Atlanta’s Wealthiest and Whitest District Wants to Secede

Atlanta’s Wealthiest and Whitest District Wants to Secede

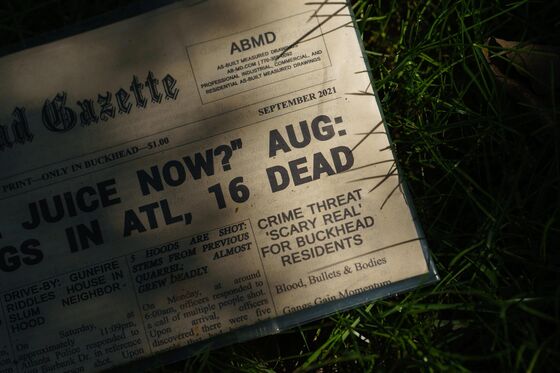

(Bloomberg Businessweek) -- On the night of Aug. 7, Kenon Jennings was found shot near Hide Kitchen & Cocktails, a popular hookah lounge in one of the many booming business strips of Atlanta’s Buckhead area. Jennings later died, becoming one of 65 people murdered in Atlanta as of that week in 2021, compared with 46 murdered during the same period in 2020.

Jennings was also the ninth person murdered in Atlanta’s police Zone 2, which encompasses Buckhead, up from six murders the previous year. For Bill White, who lives in Buckhead, the killing was yet another sign that the area known for its mansions, high-end restaurants, and luxury stores needs to take public safety into its own hands.

“We are living in a war zone in Buckhead,” White says. “Shootings and killings, it just never ends.”

White is the chief executive officer of the Buckhead City Committee (BCC), a group trying to convince lawmakers and voters that the neighborhood should split—or de-annex—from Atlanta and become a city unto itself. There are many political hurdles, but White’s group has already cleared a few of them, and a bill has been introduced in the Georgia legislature to allow the de-annexation to come up for a vote next year. If all goes in the BCC’s favor, White expects the new city to be up and running by June 2023.

The push is part of a movement around metro Atlanta known as cityhood. Since 2005, communities in the region have formed more than a dozen new cities, with several more hoping to incorporate. But Buckhead City would be the first Georgia city to form by breaking off from an existing one.

A split could be devastating for Atlanta financially. Buckhead isn’t small—it stretches over 24 square miles—and the proposed new city would take with it nearly 90,000 residents, about one-fifth of Atlanta’s current population. Atlanta would lose an estimated 38% of its tax revenue if Buckhead leaves, according to the Buckhead Community Improvement District. The Metro Atlanta Chamber of Commerce and two local civic and business groups, the Buckhead Coalition and the Buckhead Business Association, have said they oppose de-annexation.

Buckhead’s secession would strike at the power of Atlanta’s Black political class. Black residents have been involved in a 50-year project to accrue power in the city, beginning with the election of the first Black mayor, Maynard Jackson, in 1973. Today, a mostly Black cast of elected officials is in charge of the largest city in the South, which has one of the highest concentrations of Fortune 500 company headquarters in the nation.

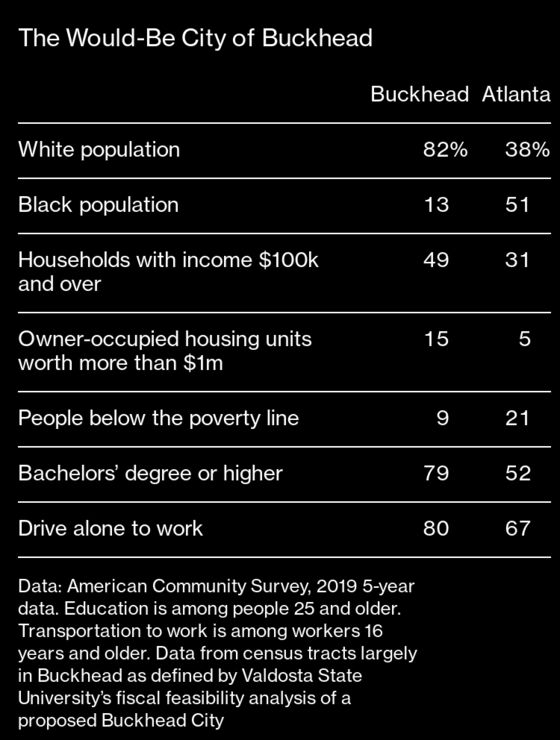

Atlanta as a whole is 51% Black, according to 2019 census data. An analysis by the Atlanta Journal-Constitution found that the new Buckhead City would be roughly three-quarters White.

