California Struggles to Sprawl in an Environmentally Responsible Way

California Struggles to Sprawl in an Environmentally Responsible Way

(Bloomberg Businessweek) -- The Los Angeles County Board of Supervisors voted 4 to 1 in April to give final approval to plans for Centennial, a 19,333-home planned community with more than 10 million square feet of commercial space situated 60 miles north of downtown Los Angeles. Dozens of representatives from trade unions and working-class neighborhoods had urged the supervisors to approve the plan, calling it a case study for how to develop a community. They described the urgent need for housing in the county, where the median home price was $618,500 as of Aug. 1, according to Zillow, up from $350,000 seven years ago.

“This is key to the long-term health of our local economy,” says Jerard Wright, policy manager with the Los Angeles County Business Federation, which asked the county to approve the project. “It is a rare case where firefighters, nurses, young professionals will get an opportunity to purchase a home.”

And yet some environmental advocates want to kill the development. The reason: the potentially long drive to work for the people who’d live there. For the last 50 years, and particularly since the election of President Trump, California has been a leader in environmental regulation. It was the first state to establish tailpipe emission standards for cars in the 1960s, and its 2012 Advanced Clean Cars program aims to reduce greenhouse gas emissions from new vehicles by about 40% by 2025.

But the California Air Resources Board last year reported that the state is falling short of some of its goals. A large part of the problem, according to its report, is the increasingly long commute many Californians have been forced to make: More than 500,000 residents had a one-way commute longer than 90 minutes in 2018, according to U.S. Census Bureau data. That outweighs all the benefits of cleaner, more fuel-efficient vehicles.

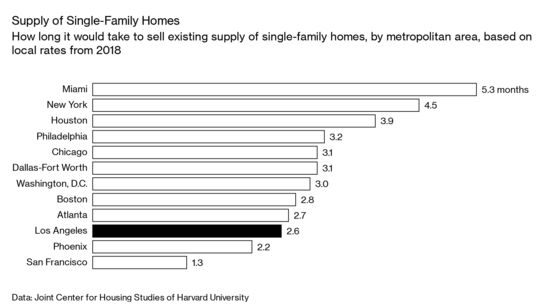

“Los Angeles is the poster child of sprawl,” says Alejandro Camacho, director of the Center for Land, Environment, and Natural Resources at the University of California at Irvine, referring to the city’s endless landscape of single-family homes spreading through the surrounding valleys and down the coast. “From a political perspective, it’s understandable to approve a development like this, because of the need for housing, but the challenge is to build that housing closer to where the jobs are.”

As in most states, land-use decisions in California ultimately fall to local governments, where lawmakers face pressure from developers and home-seekers. There’s still a lot of money to be made by so-called leapfrog development, building communities away from existing cities, says Ethan Elkind, director of the Climate Program at the Center for Law, Energy & the Environment at the University of California at Berkeley. It’s relatively inexpensive to build on undeveloped land compared with infill construction, and those savings are often reflected in home prices. Many working-class families are so desperate for a place they can afford, they’re willing to drive as far as necessary.

State policymakers have called for new housing in urban areas and near transit hubs. Suburban homeowners across the state have so far successfully fought attempts to allow high-rises in neighborhoods zoned for single-family homes. A bill in the California Senate that would make it easier to build apartments in low-density neighborhoods close to jobs was shelved in May after fierce opposition.

“We believe that in California there’s not only a need for additional housing in existing communities, there’s also a need for new communities,” says Barry Zoeller, a senior vice president with Tejon Ranch Co., the developer behind Centennial. The model for Tejon Ranch, he says, is the Irvine Co., a private real estate investment company that in the 1960s developed agricultural land into the city of Irvine. The master-planned community of more than 250,000 has become a thriving economic hub that’s been the headquarters of Broadcom, Allergan, and Blizzard Entertainment. The median household income in Irvine was $94,000 last year.

In addition to Centennial, Tejon aims to develop two other residential communities in the surrounding area: one near the Tejon Ranch Commerce Center, a warehousing and distribution hub along Interstate 5 used by Ikea and Caterpillar Inc. among others, and an upscale resort in the mountains about 8 miles south of there. In 2008 the company made a deal with the Sierra Club, the Natural Resources Defense Council, and other environmental groups to set aside 90% of its land for conservation in exchange for their not fighting its developments.

The Center for Biological Diversity, which wasn’t part of that agreement, has filed several suits seeking to prevent Tejon Ranch from moving forward with its plans. Most recently it argued that the project’s environmental impact report fails to adequately disclose, analyze, and mitigate the harm a city of 57,000 residents will do to grasslands and wildflowers. “Centennial is fundamentally incompatible with the state’s climate goals,” says J.P. Rose, an attorney with the activist group. “It’s a clear example how we’re moving in the wrong direction.” In its lawsuit, the organization also says the site has been designated a very high or high fire severity zone, sitting at an intersection of two mountain ranges with rolling hills, steep grades, and often gusty winds.

Los Angeles County Fire Department Chief Daryl Osby said at the December hearing that he was comfortable with the proposed development, which will utilize nonflammable building materials and fire-resistant vegetation. That reassurance wasn’t good enough for County Supervisor Sheila Kuehl, whose district was devastated in the Woolsey Fire in November. At the hearing, she pointed out that even if Centennial incorporates the most advanced fire-resistant materials, it will still require scarce resources from emergency responders in case of a widespread wildfire. “We are still going to defend these houses,” Kuehl said. “We’re not going to say, ‘Oh well, you built them so they don’t burn, so that’s fine.’ ” She was the only supervisor to vote against the plan.

In the end, Centennial may be no different from other planned cities that have gone up around Los Angeles in the past 50 years. Many started out as bedroom communities but developed into job centers, says Bill Fulton, director of Rice University’s Kinder Institute for Urban Research in Houston. Tejon Ranch expects strong commercial demand and projects that half of its residents will work within the community. “Policymakers are saying you have to build anything but that,” Fulton says, referring to rambling exurbs. “But it’s a real Rubik’s Cube to meet real housing goals within the constraints of state policy.”

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Jillian Goodman at jgoodman74@bloomberg.net

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.