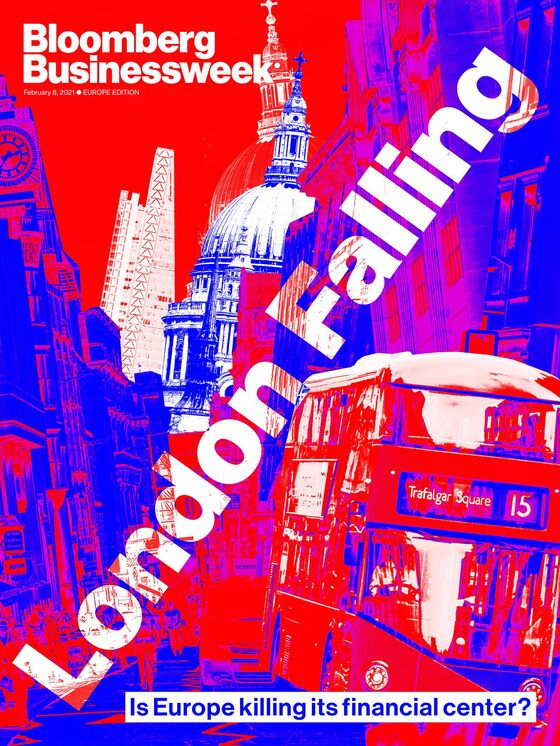

The City of London Is Now at the Mercy of Brexit’s Tug of War

The City of London Is Now at the Mercy of Brexit’s Tug of War

(Bloomberg Businessweek) -- In the beginning was the Big Bang. It was 1986, and the moribund British economy appeared stuck in an unbreakable cycle of postindustrial decline. Then came the jolt that opened up U.K. financial markets to the world and turned the City of London into the nation’s dynamo.

Banks gathered in the Square Mile, and companies flocked to list on the newly deregulated stock exchange. Caricatured gents in bowler hats meeting over tepid ale were displaced by a generation of Gordon Gekko-style traders. More than three decades of near unbroken growth ensued as the Big Bang propelled London to the status of Europe’s preeminent financial center with the vast majority of trading in bonds, euro-denominated foreign exchange, and derivatives.

Now the City of London has to contend with the fallout from a far less auspicious political explosion, and it’s one that could have an equally enduring legacy.

On the first trading day of the year, the impact of Britain’s withdrawal from the European Union became brutally clear. Billions of dollars of buying and selling shares found new homes on exchanges on the continent. At equities trading venue Aquis Exchange, 99.6% of European stock transactions shifted to Paris. Another exchange, Cboe Europe, saw 90% of that business move to Amsterdam. Billions more in derivatives trading then quit for New York, which also stands to gain from the region’s infighting.

Bank of America Corp., JPMorgan Chase & Co., and other big companies moved staff and money to cities such as Paris and Frankfurt to make sure they can continue doing business with European clients. TP Icap Plc, the London-headquartered company that’s the world’s largest interdealer broker, said it could no longer serve all of its EU clients because it hadn’t moved enough staff to Paris. Even with the excuse of a global pandemic that’s prevented all but essential travel, French regulators were unmoved by the firm’s request for a temporary reprieve until restrictions had eased.

The damage isn’t yet fatal, and London has a long history of reinvention. The U.K.’s finance chief, Chancellor of the Exchequer Rishi Sunak, is aware of the risks for an industry that provides 10% of the British tax take and has plans to secure its future. The question is whether Brexit marks the start of an irreversible demise for the City of the Big Bang as thousands of cuts merge into a single bleeding wound. What’s sure is that the future of London as a financial hub is now at the mercy of the political winds on both sides of the English Channel. With the coronavirus still rampant and tensions high over access to vaccines, the omens don’t look good.

It’s not clear the City is a top concern for Prime Minister Boris Johnson’s government. His Conservatives were the instigators of the boom 35 years ago. They’re now desperate to make Brexit work for the poorer regions that voted to deliver a blow to the establishment and the bankers they blamed for the global financial crisis—that is, London. Johnson owes his parliamentary majority, and ultimately the delivery of Brexit, more to blue-collar workers in the north of England than to moneyed supporters in financial services.

“Whatever the post-Brexit, post-Covid rebuild is, it can’t just all be concentrated on London again,” says a former chief executive officer of one of the U.K.’s largest banks. Or as veteran industrialist Nigel Rudd put it: “I don’t think the government is that bothered about the City.”