“I think that much of what’s going on is about the inability of” White Buckhead residents “to have greater influence over the policy choices of the city of Atlanta,” says Michael Leo Owens, a political scientist at Emory University. Buckhead “is among the Whitest parts of Atlanta, and it is the epicenter of Republicanism in Atlanta. All those things map on to each other to create, at a minimum, a racial cleavage, with regards to politics and elections in the city of Atlanta.”

The 30327 ZIP code, representing Buckhead’s plushest quarters, was the only pocket of the city of Atlanta to vote for Donald Trump in 2020. Bill White says the de-annexation push is not about politics or race but simply about the future of the neighborhood: “We are people who just want to take our community back.”

“I’m not a Republican. I’m not a Democrat. I’m not an independent,” White told a group of supporters this spring. “I’m not Black. I’m not White. I’m not gay or straight. I’m none of those things,” he continued. “And we want all of us to start thinking that way because that’s the way we win.”

Past attempts to carve Buckhead out of Atlanta have gone nowhere. This one has gained momentum, thanks in part to the well-connected White, who runs a consulting firm, the Constellations Group. Once a big-dollar fundraiser for Hillary Clinton, White threw his allegiance behind Trump after Clinton’s loss in 2016 and helped raise millions for Trump’s 2020 campaign. He and his husband Bryan Eure moved to Atlanta, Eure’s hometown, three years ago.

Led by White and a local real estate agent named Sam Lenaeus, the BCC has raised almost $1 million for its campaign, according to White. Several local families have given $100,000 each, he says.

“It is more serious this time, and the proponents of it are well funded,” Fulton County Commission Chairman Robb Pitts, who lives in Buckhead, says of de-annexation. “I think it’s going to go further this time around than it’s ever gone.”

A recent poll conducted by the Atlanta Journal-Constitution and the University of Georgia School of Public and International Affairs found that almost 54% of Buckhead residents voiced support for cityhood. The BCC’s own polling puts the share of residents on board with the split at 62%.

White is appealing to donors in a campaign centered on fears of crime. “Really, honestly, truthfully,” he said at a fundraiser in the spring, “we just would like to feel that we’re not going to be shot going to the gas station or out on a jog.”

Opponents of the cityhood idea have mounted their own lobbying group, the Committee for a United Atlanta. Co-Chair Linda Klein, a lawyer and past president of the American Bar Association, says Buckhead’s crime problem is “horrible,” but “some of us disagree on what the solution is.” “If I believed that carving up the city was the solution, I’d be all for it,” she says.

Like many other big American cities, Atlanta has experienced a recent increase in violent assaults and homicides. In the police zone where Buckhead is located, there were 48 shootings this year as of Sept. 11, up 50% from the same period last year and up 167% from the same period in 2019. But it’s hardly Atlanta’s worst area for crime. The Buckhead zone has experienced fewer murders, shooting incidents, robberies, and burglaries in 2021 than any of the five other police zones around Atlanta, as of the week of Sept. 11.

Supporters of a new Buckhead City lay much of the blame for rising crime on Atlanta Mayor Keisha Lance Bottoms, who oversees a police force that lost almost 200 officers last year. Her criticism of tough policing tactics during last year’s social unrest left some on the force demoralized. “This whole thing is her fault,” White says of Bottoms. “This has nothing to do with anything except lack of leadership. Rome is burning. We’ve got to take control back from the crazies who are running these cities into the ground.”

Bottoms, a Democrat, contends that the surge in violence parallels that in other cities and was spurred by restless young people not being in school and by a proliferation of guns on the street.

“Even if an impermeable wall were built around this proposed new city, it would not address the Covid crime wave that Atlanta, the state, and the rest of the nation are experiencing,” she said in a statement. “That is why this measure is opposed by many residents and the business community. A better use of this energy would be to work together to address the challenges facing our city, not to divide Atlanta.”

Bottoms decided not to run for a second term this year, and several candidates are competing to replace her. All of them have said they oppose cityhood for Buckhead.

