How Surfing Became the Key to Orange County’s Political Future

How Surfing Became the Key to Orange County’s Political Future

(Bloomberg Businessweek) -- “Gavin Don’t Surf” became a rallying cry of last month’s failed effort to recall California Governor Gavin Newsom from office, as frustrated surfers attempted to punish him for closing beaches during the pandemic. Now surfing may play an outsize role in the state’s 10-year redistricting process.

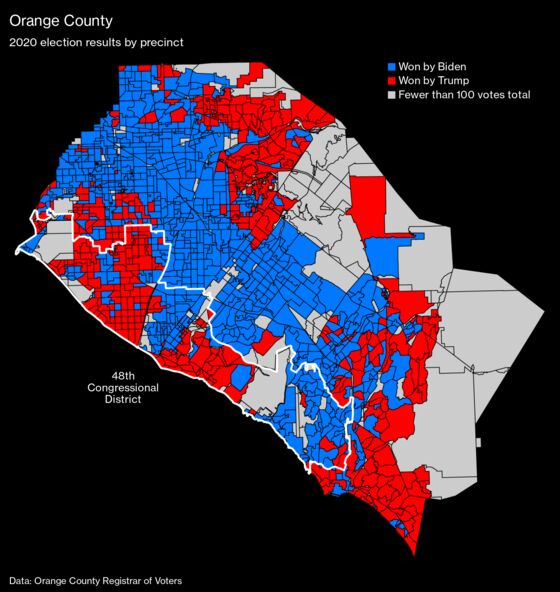

The pastime has long defined the carefree culture and tourist economy of Orange County in Southern California, and tinged the area’s politics: Republican Dana Rohrabacher, an enthusiastic surfer, represented the coastal 48th Congressional District for three decades before being wiped out in the “blue wave” election of 2018. (Michelle Steel won the district back for the GOP in 2020.)

California’s mapmakers will soon decide whether to keep the district as a coastal enclave or to redraw the map so coastal towns are joined with areas further inland. Surfers and other ocean lovers have argued they need to remain in a single district so they can speak with a unified voice in Washington. The seemingly nonpartisan issue could help shape the political future of Orange County, a traditional Republican stronghold where Democrats have been making gains.

To combat gerrymandering, California and six other states have taken the job of redrawing congressional boundaries out of the hands of partisan legislators and given it to independent panels. The state requires the panels to group together communities with shared social and economic interests. But such “communities of interest” are often proxies for partisanship, especially as the U.S. becomes increasingly polarized along lines of income, education, and race. And defining them can be subjective and fraught with controversy.

In Orange County, which hugs the Pacific just south of Los Angeles, some residents say that keeping coastal neighborhoods together would help promote the vital tourism that surfing brings and the lifestyle that goes with it.

“Our south beach cities have a lot of familiarity with the other south county coastal towns,” world champion paddle-board surfer Candice Appleby said at a recent public hearing held as part of the redistricting process. “Things like our ocean and beach tourism, beach erosion, homelessness, ocean conservation—all of which are issues that are really close to my heart and also a big part of our local economy.”

Appleby’s remarks were echoed by dozens of others in testimony and written comments to the California Citizens Redistricting Commission. A common theme: The Orange Coast needs united representation to advocate on issues of ecology and tourism.

“We depend on tourism, more so than inland neighborhoods,” says Patrick Brenden, a former Huntington Beach councilman who’s now chief executive officer of the Bolsa Chica Conservancy, a coastal-ecology education group. “Putting all coastal communities in one district would also benefit inland communities, because their representatives could focus on their unique issues, free from the dynamic, ever-changing issues on the coast.”

The ocean-related businesses contribute 51,000 jobs and $3.7 billion a year to Orange County’s economy, according to a 2015 study commissioned by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. The largest share of that, more than $1 billion, comes from ocean-related tourism and recreation.

Huntington Beach, with a population of 198,711, brands itself as Surf City USA (the moniker prompted a trademark dispute with Santa Cruz, six hours to the north; Huntington Beach prevailed in 2006). It’s home to Boardriders Inc., which includes the Quiksilver, Billabong, and Roxy brands of boards and apparel, and the surf forecasting company Surfline\Wavetrak Inc., as well as dozens of retail surf shops, the annual U.S. Open of Surfing, and the Surf Walk of Fame.

Surfing historian Scott Laderman says that while issues like coastal preservation and beach access can galvanize surfers, there’s not much else that unites them politically. “Looking historically at the surfing community, they tend to be an apolitical bunch,” says Laderman, author of Empire in Waves: A Political History of Surfing. “Most surfers will tell you that’s what they like about it—it allows them to transcend the everyday concerns that they might otherwise have to deal with and escape the social, economic, political turmoil of the outside world.”

