Boston Built a New Waterfront Just in Time for the Apocalypse

Boston Built a New Waterfront Just in Time for the Apocalypse

(Bloomberg Businessweek) -- On a balmy June morning, a gathering of local dignitaries welcomed the latest glittering jewel to Boston’s new Seaport District: a 17-story tower that will house 1,000 Massachusetts Mutual Life Insurance Co. employees. In a display of artistry and engineering, the $240 million building will have an undulating glass facade designed to reflect the harbor’s rippling waters, as if it had risen fully formed from the ocean’s depths. Massachusetts Governor Charlie Baker marveled that he’d officiated at three or four groundbreakings here in just a few weeks. “Do you get to keep all that tax revenue?” he joked with Boston Mayor Marty Walsh.

Only a decade ago, Boston’s Seaport District, located just southeast of downtown, was little more than a crazy quilt of outdoor parking lots and warehouses. Then the city began recruiting startups and big corporations to what it dubbed a new “Innovation District,” and the area sprouted offices for General Electric, Amazon.com, Vertex Pharmaceuticals, Fidelity Investments, and PricewaterhouseCoopers, as well as luxury condominiums, museums, and some of the city’s hippest restaurants.

What no one mentioned at this month’s event is Boston’s poor timing. No American city has left such a large swath of expensive new oceanfront real estate and infrastructure exposed to the worst the environment has to offer, according to Chuck Watson, owner of Enki Research, which assesses risk for insurers, investors, and governments. The expansion totals 1,000 acres, an area bigger than Manhattan’s Central Park.

Boston Harbor already floods a dozen times a year, up from two or three times in 1960, according to William Sweet, an oceanographer with the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) in Silver Spring, Md. Record high-tide floodwaters during a storm last year trapped motorists, closed a nearby subway station, and proved that Seaport dumpsters can float.

“There is a lot of hubris,” says Spencer Glendon, an economist and senior fellow at Massachusetts’ Woods Hole Research Center, which studies climate change. “There is nothing more exciting for a city government than seeing lots of tall buildings going up and going to lots of ribbon-cuttings. Everyone knows South Boston keeps flooding, and they keep building.”

Corporate executives and city officials are now scrambling to protect the Seaport. It won’t be easy: The area is a man-made peninsula that was born almost two centuries ago when workers started filling in tidal flats with rocks, dirt, and trash. Some parts were little more than a foot or two above the high-tide line. “We’re proposing infrastructure that we believe will protect the city,” says Richard McGuinness, a senior planning official working on Boston’s response to climate change. “How do you retreat from billions of dollars of assets? It’s not practical.”

Developers are elevating ground floors, putting electrical and other critical equipment on higher ones, and investing in salt water-resistant materials and flood barriers to protect garages and other vulnerable areas of buildings. Boston is planning a series of sea walls, berms, and other structures that will act like a barricade against Mother Nature. The city this month opened an elevated playground near Boston’s Children’s Museum that will double as the first such water barrier. The city still needs to raise as much as $1 billion for Seaport defenses.

Other cities are taking similar steps. New York City has raised $20 billion in public money for, among other things, sewer improvements and a Staten Island sea wall, and Mayor Bill de Blasio has said he needs at least $10 billion more for projects to protect Lower Manhattan, including extending the island up to 500 feet into the East River. In Miami, voters backed a $400 million bond issue that will help finance protections across the city. San Francisco is spending hundreds of millions of dollars to rebuild its 100-year-old sea wall.

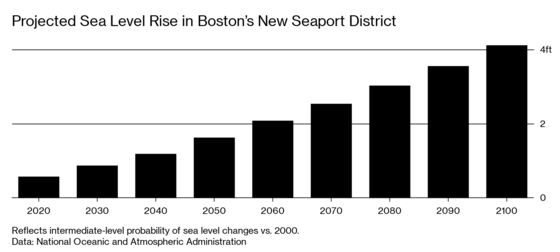

Boston is especially vulnerable to rising sea levels and the fierce storms known as nor’easters. Since 1980 it has experienced the most high-tide flooding of any city along the East Coast, according to NOAA’s Sweet. By the end of the century, Boston Harbor could be 2 to 4 feet higher than it is now.

To prepare for the watery onslaught, WS Development, the Seaport’s biggest developer, is building up the ground beneath its projects. The Massachusetts company is juggling $3 billion in projects—7.6 million square feet of hotels, stores, restaurants, and offices, including a tower for 2,000 Amazon.com Inc. employees.

At the $360 million St. Regis condo tower, now under construction, flood walls will rise from the ground to block waters. Also, its lobby floor has been designed so it can be permanently raised by four feet as flooding worsens, according to developer Jon Cronin. He’s hopeful that his neighbors and the city will follow suit. “We don’t want to be the only building in the middle of an island,” he says.

The new MassMutual building, which will be completed in 2021, will be equipped with so-called aqua fences, portable water barriers that can be assembled in a matter of hours. Roger Crandall, MassMutual’s chief executive officer, says other countries have been able to protect themselves from the ocean. Why not Boston? “Our species has been engineering against the seas for a long time,” says Crandall, noting that he’d recently visited the Netherlands. “There’s a cost to it—make no mistake—but there’s also a cost of picking up and moving development further inland.”

To contact the editor responsible for this story: John Hechinger at jhechinger@bloomberg.net, Cristina Lindblad

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.