Broadway Is Coming Back In September. But Can It Stay Open?

Broadway Is Coming Back In September. But Can It Stay Open?

(Bloomberg Businessweek) -- After The Phantom of the Opera shut down with the rest of Broadway in March 2020, John Riddle was overcome with relief. “We do shows eight times a week, and you never really have a day off,” says the actor, who plays Raoul, one of the leads. “So for the first two weeks, it was glorious.”

A year and a half later, the thrill has worn off. Riddle, who stayed in New York for much of the pandemic doing street performances, teaching classes on Zoom, and getting the odd outdoor gig, is set to return to rehearsals on Sept. 27 in anticipation of Phantom’s reopening on Oct. 22. But he’s begun to eye Covid‑19-related cancelations in London and Australia with concern. “Now that I have a return date, I’ve sort of based my life around it,” he says. “There’s a little thing in the back of my mind that hopes the world gets it together for our health and safety, but also to bring Broadway back.”

The world has a long way to go. Covid cases are rising in almost every country that tracks them, and New York, which for months had seen case numbers trend downward, is grappling with a series of troubling upswings in all five boroughs. But a smattering of shows still plan to open in September, including Hamilton, The Lion King, Wicked, and Chicago. Dozens more are set to follow through December.

“A week ago, there was great optimism that by Sept. 14 we would be raring to go,” says Charlotte St. Martin, president of the Broadway League, the national trade organization for the industry, speaking in late July. “Now, I would say there’s cautious optimism, what with the delta variant and the many forms of communication coming out that there’ve been breakthrough cases” among vaccinated people. On July 30, Broadway announced that audiences and performers will be required to be vaccinated and that masks must be worn for all performances. But uncertainty about the delta variant could keep people out of crowded theaters, masks or no, and that’s assuming the city and state don’t shut down large gatherings altogether.

So players across the industry are beginning to ask themselves how long they can stay open. “It’s very simple,” says St. Martin: “the way we stay open during any other time, which is with most likely 75% of the seats or more being sold.”

Should ticket sales fall below those numbers, she says, Broadway marquees could quickly go dark. “If we open and go for more than two weeks with low occupancy, the likelihood is that many shows would have to close and most likely not be able to reopen,” St. Martin says.

Several of the shows, she continues, have some buffer because they got Shuttered Venue Operators Grants, part of the $900 billion stimulus package Congress passed in 2020. “I know some of our producers are putting some of that money in reserve to keep the show open,” she says.

There’s also assistance from the city and state in the form of the Empire State Musical and Theatrical Production Tax Credit Program, which provides payroll tax breaks up to 25%, with a $3 million cap per show for the first year. But no matter where the assistance is coming from, “if you really don’t sell any tickets,” says Rent and Six producer Kevin McCollum, “you have to close, and you can’t use the grant.”

Every show attracts a different audience, but the conventional wisdom, St. Martin says, is that during a typical year, 65% of Broadway’s audience is made up of tourists, about 15% of them international.

The remaining 35% of attendees come from the tri-state area, and their makeup varies. “I think the last full season,” she says, “we had 20% New Yorkers and 15% tri-state.” Tourism in 2021, however, is projected to be down by about half from 2019. Making up those numbers with only a regional audience will be hard.

Some shows could fare better than others, but not the ones you might think. Institutions such as The Lion King are “national and international brands,” says Eva Price, a multiple Tony Award-winning producer. Under normal circumstances, wide acclaim would make a steady flow of out-of-towners eager to sign up for a household name.

In a twist, these shows’ decades of success could hurt them. “In a show’s life span, its first year is almost always tri-state and local audiences,” Price says. “Just think about it: Thirty years later, it’s not a bunch of New Yorkers going to Phantom, it’s tourists.”

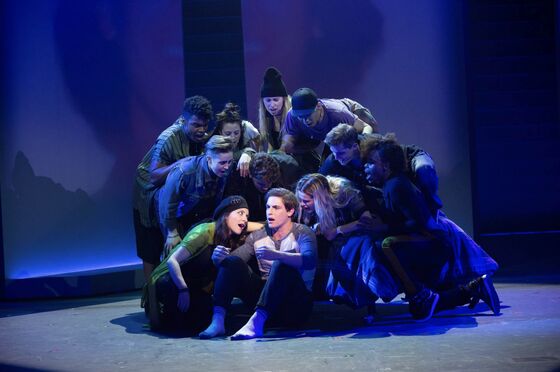

But Price’s Jagged Little Pill, which is based on music from the 1995 Alanis Morissette album of the same name, ran for only three and a half months before Covid shut it down. So she isn’t counting on tourists to keep the show running when it returns to Broadway on Oct. 2. “We feel that between the source material and the awards and the reviews, we have local audiences to make our way through,” she says. “And that’s the five boroughs, as well as the tri-state area and Northeast Corridor.”

Even without the health and safety protocols necessary to make an audience feel safe, keeping a show open this fall will be a very different task than before. “Musicals historically outperform plays,” says Brian Moreland, the lead producer of Keenan Scott II’s highly anticipated play Thoughts of a Colored Man, which is set to open on Oct. 31. “They’re larger, you can get more people into the theater, and if there’s any type of language barrier, it’s OK to watch the singing and dancing.”

This fall, though, “musicals are at risk of suffering because of a lack of tourism—especially when you’re a long-running musical, where possibly you have exhausted the New York audience,” he continues. “Plays have the benefit of being smaller and more on-brand of a time and place.” When that happens, he continues, “it can really appeal to the New Yorker or domestic traveler.”

As long as Broadway stays open, producers will get creative about selling tickets. “The business model of shows will get better and improved when the audience gets wider and more inclusive,” Price says. “I don’t know what other people’s strategies are, but I don’t think it’s about selling less seats, or having fewer shows. It’s about increasing accessibility and building beyond the obvious theatergoing audience—beyond the audience that can afford $150 a ticket.”

That means hiring a marketing team that targets younger people, she says, and developing an audience “of different backgrounds and ethnicities and cultures and classes.”

The challenge for legacy productions, Price continues, is to “change the marketing so people know it’s for them, because the shows are that good.” That’s the thing, she says: Musicals like Phantom “have run for 20-plus years, not because they’re lucky, but because they’re astonishing feats of emotionality and creativity, and this is an opportunity for those shows to create new audiences.”

To date, things are looking good. Ticket sales across the board “have been brisk,” St. Martin says. “But we’re still a couple of months, even three or four months out. Brisk might not be enough.”

Phantom’s Riddle remains optimistic. “I have dates through at least January,” he says. “So right now I’m planning to show up eight times a week, and that’s how I’m approaching it until there’s nobody walking through the doors.”

©2021 Bloomberg L.P.