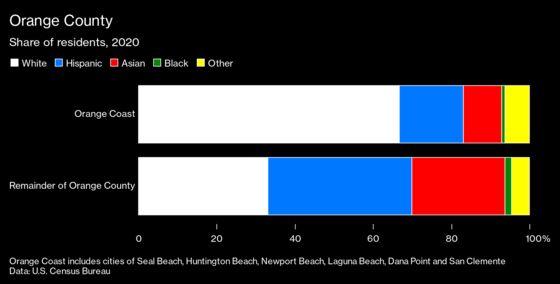

But there are commonalities that have little to do with recreation, Laderman notes. “These tend to be overwhelmingly White, upper-middle-class areas,” he says. “There’s this localist strain that if this beach is in my neighborhood, then I have rights to the wave that other people don’t have. And that localist strain tends to be a very White, privileged one. It’s probably easier from a redistricting point of view to identify that as a surfing community of interest than a White, wealthy community of interest. That probably wouldn’t fly very well.”

Indeed, some coastal residents have pointedly asked the state’s mapmakers to keep them separate from the “high density, political activism, and high crime” of neighboring communities such as Long Beach, which sits across the county line in Los Angeles County and is about 43% Hispanic. Unlike Long Beach, one resident wrote in comments to the commission, Orange County’s beach communities are “very mellow” and the “demeanor is chill.” CalMatters, a nonprofit news organization, reported in September that some of those advocating for a coastal district were prominent local Republicans who didn’t disclose their party affiliation in their testimony to the commission.

“You can’t discuss any of this without discussing the role of class and race,” says Fred Smoller, a political scientist at Orange County’s Chapman University who’s documented the county’s slow transition from a bastion of Reagan Republicans in the 1980s to the more competitive battleground it is today.

Not everyone agrees that keeping coastal communities together is the best way to carve up the county. “It’s clear that there’s an organized effort to persuade this commission to group the entire coastline of Orange County into one district,” says Ada Briceño, a union organizer and the chairwoman of the Orange County Democratic Party (a role she also did not disclose when testifying). She wants a map that divides the Orange Coast, which would reflect the “very different communities” in the north and south of the county, she says: “If you drive around the northern cities where I live, you’ll see working-class neighborhoods, many diverse communities, immigrant communities, and RV parks,” she says. “By comparison, the southern coastline is the version of OC that most people see on TV, with world-class surfing and well-maintained streets.”

Splitting the district would almost inevitably result in a loss of a Republican seat. The four districts surrounding the current 48th are all represented by Democrats.

It’s not unheard of for districts to coalesce around local industries. Coal mines in western Pennsylvania, oil refineries along the Gulf of Mexico, and tourism in central Florida have all been used to draw legislative maps. Still, Orange County’s surfers will have to compete with other interests.

“Certainly there seems to be a concerted effort to make the commission aware of coastal concerns,” says Sara Sadhwani, chairwoman of the 14-member redistricting commission. “But another key piece—and this is something we’ve heard many times over—is that there’s a real need to think about low-wage workers, immigrant communities, communities that might not have been the centerpiece of Orange County in the past, or what you thought of as Orange County. And of course Orange County is home to one of the largest Vietnamese communities outside of Vietnam.”

The county’s nail salon workers are also asking for recognition in redistricting. More than 70% of them are Vietnamese, and while the salons they work in are spread out, most manicurists live in and around Little Saigon, which straddles the cities of Garden Grove and Westminster. They should be kept together politically, says Caroline Nguyen of the California Healthy Nail Salon Collaborative, which represents workers at more than 200 nail salons. “As the demand for nail services continues to rise, it is vital that we sustain the political presence and cohesion of a workforce that has been facing a long-overlooked epidemic of health, socioeconomic, and labor concerns,” she testified to the commission.

Asian Americans account for all of Orange County’s population growth over the past decade, with the percentage of people identifying as all or partly Asian increasing from 20% to 25% during that period. At the same time, the White population declined from 61% to 43%, according to the 2020 census. Demographics are rapidly changing the county’s voting patterns. The county has voted Democratic in the last two presidential elections. Yet Republicans in 2020 won two of the county’s six congressional districts. Both Republican winners were Korean-American women: Steel and Young Kim, whose northern district includes Yorba Linda, the birthplace of President Richard Nixon.

The Democratic Congressional Campaign Committee is targeting both of the districts and is heartened by the results of the gubernatorial recall election. Newsom won Orange County in 2018 with 50.1% of the vote, but 52.4% voted to keep him in office in the recall.

“This was the place where Ronald Reagan said good Republicans came to die,” Smoller, the political scientist, says. “Now I think Orange County doesn’t know what it is—it just knows it doesn’t want to be Los Angeles. They want to retain their separateness, but they’re holding on by their fingertips because, like the rest of the country, it’s going to be majority minority.”

Read next: Atlanta’s Wealthiest and Whitest District Wants to Secede

©2021 Bloomberg L.P.