Prospective Hires Plied With $1,500 Signing Bonuses and Pizzas

Prospective Hires Plied With $1,500 Signing Bonuses and Pizzas

(Bloomberg Businessweek) -- Early in the Covid-19 pandemic, Melissa Anderson laid off all three full-time employees of her jewelry-making company, Silver Chest Creations in Burkesville, Ky. She tried to rehire one of them in September and another in January as business recovered, but they refused to come back, she says. “They’re not looking for work.”

Sierra Pacific Industries, which manufactures doors, windows, and millwork, is so desperate to fill openings that it’s offering hiring bonuses of up to $1,500 at its factories in California, Washington, and Wisconsin. In rural Northern California, the Red Bluff Job Training Center is trying to lure young people with extra-large pizzas in the hope that some who stop by can be persuaded to fill out a job application. “We’re trying to get inside their head and help them find employment. Businesses would be so eager to train them,” says Kathy Garcia, the business services and marketing manager. “There are absolutely no job seekers.”

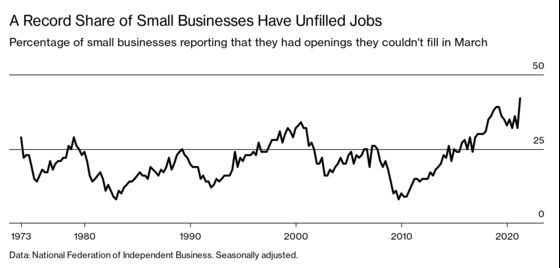

These are anecdotes, but they’re borne out by statistics. On April 1 the National Federation of Independent Business reported that in March a record-high percentage of small businesses surveyed said they had jobs they couldn’t fill: 42%, vs. an average since 1974 of 22%. Also 91% of respondents said they had few or no qualified applicants for job openings in the past three months, tied for the third highest since that question was added to the NFIB survey in 1993.

Here’s another sign that workers feel empowered: The Bureau of Labor Statistics reported in March that the number of people quitting jobs hit 2.3% of overall employment in January, just a tenth of a percentage point below the record going back to 2001.

What makes these figures surprising is that the unemployment rate in March, though well off its peak of 14.8% a year ago, was still 6%. That’s well above the 3.5% rate of February 2020, before the pandemic. So judging from the jobless rate, which the Federal Reserve tracks closely, there’s still plenty of slack in the labor market. But that’s not how employers and job counselors see it. There will be even less slack in coming months as the economy strengthens. The median forecast of economists surveyed by Bloomberg is that the jobless rate will fall to 4.5% in the second quarter of 2022.

There’s some evidence for the conservative argument that generous unemployment benefits discourage people from seeking work. Anderson, the jewelry maker, says her ex-employees told her they preferred to stay unemployed—even though you’re not supposed to collect jobless benefits if you’re turning down work. The American Rescue Plan that Congress approved last month provides an extra $300 a week in jobless benefits through Sept. 6. “There still will be some people who say, ‘I’m glad to take my $300 to $400 a week and stay home, rather than go out and work and earn $500 a week,’” BTIG LLC analyst Peter Saleh, who covers the restaurant industry, told Bloomberg in March.

Covid is also clearly part of the problem. Fear of it keeps some would-be workers home, especially in customer-facing businesses. And with schools closed by Covid, some parents are turning down work to care for children, says Holly Wade, executive director of the NFIB Research Center. Also, she says, the small businesses in the NFIB survey may have trouble competing for workers with the likes of Amazon.com Inc., whose worldwide employment grew 63% last year, to 1.3 million.

Plus, some would-be workers may have lost their gumption. “I’m worried that after all this time that’s gone by, it’s going to be very hard for a lot of people to come back full time. It’s just asking an energy level that people haven’t had in a while,” says Garcia, the job counselor in California. She says a full-time job “used to be the gold standard,” but now employers are parceling out the work into part-time jobs to lure applicants.

Alienation from work is most common among the young. A Pew Research Center survey in October found that 53% of those ages 18 to 29 who are working remotely because of Covid said it was difficult for them to feel motivated to perform their duties. Only 20% of those 50 and older said the same.

On the social network Reddit, which skews young, a forum called r/antiwork has 264,000 members. It’s filled with comments such as: “You’re telling me I have to enslave myself to all these applications for hours on end, competing with my fellow man and woman, giving up my dignity just for a chance to enslave myself further so I don’t literally die? I’m not having it.” One Redditor posted a video of a home computer’s mouse that’s connected to a swiveling fan so it slides back and forth, making it appear the person is working.

This isn’t to say that every unemployed person is alienated or that anyone who wants a job can get one. Tightness in the labor market varies by occupation and geography. The March unemployment rate was 15% in mining, quarrying, and oil and gas extraction, and 13% in leisure and hospitality. By contrast, it was just 2.7% in government (which includes public school teachers) and 3.4% in financial activities. Hawaii had the nation’s highest unemployment rate in February, 9.2%, while South Dakota had the lowest, 2.9%.

Many of the jobs that employers can’t fill are low-paying, while the high-paying ones generally require skills that most people don’t have. The pandemic accelerated digitization of work, creating shortages of talent in such fields as artificial intelligence, machine learning, data analysis, security, and network engineering, says Lisa Lewin, the chief executive officer of General Assembly, a training company owned by Adecco Group.

Employers would have an easier time filling job openings if they raised pay or got less picky about qualifications. Re’gine Johnson, 26, of Chicago said she interviewed with 40 companies before she landed a job, even after completing a three-month General Assembly boot camp in user interface design. “They’re thinking, ‘Do we really want to invest in somebody that’s so junior, do we have the time to teach them something they may not know?’” she says. She’s thriving now at Neon One LLC, the software company that hired her and provided on-the-job training.

Employers are going to have to adjust to a world in which workers are harder to get. In Cleveland, manufacturers are striving to change the outdated impression that their jobs are dirty, boring, or dangerous because recruitment shortfalls are forcing them to turn away orders, says Ethan Karp, president and CEO of Magnet, a nonprofit consultancy. “It’s their No. 1 problem,” he says. —With Leslie Patton

©2021 Bloomberg L.P.