The Atlanta Police Department defended its work in a response to Buckhead cityhood proponents. “To insinuate that we’re looking the other way when it comes to crime is a far-fetched notion,” the Aug. 4 statement reads. “The APD has more than 150 sworn members assigned to multiple specialized units outside of our Field Operations Division and these resources are utilized on a regular basis in Buckhead and throughout the city. Regardless of where their enforcement activity occurs, it has an impact on crime throughout the entire city, Buckhead included.”

The mechanism to create a new city in Georgia is fairly simple. An organization just needs to find a sponsor in the state’s General Assembly to present a bill in support of its proposal. The sponsor doesn’t even have to represent the district where the new city is being proposed. The Republican sponsor of the Buckhead City bill, Georgia Representative Todd Jones, represents south Forsyth County, about 30 miles north of Atlanta.

If state lawmakers pass the bill next spring, it will then go before voters to decide directly in a referendum. There’s a catch: Only people who live within the boundaries of the proposed new city get to vote on it. The majority of Atlantans would have no say in a matter that would certainly affect them.

According to a fiscal analysis conducted by the Committee for a United Atlanta, de-annexation would cost Atlanta as much as $116 million annually, while Atlanta’s school district could lose almost $232 million every year. A feasibility study undertaken for the BCC found that de-annexation would be a huge boon for Buckhead City. It would bring in an estimated $203 million in revenue annually, vs. $90 million in expenses, according to Valdosta State University’s Center for South Georgia Regional Impact. Some of the expenses would go toward a police department, with at least 250 officers at a starting salary of $55,000, the BCC says.

Before this year, any campaign for cityhood needed to obtain a financial feasibility study conducted by one of three state-authorized universities. State lawmakers recently changed the rule, and now any qualified University System of Georgia school can perform the study. That modification immediately gives Buckhead an advantage that no cityhood campaign before it had.

As for the unprecedented nature of extracting a new city from an existing one, nothing in the state law says that new cities can be created this way—but nothing says they can’t be, either. And this isn’t Georgia’s first dance with city secession. In 2018 a swanky neighborhood anchored by a country club called Eagle’s Landing tried to split from the city of Stockbridge to incorporate on its own.

The proposal made it all the way to a ballot referendum that year, where it failed. Had it been successful, it would have done irreparable economic harm to Stockbridge, wrote Kidwell & Co., a municipal finance adviser that lists several Georgia cities as clients. Moody’s Investors Service and S&P Global Ratings said the secession would have negatively affected the credit ratings of Stockbridge, every city in Georgia, and the state itself.

The reason cited was that the Eagle’s Landing case could have led other cities to break up. For the investor firms, this would mean “weakened predictability” over whether jilted cities would be able to continue to honor debt obligations, such as municipal bonds and pensions, if they lost major portions of their taxpaying populations.

There were lawsuits to stop the secession vote from happening, but when the Eagle’s Landing ballot failed, it rendered the lawsuits moot, which means the legal questions remain unresolved.

Still more hurdles lie ahead for the Buckhead campaign, such as a state requirement that it demonstrate the new city wouldn’t financially injure Atlanta by de-annexing from it. The BCC says it won’t harm Atlanta and will divert taxes only for police, roads, and parks. But its own math shows the neighborhood accounts for nearly 40% of property tax revenue generated for Atlanta. The Committee for a United Atlanta has echoed the earlier warnings from Moody’s and S&P Global in its fiscal analysis of de-annexation, warning that it “would likely have a destabilizing impact on the State of Georgia.”

A potential ripple effect would be neighborhoods across Georgia branching off into what Owens calls “affinity cities,” whereby boundaries are drawn around people of the same wealth, ideology, and—in many cases—race, deepening geographic segregation.

A mapping project by Trulia and the National Fair Housing Alliance showed that banks, medical centers, grocery stores, parks, and other amenities are disproportionately clustered in Atlanta’s northern neighborhoods in and around Buckhead. The Atlanta Journal-Constitution found that the city’s $60,000 median household income would drop to $52,700 if secession happened. Buckhead City would have a median household income of $140,500.

Whatever the Buckhead campaign’s complaints about it, Atlanta “has done a lot to protect the interests of Buckhead” over the years, Owens says. “Because it’s in the interests of the city of Atlanta to do that.”

Read next: Wall Street Helps Ron DeSantis Amass a Hefty War Chest for 2022

©2021 Bloomberg L.P.