Brexit Worries Make Seasonal Hiring Harder for U.K. Farmers

Brexit Worries Make Seasonal Hiring Harder for U.K. Farmers

(Bloomberg Businessweek) -- Scottish farmer Tim Stockwell has typically hired agricultural laborers from the European Union, who can travel to pick his strawberries and broccoli without the hassle of visas or work permits. But Brexit uncertainty has contributed to a labor shortage that’s getting worse this year. So Stockwell is booking migrants from non-EU countries Ukraine and Moldova and trying to make the jobs more attractive. He’s doing everything from offering furnished housing to stocking Romanian and Bulgarian food for seasonal workers. Some farmers are even staging disco nights for their temporary pickers.

“It’s just any small things we can do,” says Stockwell, who hires hundreds of overseas workers, mostly from the eastern EU, each year at his 500-acre farm near St. Andrews. “It’s just something that might make them feel more at home.”

Brexit has left U.K. farms struggling to attract foreign workers. Almost half of U.K. farmers reported some crops left to rot in the fields last year as fewer EU workers returned to British farms, amounting to an average loss of £130,000 ($170,000) per business. With immigration a key issue in the Brexit vote, many migrant workers are worried they’ll be less welcome than before or that a weaker pound will dent their earnings.

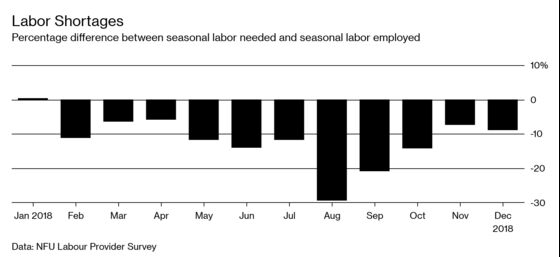

Overseas workers typically fill jobs that Brits don’t want, with growers of soft fruit employing about 30,000 seasonal laborers, more than a third of the temporary horticultural workforce. Farm work in the U.K. pays about £320 a week, with work available from April to November. Farmers were about 9,000 harvest workers short last year, and the deficit will likely rise this year, according to the National Farmers Union. If farmers can’t harvest all their crops or have to pay more to attract workers, that could push up prices of fruit for U.K. consumers—or force the nation to rely more on imports.

For the farm industry, which gets most of its seasonal labor from the eastern EU, the U.K. has started a trial program to help bring in 2,500 workers from outside the bloc on six-month visas. But that’s a difficult and lengthy process compared with recruiting EU farmworkers, who can move freely around the zone. Fifteen Ukrainian and Moldovan workers Stockwell had booked arrived more than two weeks late because of the time needed to complete their paperwork. “If arrivals are delayed a month, that could make the difference of getting a crop and not getting a crop picked in time,” says Stockwell, who typically gets about 90% of his workers from EU members Romania and Bulgaria.

The delayed Brexit deadline isn’t helping either, with uncertainty over the divorce terms stopping many workers from traveling to the U.K. “Recruitment events are seeing fewer people through the doors,” says Lee Abbey, chief horticulture and potatoes adviser at the NFU. “They’re worried about the atmosphere, whether they’ll feel welcome.”

Improving employment or education prospects in Eastern Europe may also reduce the desire to seek work abroad. Some people have more appealing alternatives than harvest work. Fewer Poles have been emigrating to Western Europe in recent years as unemployment has fallen at home. In Romania, “opportunities for students and younger people have absolutely increased, and they’re grabbing them,” says Stephanie Maurel, chief executive officer of Concordia U.K. Ltd., a charity that recruits farmworkers from Eastern Europe. “The choice is five or six months hard labor in the U.K. or Erasmus in Italy,” Maurel says, referring to the EU’s Erasmus university exchange program that gives eligible students monthly stipends to help offset school expenses.

Still, British farmers are counting on many foreigners remaining eager to accept fieldwork. Yelyzaveta Miadzelets, a 21-year-old Ukrainian student, will pick broccoli and potatoes on a Scottish farm this summer under the U.K.’s pilot recruitment program. She says she can earn a lot more in the U.K. than at home, but she adds that money isn’t the most important draw. “First it’s experience,” she says, “then cultural exchange, and then money.” —With Joe Mayes

To contact the editor responsible for this story: James Ellis at jellis27@bloomberg.net

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.