Bud Selig Was Baseball’s Great Hero, Says Bud Selig

Bud Selig Was Baseball’s Great Hero, Says Bud Selig

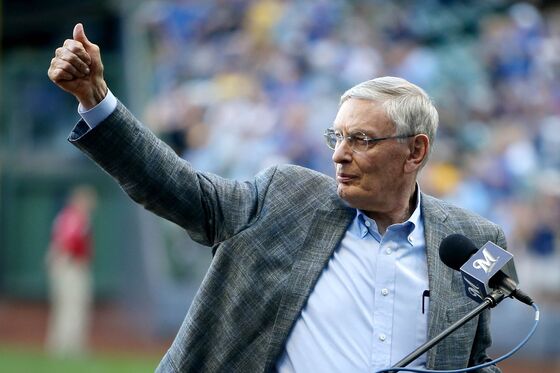

(Bloomberg Businessweek) -- For 22 years, from 1992 to 2015, Bud Selig oversaw Major League Baseball, an era of massive change and growth for America’s Pastime. He restructured the league’s divisions and playoffs, initiated interleague play, introduced the World Baseball Classic, and helped grow a technology arm now worth billions of dollars.

To hear the former commissioner tell it in his new memoir, For the Good of the Game (William Morrow, $29), Selig inherited a “f---ing nightmare” but heroically steered the league through unprecedented labor strife, cleaned up a drug problem that threatened the integrity of the game, and eased an economic disparity between teams that could have put baseball, as we know it, out of business. He uses the book to tout his record on racial diversity, the 20 stadiums built during his tenure, and the introduction of the wild card. The league’s revenue grew from $1.2 billion to more than $9 billion a year over his tenure, and franchise valuations grew even faster.

But some of the stuff here just doesn’t track with reality. He writes that baseball “is thriving,” but attendance has dropped for six straight years—last year’s 69.7 million total was the lowest since 2003. Fans are aging up, and TV ratings are trending down, especially for the World Series. Last year’s event averaged 14 million viewers per game, the fourth-lowest total ever.

On steroids, Selig tries to have it both ways. He says baseball didn’t know the extent of the problem when Sammy Sosa and Mark McGwire were shattering the home run record, but maligns the journalists who gushed over their triumphs then later turned critical—something you could say about his own office. Desperate for fans following the 1994 strike and cancellation of the World Series, the league hyped the home run era. Now, Selig says he was powerless to institute drug testing because of the players’ union.

The revenue-sharing system he introduced is another mixed bag. Richer teams such as the New York Yankees and Los Angeles Dodgers now pay into a pool that’s shared by the teams in smaller markets, like the Kansas City Royals and Tampa Bay Rays. Selig estimates that without it, up to a dozen teams might have gone bankrupt.

Although the system was built to help poorer teams compete for talent, it now seems to be doing the opposite. After the free-agent market remained sluggish for a second straight year, veteran players are voicing concerns that shared revenue gives teams the freedom to be bad and still turn a profit. Some say many teams are no longer trying to field competitive squads. The “system is broken,” tweeted star pitcher Justin Verlander in February.

Born Allan Selig in 1934, he is a baseball lifer. He grew up in Milwaukee and fell in love with the sport at a young age. After a brief stint in the Army he joined his father’s successful car dealership, but when the city’s first MLB team, the Braves, bolted for Atlanta, Selig vowed to bring baseball back. In 1970 he led a group that bought the Seattle Pilots for $10.8 million—which included $300,000 of his own money. The team was renamed the Brewers and moved to Milwaukee.

It’s a classic American dream story. And, thanks to Selig’s success, it’s one we’ll likely never see again. As shiny new stadiums rose and live sports became gold for TV networks, franchise valuations skyrocketed. (All are worth more than $1 billion today.) Gone are the days when a local Ford salesman could rustle up the money to buy a major league team.

Nostalgia, it turns out, is the book’s best feature, thanks to Selig’s perch next to the game’s legendary characters. There’s a scene where late Yankees owner George Steinbrenner criticizes Selig’s revenue-sharing plan by complaining that they “were all turning into socialists.” In another, an irate Selig curses out Vice President Al Gore after the Clinton administration backs out of a plan to resolve the players’ strike. He rides with the FBI during a cocaine bust that snared Brewers star Paul Molitor, and he’s in the Yankee Stadium basement as President George W. Bush—former managing general partner of the Texas Rangers—prepares to throw out the first pitch of the 2001 World Series, weeks after the Sept. 11 attacks. “Don’t bounce it, Mr. President,” Derek Jeter tells him. “You’ll get booed.”

But when it comes to the overall health of the sport, baseball and its fans deserve a less rose-tinted accounting. The current labor agreement expires in two seasons, and already players are voicing their displeasure: Salaries are flat, and long-term deals have been hard to come by. The economics of the sport, as it’s currently constituted, feel untenable, and another labor stoppage is a real possibility.

Those are all problems now for Rob Manfred, Selig’s successor. Selig says he “changed the nature” of the commissioner’s job. Manfred has to handle the fallout.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: James Gaddy at jgaddy@bloomberg.net, Chris Rovzar

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.