective sovereignty of the European Union, they argued, and you’d reestablish Britain’s special place in the world economy.

But the champions of what’s become a frantic effort to sever the U.K. from the EU have laid bare the paradox at the heart of Brexit. Whatever shape the separation agreement takes, the country that mastered globalization in the 18th and 19th centuries has succumbed to the popular suspicion of it in the 21st. Die-hards may be right, and Britain may well be headed for a bright future. But its immediate one will be defined by isolation and economic self-harm as Brexit caters to the previously un-British notions of protectionism and nativism.

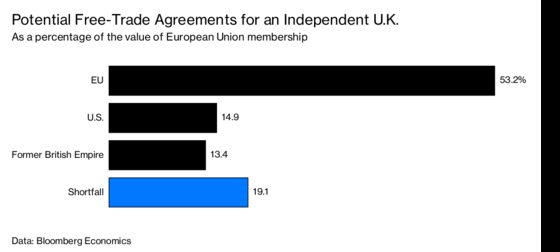

Prime Minister Theresa May’s government in London is promising to create a new “global Britain,” forging its own trade deals after loosening ties with the EU, the world’s richest economic alliance. The U.K. will no longer be dependent on Brussels to open up export markets. It will also be able to choose who comes into the country, shunning low-skilled workers and focusing on the best and brightest. Yet no matter how well it all goes, replacing the economic value of EU membership looks close to impossible.

“People talk about free-trade agreements as if they deliver free trade, and they don’t,” says Grant Lewis, an economist at Daiwa Capital Markets who worked as a U.K. Treasury official in the late 1990s. “The only true free-trade agreement is that within the EU, where you have no regulatory barriers and no trade barriers. That doesn’t exist anywhere else.”

May has spent recent weeks in Parliament trying to get the Brexit deal she struck with the EU in November over the line. The accord is designed to reconcile popular support for taking back control of immigration with corporations’ desire to align with the EU’s open market. Most important, it avoids the “no deal” scenario, wherein Britain leaves the bloc without any framework for continuing to do business with it. So far, May’s agreement has pleased few, and she already postponed a vote by lawmakers once because it faced certain defeat. Parliament is now set to decide on Jan. 15.

The prime minister toured the country before the holidays, trying to rally her divided Conservative Party and put her ministers in front of TV cameras to drum up support for what she says is the only deal they’re going to get. During her Christmas break, she called European leaders to persuade them to make the right noises on the agreement’s biggest sticking point: maintaining the open border between Northern Ireland, a U.K. province, and the Republic of Ireland, an EU member state. May’s critics have expressed the fear that Britain may be locked into the EU’s customs arrangements simply to avoid reintroducing checkpoints at the border, after freedom of movement between the two helped end decades of sectarian violence that ravaged the North. What’s more, May relies on a pro-U.K. party from Northern Ireland for her majority in Parliament.

The discord leaves the Damoclean sword of exiting the EU without an agreement on future trade with the Continent still hanging over Britain. Bloomberg Economics analyst Dan Hanson estimates a free-trade pact with the U.S. would make up less than 15 percent of the economic hit to Britain from a no-deal Brexit. Agreements with a group of countries representing the old British Empire—including Australia, Canada, and India—would make up only about 13 percent or so. EU membership boosted living standards in the U.K. twice as much as free-trade pacts would have done, Hanson estimates. Unless Britain makes an individual deal with every country on the planet and also unites behind one with the EU, it stands no chance of coming close to the status quo, let alone exceeding it.

Britain never really bought into the postwar European integration project. World War II imagery is a mainstay of political speeches in the U.K., and the empire remains a source of pride. According to a 2016 poll, 44 percent of people said they were proud of their history of colonialism, compared with 21 percent who regretted it.

When Europe began to draw together in the 1950s, many saw the grouping as an organization for beaten or invaded nations. The U.K. applied to join once the economic advantages became clear, finally winning membership in the European Economic Community, the precursor to the EU, in 1973. Two years later, it held a referendum on whether to stay. The public, sold on the common market, responded with an emphatic “Yes.” But the relationship was always troubled. In the fallout from the global financial crisis a decade ago, rising poverty and government spending cuts transformed a political squabble over EU control into an existential crisis.

Each side of the Brexit argument accuses the other of lies and scaremongering. Opponents say the country will be poorer, struggle to fill jobs, and have less clout in the world. Brexit advocates say the longer-term benefits of unshackling from EU bureaucracy will outweigh any short-term pain. “In the 19th century, we were the first country to remove tariffs and trade barriers, and that was why we became richer than anybody else—until others started copying us,” says Daniel Hannan, a Conservative member of the European Parliament. “The idea that we couldn’t be a more open and more liberal economy outside the EU is just absurd.”

The problem for Hannan and other prominent Brexit proponents is that even their own numbers don’t add up. Asked to assess the impact of Brexit, the government reported back that Britain would be worse off after any outcome compared with remaining in the EU. The Bank of England’s worst-case scenario for a chaotic Brexit saw the economy shrinking 8 percent within a year. Arguably the more alarming analysis is that even a deal that maintains close ties with the EU would see the economy take a hit of close to 4 percent by the end of 2023.

Brexit campaigners largely dismiss the doomsayers. “A lot of people would love to swap their problems for ours,” Hannan says. And yet, Britain’s forays into the new world may be unfortunately timed. Just as better global growth has helped cushion the blow of Brexit dysfunction, a predicted slowdown in 2019 could compound the U.K.’s pain. The global trade wars instigated by Donald Trump, meanwhile, have altered the state of play. Cultural links with the old empire were talked up by the Leave campaign as a fertile opportunity for dealmaking. But with the tearing up of traditional trade relationships not only allowed but encouraged, a shared interest in cricket or the monarchy may mean little.

“They might love the Queen, the English language, and us giving them money,” says Ed Davey, who served as a business minister from 2010 to 2012. “But they remember parts of the colonial history we might have forgotten, see that the Chinese now give them more money, and have noticed we’re leaving the EU. Many Brexiteers seem to have a sepia-tinted 1950s view of Britain, but the reality is other countries will take a hard-nosed approach.”

After punching above its weight for centuries, the U.K. remains influential within the United Nations—it’s one of five permanent members of the Security Council—and as the most prominent American ally when it comes to intelligence sharing and military planning. To Brexit supporters, that influence stands to grow once Britain gains its independence from the EU. To others, it looks like a delusion of grandeur, as the country has been in decline since 1945.

“We have gradually struggled with that cognitive dissonance,” says Christopher Hill, a professor of international relations at Johns Hopkins University’s SAIS Europe in Bologna and author of a forthcoming book, The Future of British Foreign Policy: Security and Diplomacy in a World After Brexit. “Are we still at the top of the international league table, or do we have to accept the consequences of our relative decline?”

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Jillian Goodman at jgoodman74@bloomberg.net, Rodney Jefferson

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.