The EU has stated its intent to snatch what it can from London. Britain’s departure shrank the bloc’s capital markets by a third, according to data from New Financial, a think tank. With Paris or Frankfurt failing to rival the U.K. capital in any meaningful way, the EU is the only economic superpower without a regional financial center under its control—a problem it now has an opportunity to solve. “The EU sees financial services as a jewel that they’re going to poach from the U.K.,” says Nicky Morgan, a Conservative baroness in the House of Lords and a former member of Johnson’s cabinet.

“This isn’t a one-off hit, and then we carry on forever,” says David Gauke, a former Conservative cabinet minister who fell out with Johnson and the party over Brexit. “The risk here is European regulators dialing up over time what they require of financial-service institutions.”

It all comes down to what’s called “equivalence,” or equal access to a market by a nondomestic provider of financial services. Right now, equivalence agreements between the U.S. and the EU mean New York enjoys greater access to the bloc’s financial markets than London. Indeed, because of Brexit, Britain has fewer equivalence deals than its Atlantic overseas territory of Bermuda.

The noises from Brussels aren’t good. “Change is coming,” Mairead McGuinness, European commissioner for financial services, told Bloomberg TV on Jan. 22. Six days later, Jose Manuel Barroso, a former head of the European Commission and now a Goldman Sachs Group Inc. adviser, said there would be no permanent equivalence for financial services.

Talks on the financial-services relationship between the U.K. and EU began in January with a March deadline for agreement on a memorandum of understanding. This will spell out how regulators on both sides will cooperate and, the hope is, provide the basis for the U.K. to win equivalence deals for banks, insurers, and investment firms. The government in London has already said it may take longer.

History tells us London could thrive again, and Britain needs it to. If the City of London is the engine of a capital with 9 million people, London itself is the economic linchpin of a country of 67 million—regardless of the resentment in neglected regions that voted for Brexit.

The Covid-19 pandemic is another force undermining London. Britain has Europe’s highest death toll, with more than 100,000 fatalities nationwide. Hospitals remain stretched even as the country’s vaccine program is way ahead of the rest of Europe’s. A third national lockdown has shuttered stores and the restaurants and nightlife that gave London its buzz. On the fringes of the financial district there are signs of physical decline as moss grows on cafe awnings and boutique hotels built to service City workers shutter.

London’s population is expected to shrink this year for the first time in more than three decades. An estimated 700,000 people have left during the pandemic, according to the U.K.’s Economic Statistics Centre of Excellence. A recent survey of Londoners by recruitment firm Adecco and pollster YouGov Plc found that one in three of the capital’s residents would consider leaving for another European country. In the City, foreign-born staff made up 39% of the workforce in 2018. That may change after stricter post-Brexit immigration rules.

“The whole ‘London vibe’ was how we used to describe it when I was at City Hall,” says Gerard Lyons, a former adviser on the financial industry to Johnson when he was London’s mayor. “One would hope that post-pandemic, the attraction of London, the international vibe, will remain.”

Chancellor of the Exchequer Sunak, a 40-year-old Goldman Sachs alumnus who may well succeed Johnson one day, has spoken of the need for a “Big Bang 2.0.” Echoing the government’s post-Brexit “Global Britain” mantra, a Treasury spokesman says the goal is to scour the planet for opportunities and “regulate better for the U.K. market.” The Treasury is reviewing everything from stock exchange listing rules to regulation of investment funds. The goal is to put the City at the heart of new financial revolutions, including Chinese offshore renminbi trading and cryptocurrencies. The U.K. is also attempting to grab a leading share of the nascent green-finance market as banks and other institutions commit to funding projects to tackle climate change.

The U.K. accounted for more than 80% of all fintech funding in Europe in 2018. One example is Starling Bank Ltd., which has gathered deposits of £4.8 billion ($6.6 billion) since kicking off in 2014. Founder Anne Boden says the U.K.’s flexible approach to regulation was key to Starling’s success. “If anything, London will become more of a center of innovative financial services, because of its ability to come up with a new set of proportional regulation,” Boden says.

In St. Pancras station, there’s a poignant metaphor for where London—and its financial-services engine—finds itself. As many as 60 Eurostar trains used to make the journey every day to Paris and Brussels through the undersea tunnel that’s the only physical link between Britain and the continent. Today, just one daily service is left; the route’s operator is awaiting a financial lifeline to help it survive the pandemic. London’s workers were some of the Eurostar’s biggest users.

“You can’t just walk out of a marriage and become friends right away,” says Catherine McGuinness, who chairs the policy committee at the City of London Corp., the municipal government overseeing the district. “It’s going to take us a little time to reestablish trust.” —With Alex Morales, David Hellier, Silla Brush, and Viren Vaghela

©2021 Bloomberg L.P.