How Fast Can CalPERS’s $360 Billion Grow?

How Fast Can CalPERS’s $360 Billion Grow?

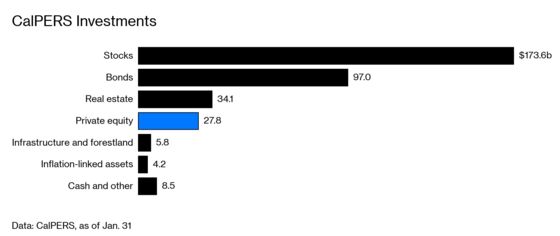

(Bloomberg Businessweek) -- In January, Ben Meng started his job as chief investment officer of a seriously big fund: the $358.4 billion California Public Employees’ Retirement System, or CalPERS, the largest U.S. pension. But neither the scale nor the political spotlight that comes with the role seems likely to intimidate him. For the last three years, he was deputy CIO at the State Administration of Foreign Exchange (SAFE), the tightly controlled $3 trillion reserve fund in China. “It’s not often that an individual has the opportunity to hold key roles for two of the largest pools of capital in the world,” wrote Stephen Schwarzman, chief executive officer of private equity giant Blackstone Group LP, in an email.

Perhaps more daunting for Meng is this figure: 7 percent. That’s CalPERS’s annual return target. It may not sound very high given that the S&P 500 returned almost an annualized 11 percent in the five years through January 2018. But CalPERS made only an annualized 6.3 percent in that period. And deep into both a bull market and economic expansion, there may not be a lot of easy gains to be made from here.

The stakes for CalPERS are high, since missing the mark too widely endangers retirement payments for its 1.9 million members. “We need to do things differently,” says Meng in his Sacramento office. The walls are still bare, and the furniture arrangement is in flux as he tries to find a place where the sun’s glare won’t hit his computer screen.

Meng’s plans to improve returns hinge on private equity. Unlike owning stocks and bonds, investing in private equity funds means holding illiquid stakes in companies that may take years to realize their value. In theory, such investments can play to the advantage of CalPERS as a very long-term investor. Money managers who ignore their institution’s innate strengths and weaknesses, he says, “are the profit center for the other people.”

But CalPERS also faces private equity capacity constraints—it may have more money than it can profitably invest. Its $45 billion allocated to private equity includes $17 billion in uncommitted capital. It needs to place $10 billion a year just to keep up with growth and replace funds that have reached the end of their investment terms. And it’s competing for deals as the private equity industry’s dry powder—money it hasn’t invested yet—climbed to a record $1.2 trillion at the end of 2018, according to Preqin Ltd. That’s a sign that private equity, too, may not offer the bargains it once did.

Meng is exploring a range of options to find opportunities, including creating funds to buy late-stage startups and other companies CalPERS could hold for the long term, competing head-to-head with some of the pension’s longtime partners, such as Schwarzman’s Blackstone. He says he’ll need five years to hire the investing talent and change the culture at CalPERS to implement his vision. “For the investment portfolio to show the effect, it may have to take 10 years,” he says.

He passed his first political hurdle on March 18, when the board endorsed his plan to invest $20 billion in startups and long-term company holdings. “It may or may not work now,” he told the board. “We will not know if we don’t try. And in this challenging capital market environment, we owe it to all our stakeholders to explore all the options available.” Skeptics, including State Controller Betty Yee, a CalPERS board member, questioned whether it’s a good idea. “We’re taking on a larger risk for a future benefit that likely will not move the needle,” said Yee, who voted against the plan.

Meng was born in the Chinese port city of Dalian, the youngest of two sons of an engineer and a history teacher. It was 1970, a year before President Richard Nixon reopened U.S.-China relations and almost a decade before Deng Xiaoping began reforms that launched China’s transformation into a global economic superpower. “If I were born 20 years earlier, I wouldn’t have had the opportunity to leave China and go to the U.S.,” he says. “I was born in an era when you didn’t have to be from a rich family to be successful.”

He came to the U.S. in 1995 for a Ph.D. program in civil engineering at the University of California at Davis. His new California friends were all buying stocks, making a bundle on the dot-com bubble, so he opened an E*Trade account, bought tech stocks, and watched the money grow. He enjoyed investing so much that he enrolled in a new financial engineering program at UC-Berkeley. To pay tuition, he sold his stocks—just before the market crashed. “Dumb luck,” he says. “I didn’t know the difference between alpha and beta.” That’s investment jargon for beating the market and tracking it, respectively. “I didn’t know about bonds,” he adds.

After earning his financial engineering degree in 2002, he worked at Morgan Stanley, Lehman Brothers, and Barclays Global Investors. Then he joined CalPERS in 2008, when the financial crisis sent the fund plunging 24 percent. He focused on a variety of investment areas, helping CalPERS dig out of its hole. He became a U.S. citizen in 2010.

In 2015 he took the job in China to broaden his work experience, he says, but also to be close to his recently widowed mother, who still lives in Dalian with his brother. Meng says he’s not permitted to go into detail about his work at SAFE, where he advised the CIO through last year. “They manage the foreign exchange reserves for China, so that’s an even bigger challenge than CalPERS,” says William Overholt, a senior research fellow and China specialist at Harvard’s Kennedy School of Government. The reserves include international currencies (mostly U.S. dollars), gold, and other foreign exchange assets, according to SAFE’s website. Overholt says SAFE and the People’s Bank of China, the central bank, are “two entities but closely joined.” China’s exchange rate management—sometimes called “ manipulating” by President Donald Trump—is one of the key trade disputes between the world’s two largest economies.

Meng declines to wade into a politically charged discussion about U.S.-China relations. He says his big takeaways from SAFE were developing professional relationships and working on a huge scale. “Once you see $3 trillion, to go to $350 billion is helpful,” he says. “When you work in another country, you see things from an entirely different perspective—you’re right there, right in the middle of things.”

Having lived outside China for 20 years, Meng says he felt like a visitor when he returned for work. He stayed in touch with his former colleagues at CalPERS, and he applied for the CIO job there as soon as he heard of its opening last year. His return to Sacramento has been easy in some respects, he says. He even moved back into the house he bought in 2012 and never sold, as if he were “maybe subconsciously thinking I was coming back.”

He says he took the CalPERS job for the mission, “to serve those who serve California.” His 2019 maximum pay is $1.7 million, including a performance-based bonus. Amid all the big numbers he manages, Meng sometimes struggles to keep things in perspective. “When I make an investment decision at CalPERS or anywhere, it can easily be a half-billion dollars,” he says. “Then I think about the average retiree making less than $3,000 a month from CalPERS.”

Meng tells a story to illustrate how, in money management, nothing is guaranteed. After he got the CalPERS CIO job, his mother was so proud that she opened a brokerage account in China. She would phone her son from China every day to ask if her stocks were going up, and he would reply that he couldn’t be sure. After a while, she stopped calling. “My brother told me she got really worried about what I’m doing,” he says. “How can I manage other people’s retirement money if I can’t even talk to my mother with certainty?”

Investors can, at best, learn the odds and play them in their favor, he says. “The market is not an accommodating machine,” he says. “It doesn’t give you 7 percent every year just because you need it.”

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Pat Regnier at pregnier3@bloomberg.net

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.